All Article III federal judgeships start at the same place — with a presidential nomination. This procedure played a large role in the first several decades of statistical studies of judicial behavior, where researchers found that the party of appointing president was a strong predictor of judicial votes. While not looked at as frequently anymore, the party of appointing president still yields interesting questions. For instance, are the Supreme Court Justices votes predictable, at least to some extent, because there are clear and correct solutions to cases? Are differences in the justices’ votes due to differing interpretations of doctrine, divergent preferences, or some other combination of factors?

Even though the justices are all well educated experts in the field, they frequently diverge in their votes as the justices tend to divide in their positions more than 50% of the time each term. This also means that a fair number of decisions each term are unanimous, which should not be understated. One of the goals of this post is to understand why the justices divide in their votes and to what extent this divergence is based on political factors.

The public now often views the Court as making decisions at least in part based on partisan motives. How do we test whether this is an accurate assessment? One way is to look at how the justices treat cases coming from lower courts. The current Court is one of the first where the more conservative justices were all nominated by Republican presidents and vice-versa for liberals. We might then expect justices nominated by Democrats to agree with the positions of Democratic judges below and for a similar relationship between Republican judges and justices. The data in this post looks at decisions from the past three terms (2020-2022) and focuses on the justices votes and how they relate the panel composition below. The Supreme Court Database was used for coding the direction of the justices’ votes. Most importantly, it looks at whether party (of appointing president) alignment leads to more agreement and consequently whether differences in party of appointing presidents lead to opposing positions in the same cases.

The analysis in this post looks at correlates for the justices votes. The specific groupings look at:

- Whether the majority party in lower court panel compositions matters,

- To what extent do the justices align their individual votes with those of judges from the same party of appointing president below, and

- Whether the justices vote more frequently for Trump appointees than they do for other Republican appointees in the lower courts, and

