The Supreme Court is in the midst of a critical juncture. For perhaps the first time since FDR was President, there is serious discussion regarding how many justices should sit on the Supreme Court. Roosevelt tried and failed to add as many as six more seats to the Supreme Court in 1937. The last time legislation passed to change the number of seats on the Court (when the Court became a nine-member body) was in 1869 with the Judiciary Act of that year. Prior to 1869, Congress changed the size of the Supreme Court several times (includes a brief stint with ten justices). In a federal system of checks and balances not only does Congress have this power to change the Court’s size, but this power is undisputed. The power in question is whether the Senate can forgo its right to nominate a new justice indefinitely after a vacancy (there is little to contradict the legality of this proposition). Highly regarded Republican Senators such as John McCain and Ted Cruz proposed leaving the seat vacant indefinitely if Clinton wins the election. Democratic Senators such as Harry Reid and Vice-Presidential candidate Tim Kaine promise to use the “nuclear option” to change the Senate voting rule if the prolonged vacancy persists without a vote.

A few things are clear. This is the longest period of time with a vacancy without a Senate hearing or vote on a nominee. Granted, this is not the longest period with a vacancy; not by a long shot. The key difference in these longer vacancies was, however, that the political process was followed as the Senate voted on nominees. While many believe that an odd number of justices is an essential element of Supreme Court composition, some (including at least one current justice) have suggested that an eight member Court is not that bad.

I recently weighed in on this discussion by looking at the costs and benefits of eight and nine member Courts in an essay for the University of Pennsylvania Law Review Online. I build on that discussion in this post. There is an often overlooked history of Supreme Court decisions with other than nine voting justices dating back to the first Supreme Court. When thinking about the appropriate size of the Court, an issue of paramount importance is how effective Courts of varying sizes are at accomplishing the Court’s work – that is at deciding cases. The first figure below looks at the numbers of cases from each Court era where other than nine justices voted on the outcomes.

These 11,105 cases across time provide a surprisingly large set of cases. Focusing even more granularly we can look at the percentage of merits cases by Term that were decided by non-nine member Courts.

There are significant differences across time as well as is apparent in the figures. Supreme Court jurisdiction has also changed much through the Court’s history as its moved towards much more discretionary choices in cases (a larger proportion of cases now come on cert). The second figure breaks down the full set of cases with other than nine voting justices by the main types of jurisdiction (cert is the only discretionary form).

The Court has had voting compositions from ten to one justice(s), leaving several even numbered permutations. The Courts with an even number of justices had the greatest possibility for indecision through evenly divisions.

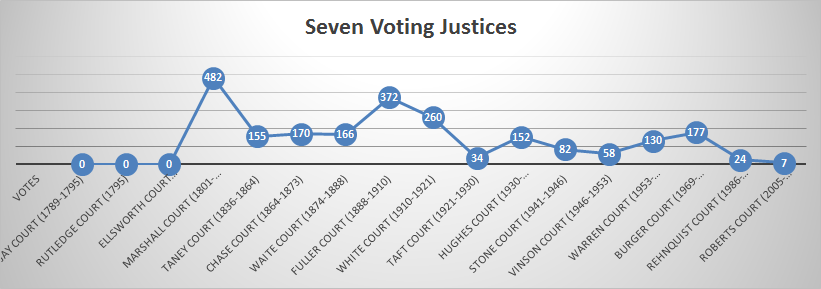

The next set of figures shows the number of cases per Court with varying Court sizes voting on the outcomes moving from ten justices to cases with four or fewer voting justices.

But what types of outcomes do these Court compositions lead to? Is there greater indecision with greater or fewer than nine voting justices? Equally divided Courts have never made up a majority of the Courts votes even in Courts with other than nine voting members. The figure below looks at the decision types with Courts composed of other than nine justices by Court era.

This presents a pretty benign picture of the role of equal divisions in the Supreme Court decision making even with Courts with other than nine members. The figure below presents absolute counts of the number of equally divided Courts by Court era

The number of these divisions is relatively low until the 20th century. The major increase occurred when the Court already was set with nine justices for many years – between the Stone and Burger Courts.

This can be compared with the number of cases where greater or fewer than nine justices voted that led to decisions that came down to a single justice’s vote.

There is a much more stable line of these one-vote majority decisions across time, than there is with equally divided Courts. The peak for these is also under the Burger Court.

The following figure with percentages equally divided Courts of total cases with other than nine voting justices looks somewhat different from the figure that focuses on the absolute case counts:

This figure shows a peak during the Vinson Court, although all Court eras with more than 1% of the total decisions from equally divided Courts were after the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1869.

There is a lot of data to digest from this post. What are the key takeaways?

- There have been thousands of cases where other than nine justices voted and the Court still was able to come to decisions on the merits.

- These cases were heard during years where the Court’s size was set to nine-members as well as when the Court was structured with other numbers of justices (these Courts have been composed of ten to one justice(s)).

- A relatively small portion of the cases with decisions from other than nine justices ended in equally divided Courts.

- The percentage of cases decided by equally divided Courts increased significantly in the 20th century although it has diminished in the last several Court eras.

Basically there appears to be nothing inherently wrong with the notion of a Court of a different size than nine. It should continue to function as Courts with an even number of members have historically come to decisions as well. Importantly though, when the number of justices on the Court has been set to any number other than nine, this decision was made by Congress through legislation. The hold out on hearings for the Supreme Court nominee, Merrick Garland, is unprecedented and there are political processes in place that could achieve the same outcome of an eight-member Court. Thus there are data to back up the proposition that the Court will not fail with other than nine-members. There are more politically credible ways to achieve alternative Courts sizes though than merely suppressing the Senate vote.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

Statistics compiled by: @SamuelPMorse

Raw data from The Supreme Court Database (Legacy Set)

Updated 10/30/16

8 Comments Add yours