Justice Gorsuch is just over two months into his tenure on the Supreme Court. There are many unknowns regarding how he will judge at this level. The cases he will decide on the Supreme Court are predominately different from those he saw on the 10th Circuit. There is also an intuition that circuit court judges’ decisions are shaped by whether they aspire to sit on the Supreme Court. This may add to the unreliability of Justice Gorsuch’s work on the 10th Circuit as a predictor for his Supreme Court decision-making. After his first three opinions – one majority, one dissent, and one concurrence – several predictions about Gorsuch have been tentatively confirmed. Other suppositions will be confirmed or denied in the coming weeks and during the Court’s next term.

What We Know

Justice Gorsuch’s three opinions were the majority opinion in Henson v. Santander, a concurrence to Justice Kagan’s majority opinion in Maslenjak v. United States, and a dissent from Justice Ginsburg’s majority opinion in Perry v. Merits Systems. The two main predicted features of Justice Gorsuch that have so far been tentatively confirmed are where he lines up ideologically on the Court and how he will interpret the law.

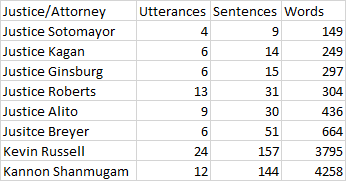

At first blush it may be surprising that Justice Gorsuch wrote the majority opinion in Henson as he didn’t say a word during that oral argument. The speech statistics for the Henson oral argument can be found below:

Although the oral arguments did not give away that Justice Gorsuch would write the majority opinion, this was a straightforward statutory interpretation case, which many (including myself) assumed would be Justice Gorsuch’s bread-and-butter on the Court. He did not disappoint on this front with his textualist approach to interpretation in the opinion affirming the 4th Circuit’s decision. Whether by referring to the statutory text

- “we begin, as we must, with a careful examination of the statutory text”;

- “And by its plain terms this language seems to focus our attention on third party collection agents working for a debt owner—not on a debt owner seeking to collect debts for itself;

- “ Neither does this language appear to suggest that we should care how a debt owner came to be a debt owner—whether the owner originated the debt or came by it only through a later purchase.”)

or English language rules

- “But this much doesn’t follow even as a matter of good grammar, let alone ordinary meaning”;

- “The Cambridge Guide to English Usage 409 (2004) (explaining that the term ‘past participle’ is a ‘misnomer[ ], since’ it “can occur in what is technically a present . . . tense’)”;

- “As a matter of ordinary English, the word “obtained” can (and often does) refer to taking possession of a piece of property without also taking ownership—so, for example, you might obtain a rental car or a hotel room or an apartment. See, e.g., 10 Oxford English Dictionary 669 (2d ed. 1989)”

Justice Gorsuch points to how the statute’s language leads to the Court’s decision. Accordingly, Justice Gorsuch conveys towards the end of the opinion, “it is never our job to rewrite a constitutionally valid statutory text under the banner of speculation about what Congress might have done had it faced a question that, on everyone’s account, it never faced.”

While not one of the more talkative justices during Maslenjak’s oral arguments, Justice Gorsuch did contribute with a little more to say to the petitioner’s attorney than to the respondent’s. Justice Gorsuch spoke 342 words over the course of the oral argument. The following two graphs break down the points at which Justice Gorsuch spoke during the petitioner’s and respondent’s arguments.

Gorsuch’s concurrence espouses an approach steeped in judicial restraint as he says,

“For my part, I believe it is work enough for the day to recognize that the statute requires some proof of causation, that the jury instructions here did not, and to allow the parties and courts of appeals to take it from there as they usually do.”

Justice Gorsuch’s narrow approach would not have reached the question of causation which is discussed in the majority opinion: “But the question presented and the briefing before us focused primarily on whether the statute contains a materiality element, not on the contours of a causation requirement.” In this opinion Gorsuch provides a textualist lens to his statutory analysis as well: “The Court holds that the plain text and structure of the statute before us require the Government to prove causation as an element of conviction.”