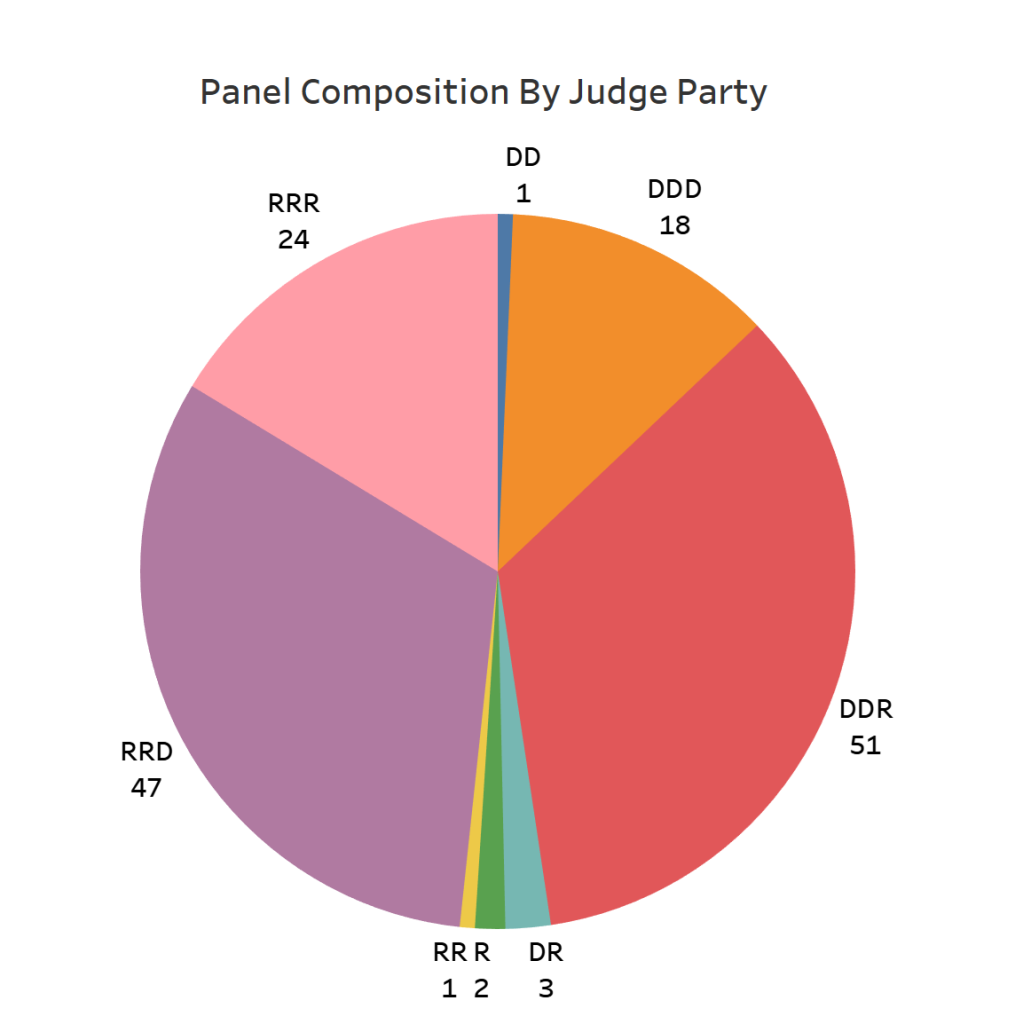

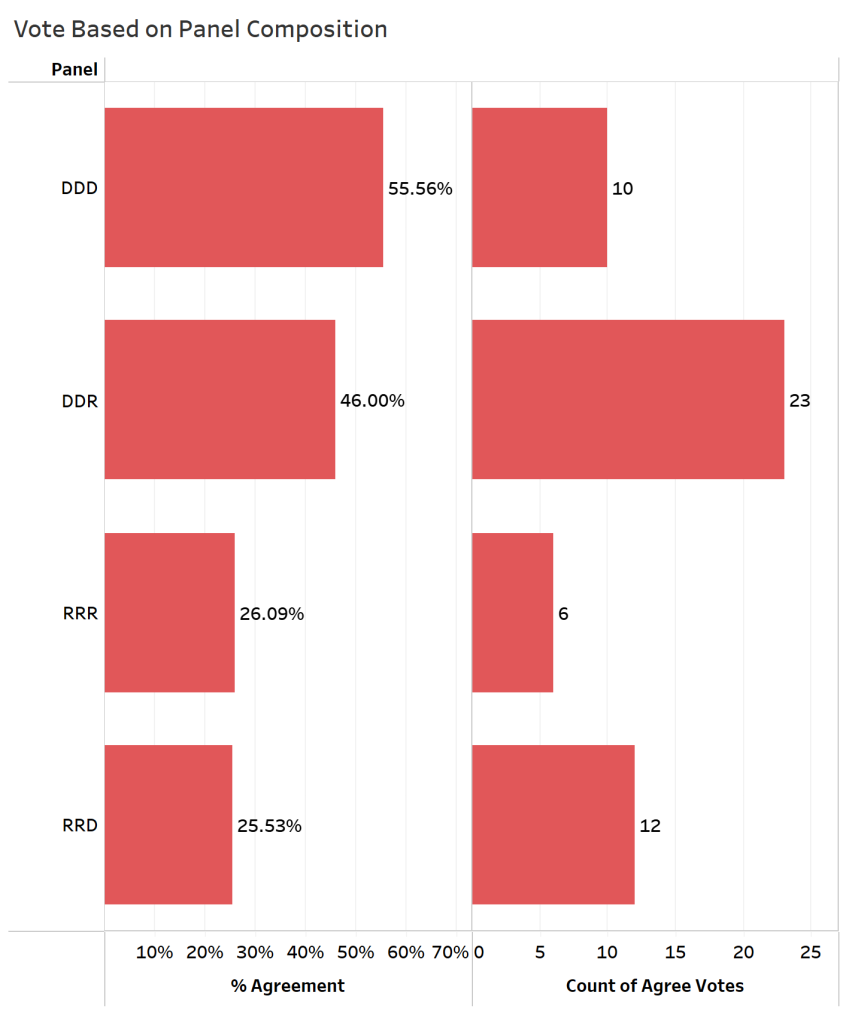

The lower courts for the purposes of this post are the federal courts of appeal and so cases from other lower courts were excluded from this analysis. The lower court decisions that the Court reviewed in the Supreme Court were based a review of Westlaw’s case history and SCOTUSBlog’s links to lower court opinions on its case profiles (please note that for en banc decisions, only the authoring justices’ positions were coded). While the vast majority of the decisions below were from three judge panels there were a few instances with two judge panels or single justice orders. The appointing party makeup of the panels below were as follows (“D” for Democrat and “R” for Republican):

For three judge panels, the largest number were made up of two Democratic and one Republican appointee (51) followed by two Republicans and one Democrat (47). For panels composed of appointees all from a single party though, there were more constituted by all Republicans (24) than all Democrats (18).

With the panels laid out we next get to measurement. The first is alignment of interest is between the justices and lower court judges. Observations in these instances consist of determining if the justice votes to affirm votes by judges appointed by presidents of the same party. Thus, we might expect justices appointed by Republican presidents to affirm all Republican appointed panels more frequently and vice-versa for Democratic appointees.

