Amicus briefs filed before the Supreme Court are most commonly used as a tool for interest groups use to convey their positions (for a look at interest groups’ use of amicus briefs see this article by Professor Paul Collins). This is not the sole use of such briefs though. Non-party individuals and groups that have an interest in cases also file these briefs – albeit less frequently.

Academics compose a coherent group of repeat amicus filers. The motivation behind these filings varies as sometimes these individuals are recruited by parties to present their viewpoints, while other times these academics have particularly noteworthy positions in cases that they wish to articulate. These expressed positions are quite different from the other main mechanism through which professors make their voices heard in the Supreme Court – through citations to their law review articles.

While law review articles are typically written by law professors, amicus briefs are submitted by a more diverse group of scholars, often including social scientists along with legal academics. Through filing amicus briefs, certain professors also bridge the often hard to overcome scholarly-professional legal divide.

When do these briefs make an impact on the Court? One way we know they made an impression on the Justices is when they are cited in the Court’s opinions. To be transparent, professors often are present on amicus briefs filed for interest groups and this post does not examine such briefs. Instead, this post focuses on those instances where the named group on the brief is either “professor(s)” or “scholar(s).”

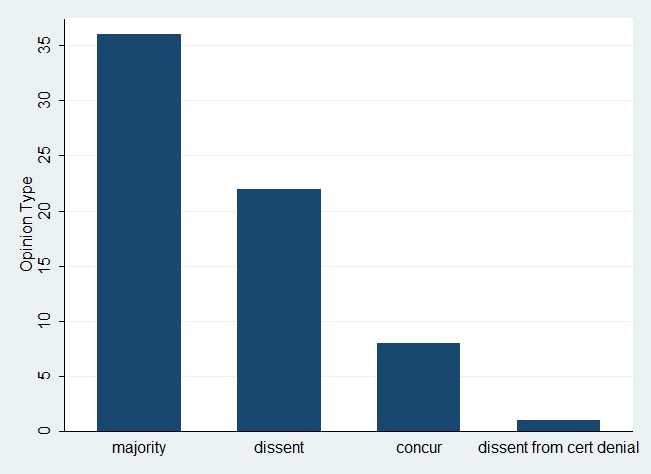

Amicus briefs filed on behalf of professors are not often cited in Supreme Court opinions. There are only 66 instances where briefs filed by “professor(s)” or “scholar(s)” are cited in the Court’s opinions. Below is the breakdown of opinion types in which these briefs were filed.

These briefs are primarily cited in majority opinions although they are cited in a fair amount of dissents as well. They are often mentioned in dissents in the same cases where they are cited in the majority opinions. The one instance where one of these briefs was cited in a dissent from denial of certiorari was by Justice Breyer in the case of Delling v. Idaho (the cited brief was filed on behalf of 52 Criminal Law and Mental Health Law Professors).

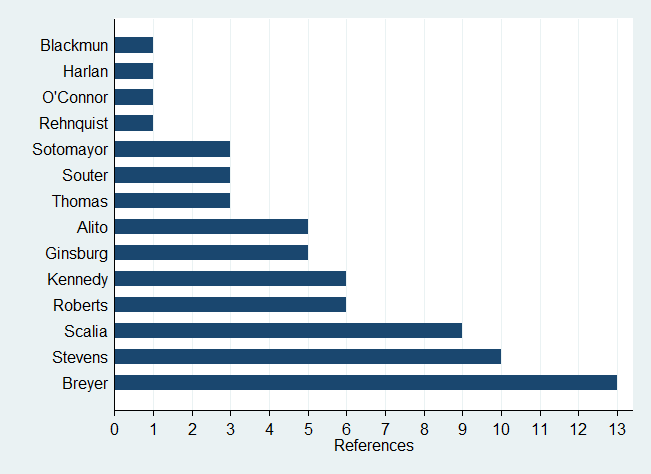

Justice Breyer is actually the Justice that has cited professors’ amicus briefs the most.

The modern nature of amicus briefs filed on the behalf of professors is notable in this figure. The only Justices who had significant histories on the Court prior to the Rehnquist years are two of the Justices with one such cite, Justices Blackmun and Harlan.

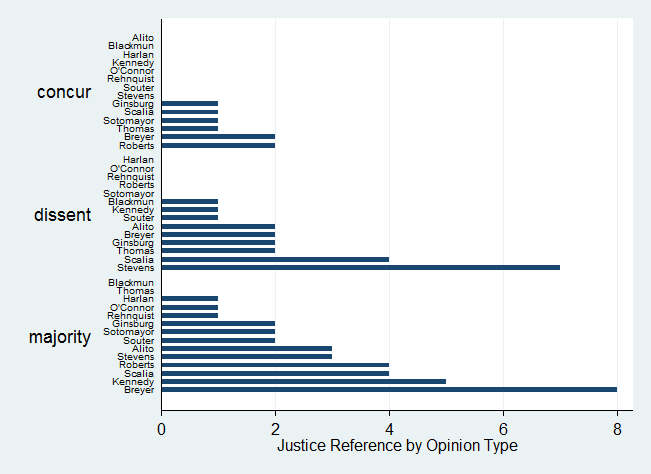

Breaking these briefs down by brief type and by Justice, we see where the Justices’ practices differ.

While Justice Breyer cited the most amicus briefs from professors in majority opinions, Justice Stevens cited the most in dissent. In majority opinions Justices Kennedy, Roberts, and Scalia cited these briefs more than Justice Stevens and in dissent Justice Scalia cited more of these than Justice Breyer who cited the same number as Justices Thomas, Ginsburg, and Alito. Justice Breyer and Justice Roberts both cited two such briefs in concurrences.

Amicus briefs on behalf of professors are predominately (although certainly not always) mentioned in highly politicized cases. The following figure tracks the cases where more than one such brief was cited.

Somewhat interestingly, two of the nine cases listed are the only two 2nd Amendment cases that the Court has heard in the last more than half-century, McDonald v. Chicago and District of Columbia v. Heller. Two such briefs were also cited in the marriage equality case Obergefell v. Hodges.

A question that the cases where these briefs are cited raises is whether briefs filed on the behalf of professors are seen as more neutral instruments than amicus briefs filed by interest groups. Are they methods of persuasion that are viewed by the Justices as less tied to moneyed interests and more objectively written than other amicus briefs? Possibly in some instances, some of the Justices view professors’ briefs in this light. The growth of both this type of amicus filing generally and the number of these briefs cited in the Court’s opinions over time at very least shows a strengthening of this type of advocacy before the Court.

One Comment Add yours