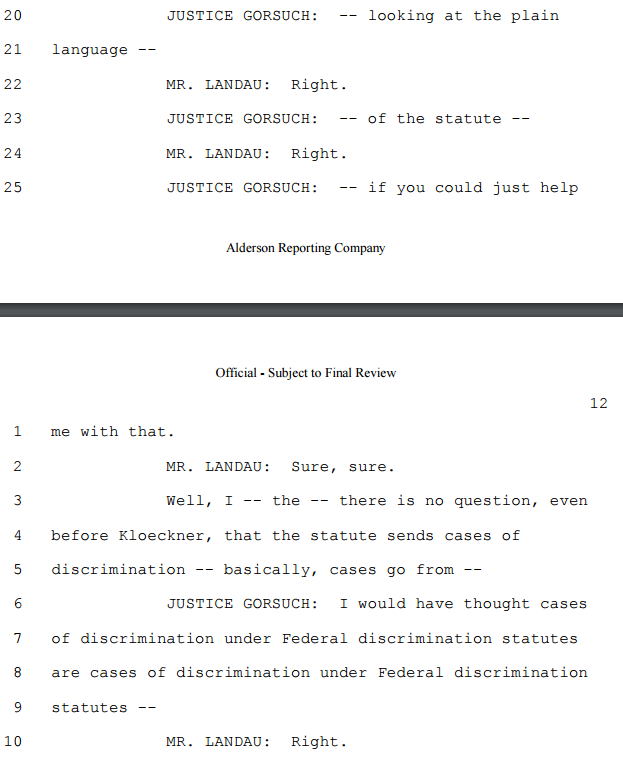

Gorsuch spoke much more during the Perry oral arguments than he did during any other arguments this term. His comments were just about equally directed towards the petitioner’s and respondent’s attorneys. In the oral arguments, Justice Gorsuch hinted that he thought the statute’s plain language did not accord with the petitioner’s argument (Justice Gorsuch would have affirmed the lower court’s decision in the case).

In his dissent to Justice Ginsburg’s majority opinion in the case, Justice Gorsuch first describes the clarity of the statutory language, “[t]hese rules provide straightforward direction to courts and guidance to federal employees who often proceed pro se.” He also explains how in his opinion the respondent’s approach leads to a rewriting of the statute:

“Mr. Perry’s is an invitation I would run from fast. If a statute needs repair, there’s a constitutionally prescribed way to do it. It’s called legislation. To be sure, the demands of bicameralism and presentment are real and the process can be protracted. But the difficulty of making new laws isn’t some bug in the constitutional design: it’s the point of the design, the better to preserve liberty. Besides, the law of unintended consequences being what it is, judicial tinkering with legislation is sure only to invite trouble.”

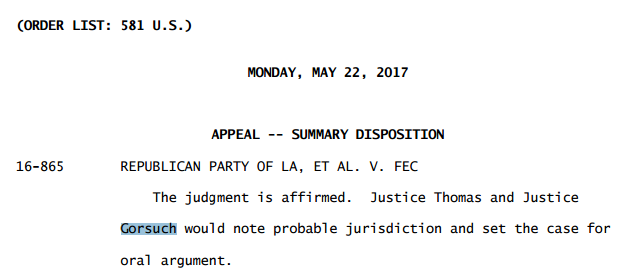

The confirmations of Justice Gorsuch’s decision making that we find from these cases include primarily his textualist approach to statutory interpretation which is evident in all three opinions. We also see where he may fall ideologically on the Court. He has been most often tied to Justice Thomas, the most conservative Justice on the current Court. In Justice Gorsuch’s first public decision on the bench he and Justice Thomas declared they would have noted probable jurisdiction in a campaign finance case that was summarily affirmed.