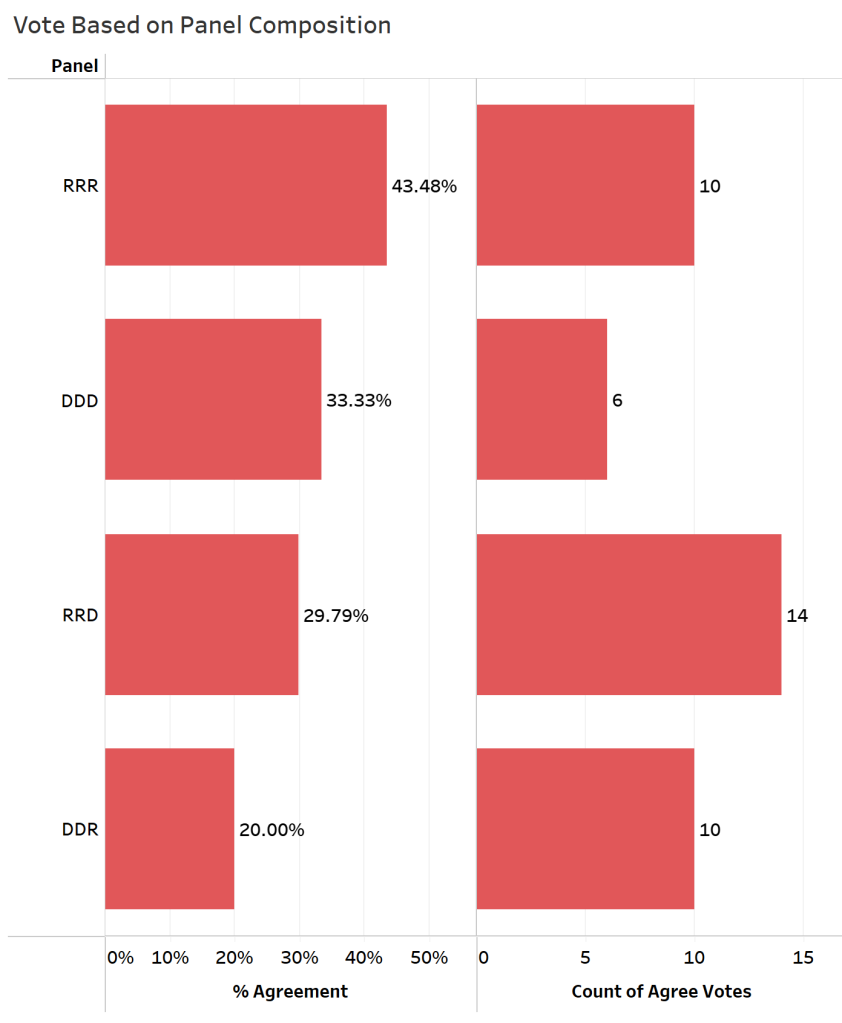

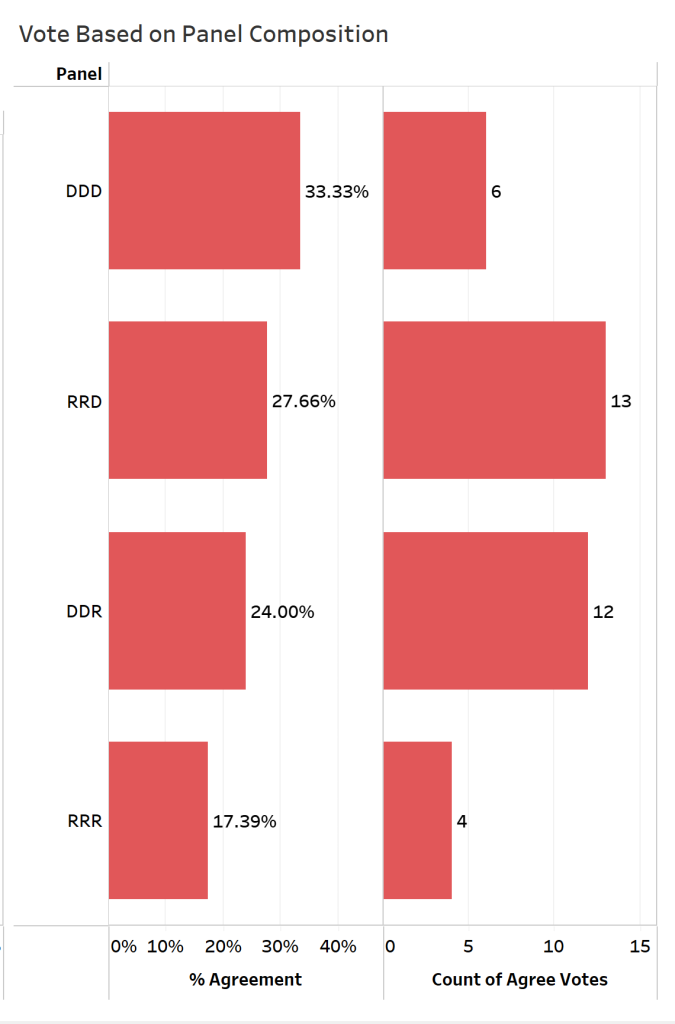

Case selection, however, might throw off these hypotheses. The Court has almost unlimited control over the cases it hears and since the justices most often vote to reverse lower court decisions, the party of appointing president effect might be diminished due to choices of cases to hear. Below are graphs for each justice between the 2020/2021 and 2022/2023 Terms that look at affirming votes based on panel composition. There are two exceptions to the inclusion of justices though. The first is that there are no analyses for Justice Breyer since he isn’t a current justice even though he was on the Court for two of those three terms. The second is that since Justice Jackson only sat for one of these three terms, her results are given in absolute numbers rather than in percentages as is the case with the rest of the justices.

