Several of the Justices were on speaking tours in recent weeks moving through academic venues and discussing the contours of the current Court in somewhat guarded tones (which is not surprising given the general tenor or Supreme Court Justices outside of the Court and based on the backlash against Justice Ginsburg’s incisive comments concerning Presidential candidate Donald Trump). In particular, Justices Sotomayor and Kagan discussed the lack of diversity on the Court. Justice Kagan referred to a “coastal perspective” while Justice Sotomayor in a more direct manner stated that “[t]he Supreme Court is never going to be a melting pot reflective of the country.”

In a separate speech at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, Justice Sotomayor described how her experiences as a Hispanic and a woman are only pieces that factor into her decision-making as a “human being.” The discussion of the relevance of diversity on Supreme Court decision-making are nothing new. Sidley Ulmer penned several studies that highlight this relationship in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Lately, however, this has become more of an object of discussion as a normative matter (see for instance this article by Vanderbilt Professor Tracey George).

The lack of diversity on the Court seeps its way down to the clerks as well, as they are generally culled from the top few law schools in the country thus creating a small pool of potential candidates. Breaking from these expectations, Justice Sotomayor made headlines earlier this year by hiring University of Hawaii Law School graduate Kamaile Turčan for an upcoming clerkship.

This introduction is the lead in to a discussion of the backgrounds of the Justices – not only those from the current Court but historically as well. When we think in historic terms of members of the federal government, there is a strong predisposition towards older white, Christian men. The Supreme Court is no different. This post uses data from the Supreme Court Justices Database (from Professors Lee Epstein et al.) which aggregates social characteristics of every nominee to the Supreme Court through Justice Kagan.

These distinct characteristics for Supreme Court nominees is quite apparent when looking at the breakdowns by gender and race. The figure below shows the percentage breakdowns of the races and genders of the 141 individuals nominated to the Supreme Court through Justice Kagan.

Although only a modest difference, the only push towards diversity in these factors has occurred since the second half of the 20th century.

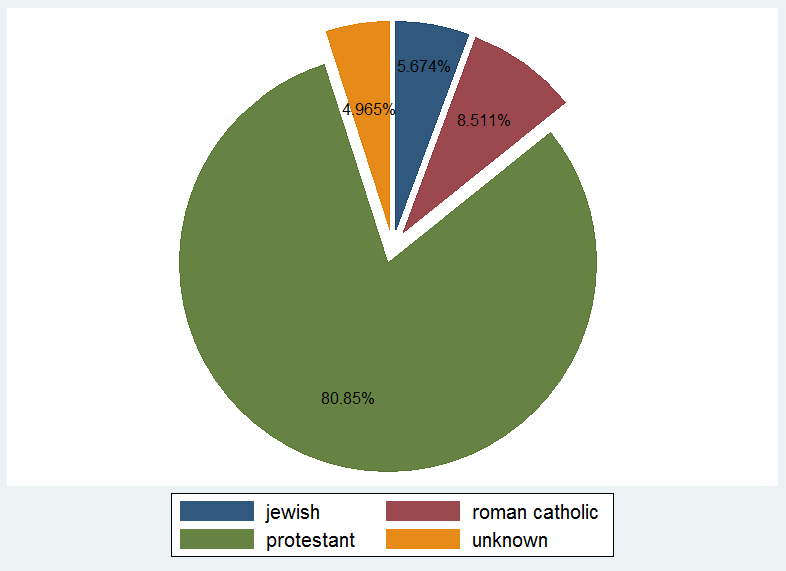

The nominees’ religions are moderately more diverse, although, at least historically, there is still a strong commonality.

Presidents have pushed back against this trend, however, particularly in the 20th century.

These subtle changes over time point to a lessening of the overwhelming homogeneity present in the nominees for Supreme Court Justices, although this is clearly nowhere in the realm of the diversity of the American population. There are several other characteristics captured in the data – some of which point to a modicum of diversity while others show a system that is quite resistant to change. In the area of some diversity, the following figure looks at nominees’ families’ social-economic statuses.

These subtle changes over time point to a lessening of the overwhelming homogeneity present in the nominees for Supreme Court Justices, although this is clearly nowhere in the realm of the diversity of the American population. There are several other characteristics captured in the data – some of which point to a modicum of diversity while others show a system that is quite resistant to change. In the area of some diversity, the following figure looks at nominees’ families’ social-economic statuses.

Here there is potentially less of an upper-class bias than one might expect, although there is a definite predisposition towards more wealth. This should not be surprising, however, given other commonalities between the nominees. When we look at the law schools of nominees focusing on the schools where more than two nominees attended we are left with a very short list.

When we look at nominees’ fathers’ occupations (those with more than two instances in the data) there is a strong trend towards lawyers although there were also several involved in farming and landowning (note the handful of plantation owners in this mix).

Finally, in response to the claim of coastal bias, the figure below breaks down the states where nominees were born if more there were more than two nominees born in that state.

Four of the top five states are, as expected, in the middle and northeast. There is also a clear bias towards the east coast across the board as California is the only western state where more than two nominees were born.

What can we take away from these data? First the Justices are correct that the Court is not a melting pot. There is a formula of attributes that is almost required of a Supreme Court nominee. “Almost” is key here, however, since some of these “requirements” seem to be softening. The cookie-cutter image of a SCOTUS nominee as a white, Christian, upper-class, male, from Harvard or Yale Law School, with a family steeped in legal tradition, and born in the northeast no longer holds in all instances. How does Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland mesh with these criteria? He is a white, Jewish, male, from a middle/middle-upper class background, he attended Harvard Law School, his father ran a small advertising business, and he was born in Chicago. Based on these factors he falls fairly close to the norm for Supreme Court nominees.

For those seeking greater diversity on the Court, the modest changes to Supreme Court nominees’ sociodemographics over time are obviously no cause for rejoice, only a suggestion of a loosening and of a potential for a further loosening of what used to be hard and fast constraints.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

Data compiled from the Supreme Court Justices Database

For another short post on Supreme Court nominees’ demographics see here.

9 Comments Add yours