Justice Thomas was the only Justice to join Justice Gorsuch’s dissent in Perry and the only Justice to join his concurrence in Maslenjak. In the one 5-4 decision so far this term, McWilliams v. Dunn, Justice Gorsuch joined the other members of the conservative wing of the Court – Justices Roberts, Alito, and Thomas – in dissent. Justice Gorsuch’s alignment with Justice Thomas was perhaps a somewhat foregone conclusion given the similarities in their interpretive styles. Justice Gorusch’s only separate opinions were written in response to majority opinions by the (likely) more liberal Justices Kagan and Ginsburg. Whether Justice Gorsuch will fill Justice Scalia’s shoes as another regular conservative vote in closely split decisions is unclear although the available evidence points towards that likelihood.

What We Should Expect

Taking a step back there is much to be gained from looking at the beginning of other justices’ work on the Supreme Court. Since many comparisons have already been drawn between Justice Gorsuch and Justices Thomas and Scalia, these are the focal justices for comparison.

Justice Scalia’s first decision in O’Connor v. United States dealing with taxation also utilized a textualist approach. This is apparent in several instances:

- “There is some purely textual evidence, albeit subtle, of the understanding that Article XV applies only to Panamanian taxes”

- “More persuasive than the textual evidence, and in our view overwhelmingly convincing, is the contextual case for limiting Article XV to Panamanian taxes. Unless one posits the ellipsis of failing to repeat, in each section, § 1’s limitation to taxes “in the Republic of Panama,” the Article takes on a meaning that is utterly implausible and has no foundation in the negotiations leading to the Agreement.”

- “In sum, we find the verbal distortions necessary to give plausible content, under the petitioners’ theory, to the second sentence of § 2 and § 3 far less tolerable than the acknowledgment of ellipsis which forms the basis of the Government’s interpretation.”

Several of Justice Scalia’s other early opinions dealt with First Amendment issues. He stated he would have heard full arguments in the case City of Newport, Kentucky v. Iacobucci, dba Talk of the Town, dealing with nude dancing establishments, which was summarily decided by the Court without argument.

Justice Scalia’s first dissent from a signed opinion was in Tashjian v. Republican Party of Connecticut. His dissent in this case dealing with election law was joined by Justices Rehnquist and O’Connor. In important part, Justice Scalia writes,

“Both the right of free political association and the State’s authority to establish arrangements that assure fair and effective party participation in the election process are essential to democratic government.”

Justice Thomas had a smattering of case types while in his first term on the Supreme Court. His first majority opinion was in Molzof v. United States dealing with punitive damages. His decision goes directly to the statutory text –

“We agree with petitioner’s interpretation of the term “punitive damages,” and conclude that the Government’s reading of § 2674 is contrary to the statutory language. Section 2674 prohibits awards of “punitive damages,” not “damages awards that may have a punitive effect.”

In this opinion he also thoroughly explicates an approach to statutory construction he espouses describing,

A cardinal rule of statutory construction holds that:

“[W]here Congress borrows terms of art in which are accumulated the legal tradition and meaning of centuries of practice, it presumably knows and adopts the cluster of ideas that were attached to each borrowed word in the body of learning from which it was taken and the meaning its use will convey to the judicial mind unless otherwise instructed. In such case, absence of contrary direction may be taken as satisfaction with widely accepted definitions, not as a departure from them.” Morissette v. United States, 342 U. S. 246, 263 (1952).

This case was decided unanimously. Thomas first concurrence in White v. Illinois was joined alone by Justice Scalia and his first dissent from a signed opinion in the original jurisdiction case Wyoming v. Oklahoma was joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Scalia. Like Justice Gorsuch’s concurrence in Maslenjak, this dissent also alluded to the importance of an interpretive approach guided by judicial restraint:

“It has long been this Court’s philosophy that ‘our original jurisdiction should be invoked sparingly.'” Illinois v. City of Milwaukee, 406 U.S. 91, 93, 31 L. Ed. 2d 712, 92 S. Ct. 1385 (1972) (quoting Utah v. United States, 394 U.S. 89, 95, 22 L. Ed. 2d 99, 89 S. Ct. 761 (1969)). The sound reasons for this approach have been set forth on many occasions, see, e. g., Ohio v. Wyandotte Chemicals Corp., supra, at 498; Maryland v. Louisiana, supra, at 761-763 (REHNQUIST, J., dissenting), and I need not repeat them here.”