Republican Appointees (in order of date of confirmation)

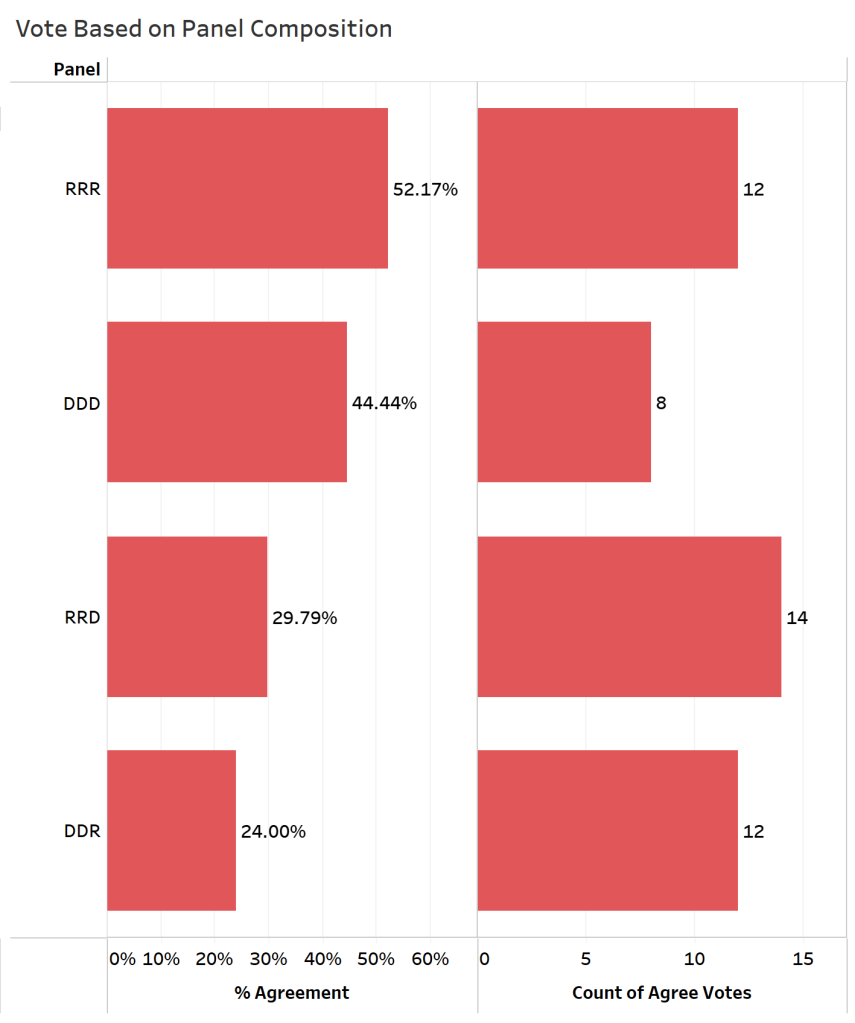

Thomas

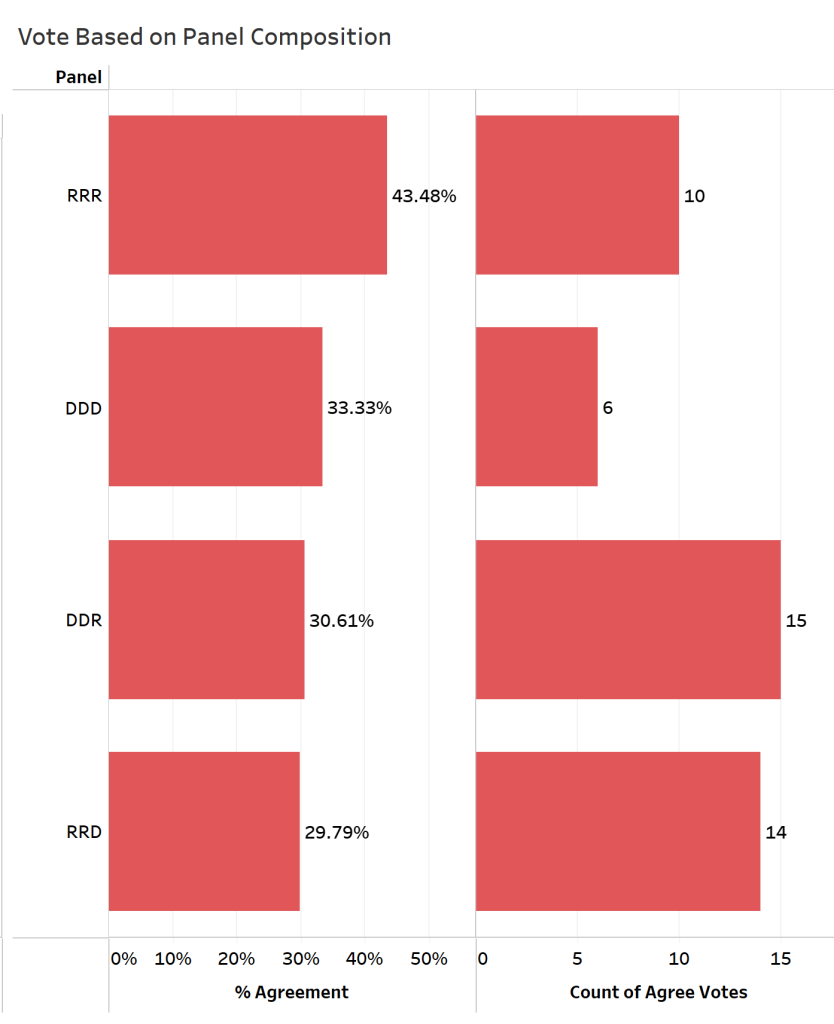

Roberts

Alito

Gorsuch

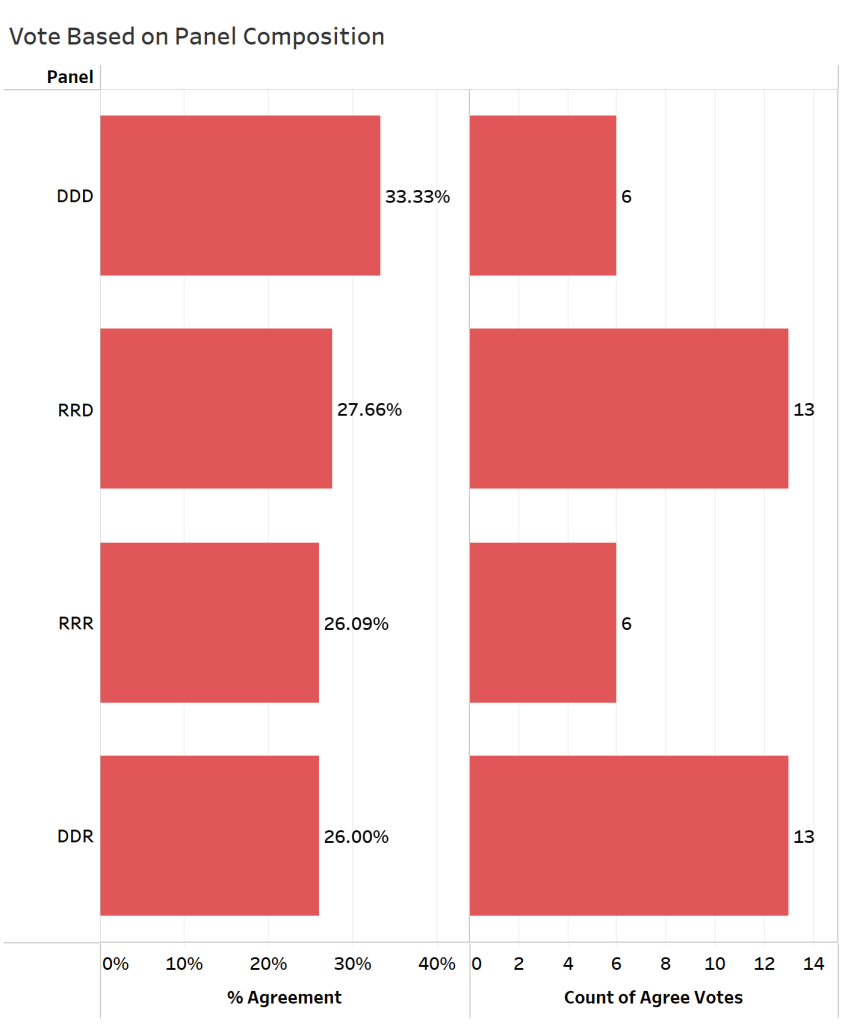

Kavanaugh

Barrett

All of the Republican appointees voted to affirm decisions from panels consisting of all judges appointed by presidents from one party most frequently. Four of the justice affirmed all Republican panels most frequently while two, Roberts and Kavanaugh, voted to affirm decisions of all Democrat panels most frequently. Thomas was the only justice to affirm any panel composition more than 50% of the time (he affirmed decisions from all Republican panels 52% of the time). Kavanaugh’s rate of affirming decisions from all Republican panels was the lowest for any of the Republican nominated justices for any panel composition at just over 17% of the time.

