Congress has historically low levels of public approval. Current Gallup Polls place Congress’ approval rating at around 18%. The Supreme Court’s approval rating tends to hover much higher – generally around the 50% level. One reason for this disparity is from sense that the Supreme Court does not engage in politics in the manner of other governmental institutions (a flimsy assumption at best). Another reason is that the Supreme Court gets its work done, while Congress often does not (hence the gridlock). The Supreme Court takes up a number of cases every year and even though this number is much lower than in the past, the Court tends to act decisively with almost every case it hears. This Term has been an exception to this norm where the Court has divided its vote on several cases so far leaving them undecided. The Court also still has yet to rule on over 20 cases it heard on oral argument, which is a disproportionately high number at this time of year compared to the Court’s typical annual decision calendar.

Much of the recent commentary on the Supreme Court focuses on how the current Court composition of eight Justices, with four tending towards the liberal end of the ideological spectrum and four tending towards the conservative end, is to blame. While there is no proscribed number of Justices that must sit on the Supreme Court and the number has fluctuated over time, a Court with an even number of Justices is prone not to reach consensuses, especially when there is built-in ideological polarization (an interesting counterargument examines why eight Justices might be a preferred number to nine). This situation sounds a lot like the one that Congress often faces leading to intense gridlock and exacerbating the public’s general lack of faith in that institution.

The Court has ruled in 41 cases with the eight Justice composition. Although this seems like a lot, it is not so great in the greater scheme of the Supreme Court. Moreover this Court composition is not likely to remain static there will be eventual turnover in Justices and eventually (termed loosely) the Senate will hold confirmation hearings for a new Justice.

The number of cases that the Court has yet to decide on this Term is not the only noteworthy aspect of the Court’s remaining business this Term. The Court has yet to rule on the more anticipated cases and the ones under greater public scrutiny. The fact that many of these cases remain undecided is logical based on the Justices’ own affirmations of the difficultly of coming to a consensus with eight Justices. As a factual matter, when the Court has ruled in salient cases it has, in several instances, failed to reach a firm decision. As examples, the Court divided evenly in Friedrichs, a highly anticipated case regarding teacher unions and remanded Zubik, which has far-reaching implications for the ability of businesses to disagree with aspects of current healthcare mandates based on their religious affiliations, to the lower courts.

The Court often saves many of its cases with more divisive issues until the end of the Term, but there is intense speculation that the Court’s composition and the Justices’ frustration with their inability to reach decisions in many of these cases has further complicated the process.

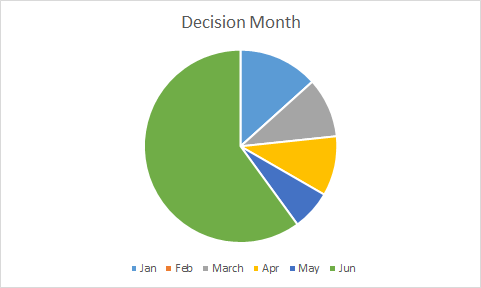

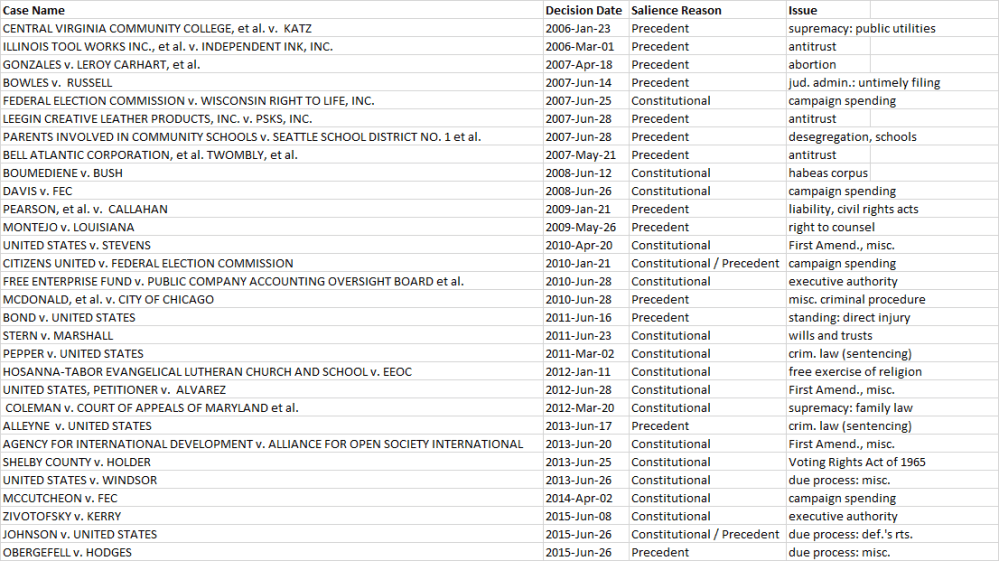

Each Term, the Court looks at important cases across many dimensions. One way to measure the importance of the Supreme Court’s cases that can be applied somewhat uniformly is looking at when the Court is asked to look at the constitutionality of a federal statute or the validity of one of its precedents (this is akin to a scholarly measure known as legal salience). Given the importance of decisions that fall into these two categories it will be interesting to see if these types of cases divide the Justices and ultimately lead to Supreme Court indecision. The cases that fall into these categories also often deal with issues that are in the public spotlight. Consequently, many of these decisions are made at the end of each Term. There were 30 decisions from the 2005-2015 Term where a federal statute was ruled unconstitutional or where Supreme Court precedent was overruled (based on coding in the United States Supreme Court Database). Of those 30 decisions, the Court decided 60% in June. The figure below shows the breakdown of when these decisions were released by month.

The following table shows the cases within these categories and main issue dealt with in each case since the 2005 Term.

There are multiple cases in several of these issue areas including antitrust (3), campaign spending (4), criminal law sentencing (2), due process (3), executive authority (2), and First Amendment (4).

Focusing on this Term, the first case that the Court decided with eight members where one of its precedents was called into question led to an equally divided Court. In Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, which examined whether or not to overrule the decision in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, the Court failed to reach a decision.

Although the Court ruled on question 2 in the second case, California Franchise Tax Board v. Hyatt, the Court did not rule on question 1 which had to do with the validity of its previous decision in Nevada v. Hall.

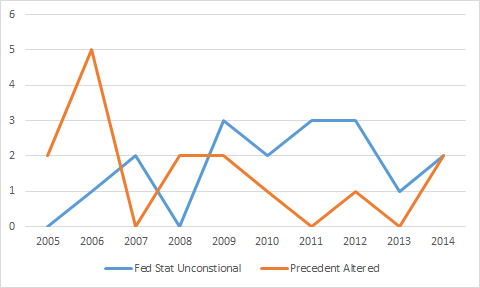

The Court occasionally brings up these issues sua-sponte or based on the case briefs even though these are not based on questions clearly before the Court. Based on the cert questions there are two other such cases still pending decisions this Term (examining constitutional challenges to federal statutes), Voisine v. United States and McDonnell v. United States. As the figure below shows, there has been fluctuation by Term in the number of cases where the Court engages in precedent alteration or rules federal statutes unconstitutional since Justice Roberts became Chief.

The fact that the Court chose to hear (at least) four such cases this Term should not be surprising, since the Court decided on the cases to hear this Term while it was still composed of nine Justices. What will be interesting, however, is how long the Court remains a Court of eight, and how quickly the public’s support and faith in the Supreme Court wanes as a consequence of this composition.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

3 Comments Add yours