In 1980, a young John Roberts began a clerkship with Chief Justice William Rehnquist. Former colleagues recalled him as “meticulous” and “brilliantly efficient,” and The New York Times later observed that Roberts “stood out for conservative rigor,” his memoranda concise, procedural, and laced with the dry wit that has since defined his judicial writing. That apprenticeship was more than a line on a résumé; it was a proving ground, one that foreshadowed the cautious institutionalism Roberts would carry into his role as Chief Justice decades later.

Roberts’s story is not unique. Clerking at the Supreme Court has long been described as the profession’s golden ticket. As the Supreme Court Historical Society notes, clerks are “an extension of the Justices themselves,” drafting memos, reviewing petitions, and shaping the very language of opinions. Their influence lingers long after they leave One First Street: they become federal judges, deans, cabinet officials, and, in Roberts’s case, Chief Justice himself. As Harvard’s Martha Minow has explained, “Probably more important than their influence during the one year as a clerk at the Court, a former clerk has access to knowledge, mores, strategies and ambition that can lead to outsized influence as their careers develop.”

The world of clerks is also extraordinarily exclusive. A Columbia Law Review Forum study was blunt: “Some are more equal than others,” observing that most clerks come from a narrow set of law schools and feeder judges. As CNN has reported, even the clerks’ personal dynamics can reflect broader ideological divides. In the 2002–2003 term, liberal and conservative clerks stopped eating lunch together; even a charity Jell-O-eating contest became politically fraught. Twenty years later, those same clerks are shaping America’s most consequential legal battles: Adam Mortara argued the case that ended affirmative action, Jonathan Mitchell engineered Texas’s SB 8 abortion law, and Eric Olson litigated whether Donald Trump could appear on the 2024 ballot.

That path to influence is why firms now offer Supreme Court clerks signing bonuses of nearly half a million dollars, exceeding a Justice’s annual salary. A 2020 New York Times investigation described these payouts as “money well spent,” since firms and clients prize the insider knowledge clerks bring. As one former clerk told Chambers Associate, “You’re not just carrying papers. You’re in the room when doctrine is shaped.”

This article draws on a new dataset covering 2005 to 2025 to chart the changing architecture of this elite pipeline. It traces the flow of clerks through three stages: from law schools, through feeder judges, and ultimately into the chambers of Supreme Court Justices. The data confirm the persistence of elite networks — Yale and Harvard still dominate, and a small group of appellate judges remain crucial feeders. But they also reveal change: Chicago and Notre Dame are rising, Columbia and Georgetown lag, and district court judges in Washington and New York are becoming feeders for the first time. Just as importantly, with the Court now firmly conservative, ideological alignment shapes clerk hiring more than ever, with cross-party hires almost nonexistent in some chambers.

What follows is both a map of continuity and a story of evolution — an attempt to capture how America’s most powerful legal apprenticeship has changed in subtle but significant ways over the last two decades.