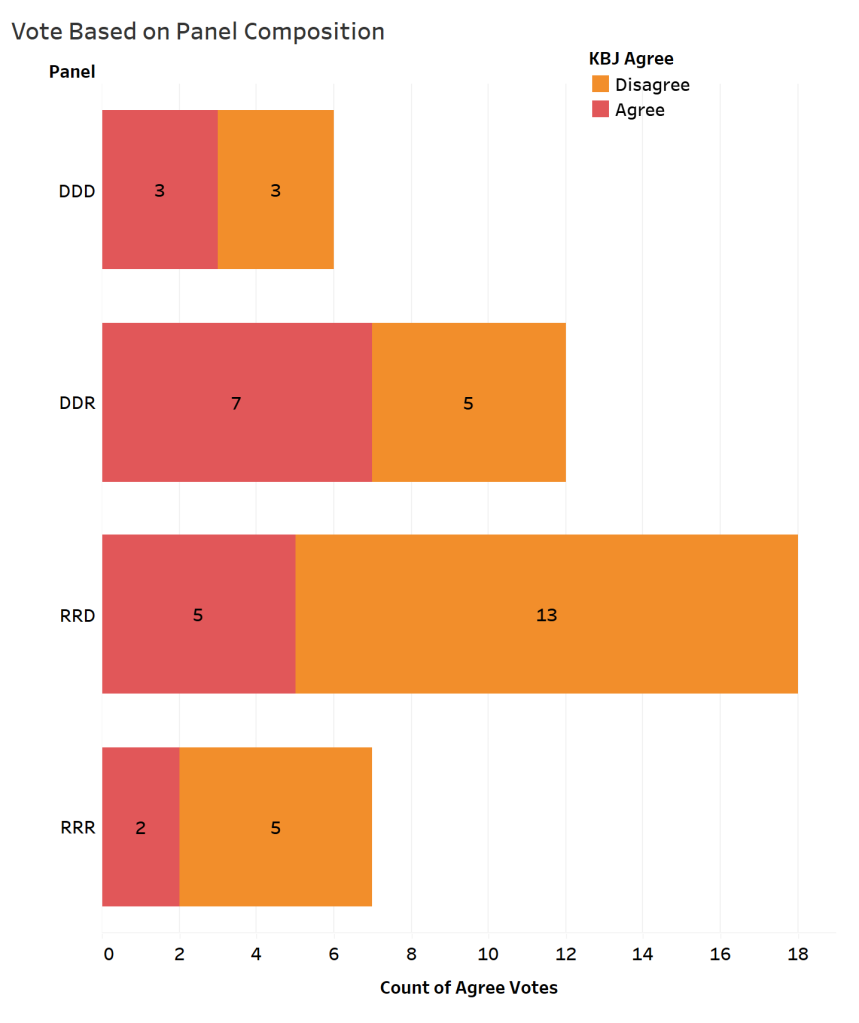

Democratic Appointees (in order of date of confirmation)

Sotomayor

Kagan

Jackson

The Democratic appointees were more consistent across the board in their orders of affirmance preference based on lower court judge panel composition. Sotomayor and Kagan both affirmed all Democratic panels most frequently at a rate of over 50% and affirmed panels with two Democratic appointees and one Republican next most often. Jackson affirmed panels with two Democratic appointees and one Republican most frequently and then panels with all the Democratic appointees.

These graphs show the justices’ propensities to align their votes with judges appointed by presidents of the same party although Roberts and Kavanaugh show that there are some exceptions to this rule. Still, the party alignment effect seems prevalent across the justices, especially as you reach the edges of the ideological spectrum.