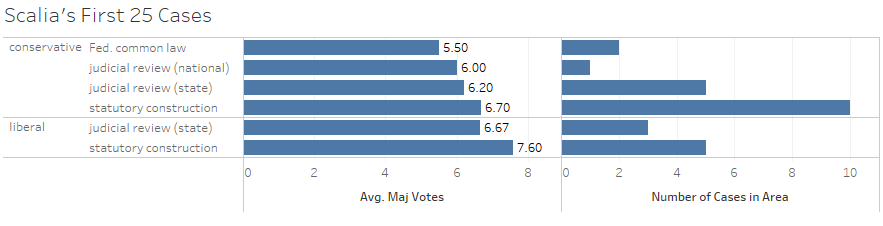

The interpretive approach and coalitions reached by Justices Scalia and Thomas during their early days on the Court are of a similar type to what we have seen so far from Justice Gorsuch. It would not be far-fetched to imagine that Justice Gorsuch will continue on a similar trajectory. What might this look like? Fortunately, we have data on Justices Scalia and Thomas. The following figures chart these justices first twenty-five majority decisions looking at the ideological direction of their rulings, the decisional authority, and the majority votes averaged when they wrote decisions in each of these buckets (data supplied by the Supreme Court Database).

Perhaps surprisingly, eight of Justice Scalia’s first twenty-five decisions skewed liberally. He actually had the most support on average when he authored liberal decisions based around statutory construction. He had the least support when he authored conservative decisions based on federal common law. Finally the bulk of Justice Scalia’s first twenty-five decisions were conservatively decided and based on statutory construction.

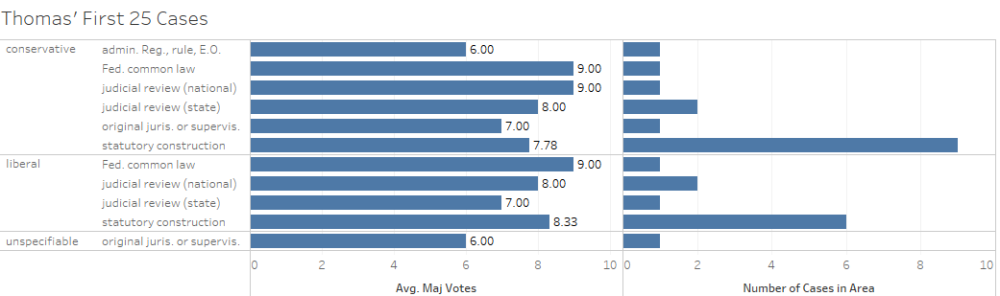

Justice Thomas had two more liberal decisions in his first twenty-five (with ten) than Justice Scalia did in his. Like Justice Scalia, Justice Thomas decided more cases conservatively and based on statutory construction than any other type. He received strong support in his first twenty-five decisions as none of the decision permutations received less than an average of six majority votes. As mentioned above Justice Thomas had a more diverse set of cases early in his Supreme Court career with cases based on administrative regulations, national judicial review, and on original jurisdiction.

These comparisons provide a vision of what we might expect for Justice Gorsuch’s next set of decisions on the Court. Based on Justice Scalia’s and Justice Thomas’ examples we may see Justice Gorsuch strengthen the coalitions he has already participated in and continue to make narrow decisions based predominately on his readings of the plain text of statutes.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

So unfortunate that the newest justice feels compelled to sprinkle contractions throughout his opinions. Legalese is certainly not required and should be avoided. But this predilection turns what is supposed to be authoritative into what reads like a blog post.

LikeLike