The Data

Law School Placement Rates

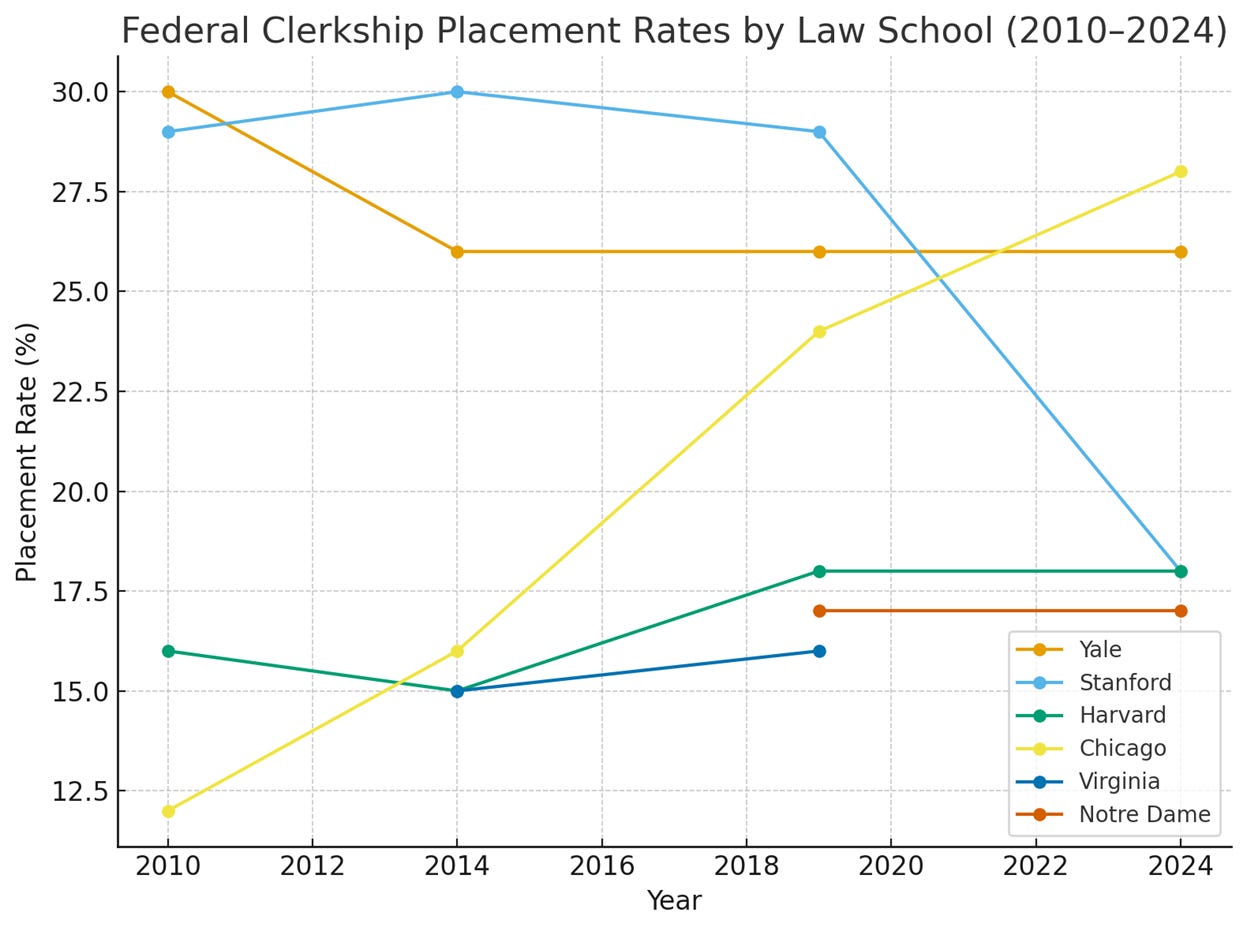

The line chart of clerkship placement rates from 2010 to 2024 captures the broad contours of the market. Yale and Stanford hover near the top throughout, with steady rates between twenty-five and thirty percent. Harvard sits lower, in the fifteen to eighteen percent range, a reminder that its enormous class size dilutes even a strong absolute record. Chicago, however, is the outlier: starting at just twelve percent in 2010, its line rises steeply year after year, reaching twenty-eight percent by 2024—nearly indistinguishable from Yale. Notre Dame’s trajectory is even more surprising, absent in 2010 but breaking into the leader board by 2019 and 2024 with a rate of seventeen percent.

Yet the lines do not just show rank; they signal institutional strategy. Yale’s and Stanford’s stability reflects long-standing clerkship cultures, where students are groomed from the outset for federal clerkships. Harvard’s flatter line suggests it produces so many graduates that even excellent placement looks modest on a percentage basis. Chicago’s sharp ascent is not an accident: it reflects deliberate investments in faculty mentoring, clerkship directors, and strong ties to feeder judges like William Pryor. Notre Dame’s appearance on the chart reveals something similar: targeted placement efforts, especially toward conservative feeder judges, have made a small school newly visible on the national stage.

In other words, the chart is not only about winners and losers—it reveals which schools treat clerkship placement as a core institutional project, and which rely more on reputation alone.

Supreme Court Clerks by School

Across 2005–2025, Yale and Harvard tower above the field

Read more on Legalytics with a paid account.

FYI, Rehnquist was not Chief Justice when Robert’s clerked for him. Rehnquist was an Associate Justice

LikeLike

Right. It was before he became Chief. The sentence could have said “(then associate Justice).”

LikeLike