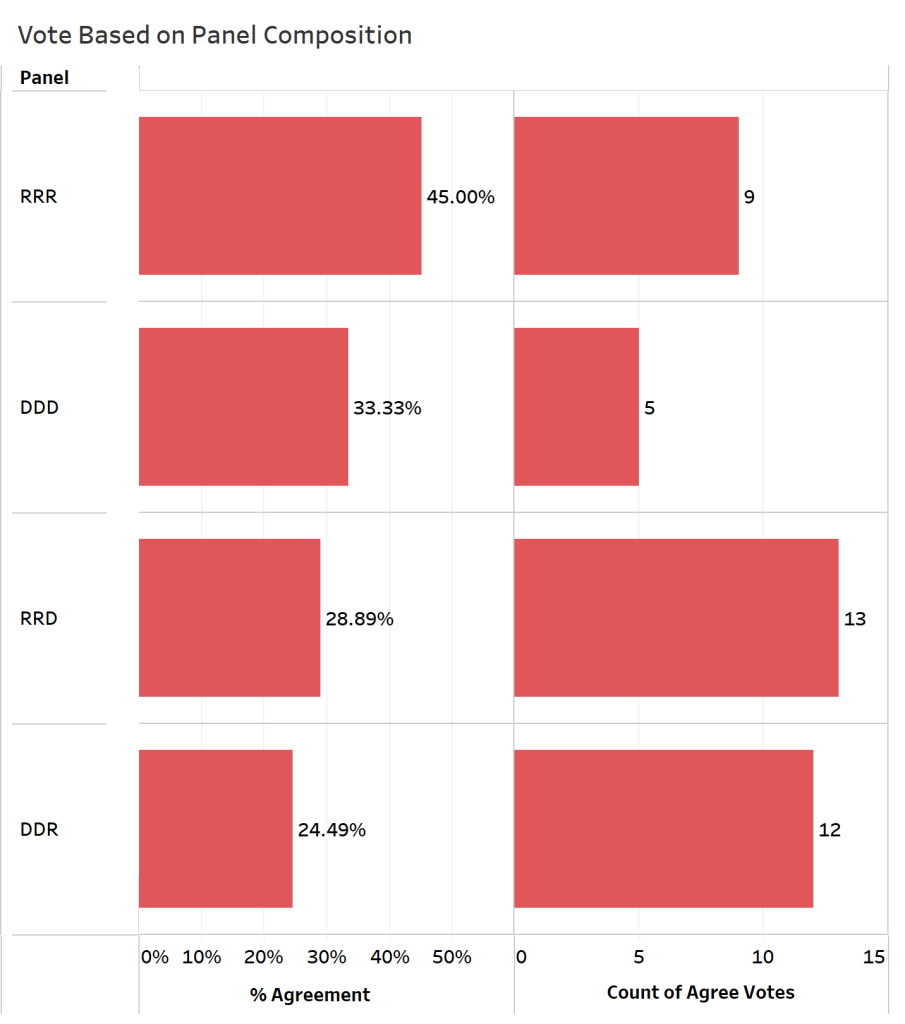

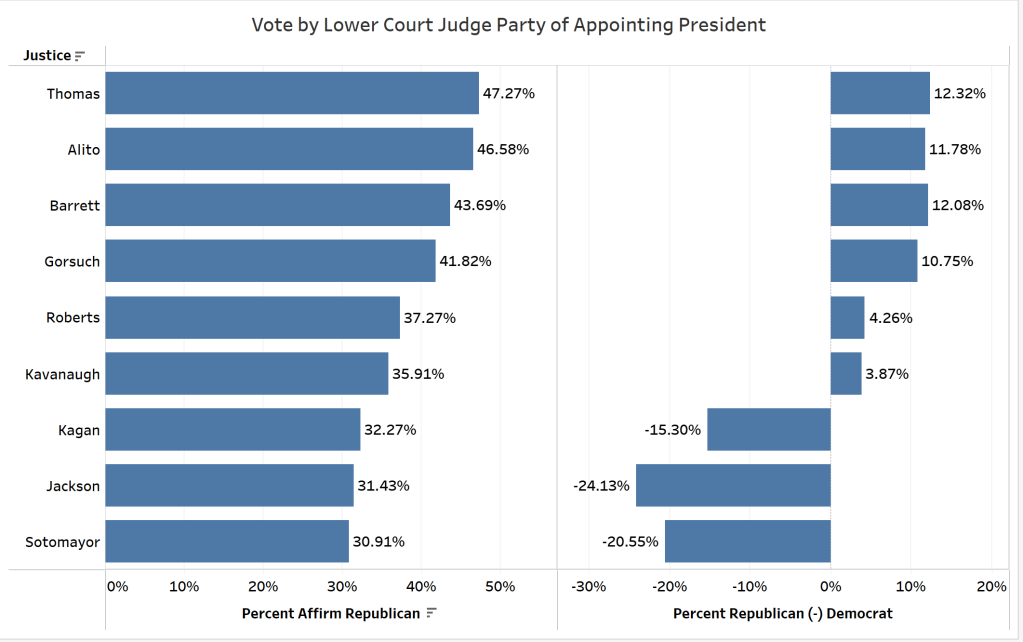

The next two graphs are comparative and inclusive of all current justices. The first looks at the justices based on their order of alignment with votes of Republican appointed judges below. To construct this measure, I looked at whether the judge’s vote was in majority or dissent, whether the justice’s vote was in majority or in dissent, and if the Court’s decision was to affirm or reverse the decision of the lower court. The second part of this graph looks at the differential in the justices’ rates of aligning in their votes with Republican judges and Democratic judges.

The party of appointing president alignment is clear in this graph. All of the Court’s Republican appointees aligned with Republican judges below more frequently than the Democratic appointed judges (left side). All six Republican appointees also sided with votes from Republican judges below more frequently than with Democratic appointees (right side).

Justice Thomas who voted to affirm all Republican panels most often also aligned his votes with Republican appointees below most frequently. This led Thomas to have the greatest difference in preference in favor of Republican over Democratic appointees below.

The biggest differences though were for the Court’s Democratic appointees. Along with aligning their votes least often with Republican appointed judges below, these justices’ rate differentials in favor of Democratic appointees were all greater than the Republican appointees’ rates of aligning with Republican judges below.

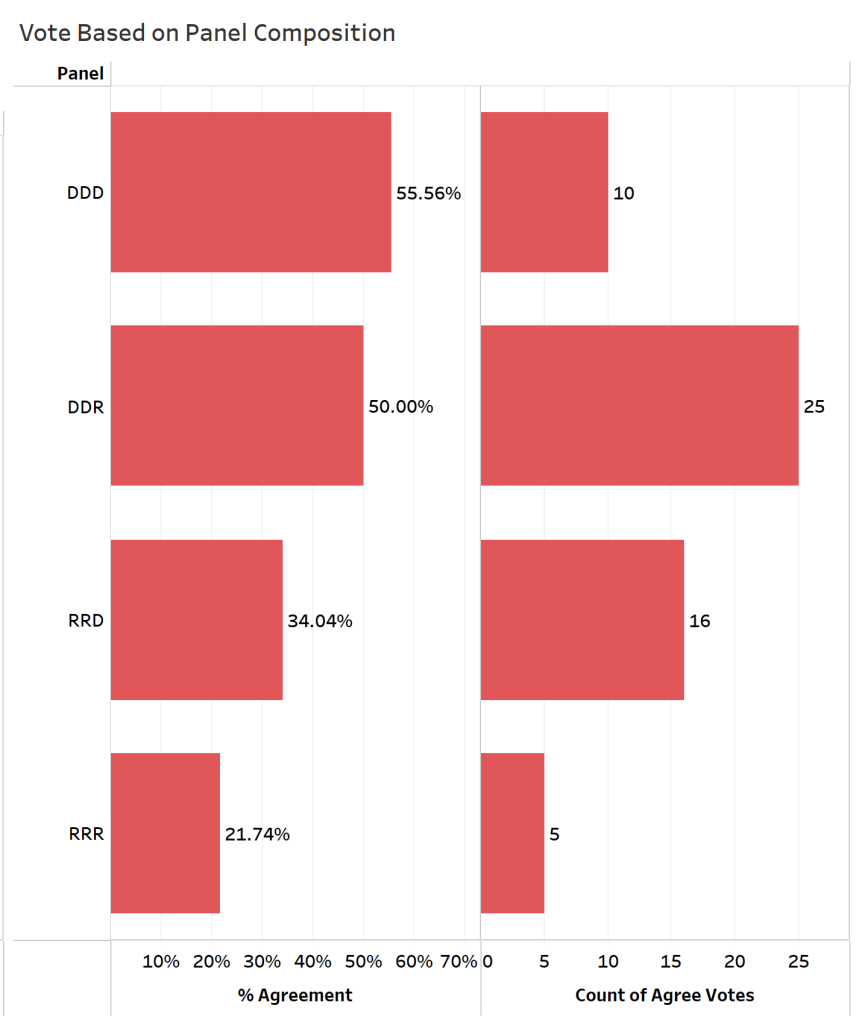

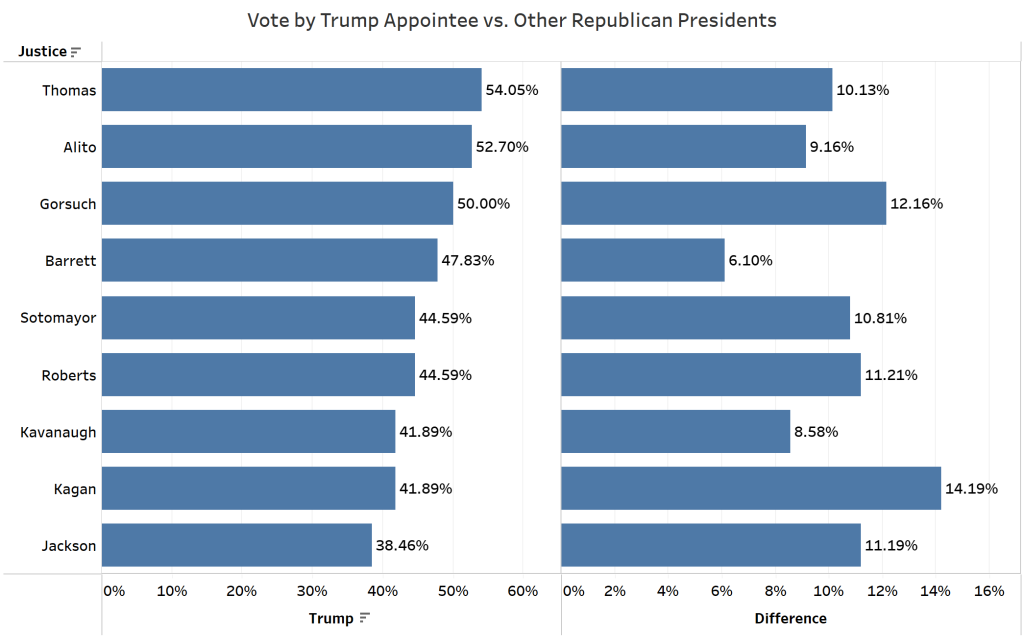

The next graph looks at the frequency with which the justices’ votes align with votes by Trump appointees below compared to votes from other Republican appointees. If Trump pushed the pendulum in the appeals courts more in the conservative direction, then we may expect stronger support for Trump’s appointed judges from of the Court’s Republican appointees than from the Democratic appointees. Generating expectations for this vote correlation though is more complex than for splitting based on party alone as it depends on our expectations for and perspectives of commonalities between Trump appointees.

Most notable at the outset we see on the right that all of the justices’ votes align with Trump nominees more frequently than with other Republican appointed judges. While the order in rates mainly shows the Court’s Republican appointees aligning with Trump’s judges more often than the Democratic appointees, this was not the case across the board. In fact, one of the Trump’s appointees to the Court, Justice Kavanaugh, actually sided with Trump judges in the appeals courts less often than all of the other Republican appointees on the Court and less frequently than a Democratic appointee, Justice Sotomayor. Justice Roberts’ rate of alignment with Trump judges was also below that for Justice Sotomayor.

The differences in support for Trump appointed judges and judges appointed by other Republican presidents were quite interesting as well. The two smallest differences were from two of Trump’s appointees to the Court – Justice Kavanaugh (8.58%) and Justice Barrett (6.10%).

At the end of the day, we see the justices are predictable in some ways and surprising in others. Most of the justices vote in expected ways depending on lower court panel composition, but Justices Roberts and Kavanaugh were more supportive of positions of Democratic appointees below than some might have anticipated. This difference held true when the data was broken down more granularly based on judges rather than overall panel composition. The finding for the justices votes when Trump’s appointees were isolated shows that even the Court’s Democratic appointees shared more positions with these judges than with other Republican appointees below. While there was not a clear hypothesis for how the justices might have voted in those instances, if we assume that Trump moved the federal appeals courts in a more conservative direction, then this unanimous difference in support is somewhat unexpected as well.

Find Adam on X/Twitter and LinkedIn. He’s also on Threads @dradamfeldman and on Bluesky Social @dradamfeldman.bksy.social