Well before he is even ready to take control of the Oval Office, President-Elect Trump is engaging in unique Executive Branch politics. In terms of the Supreme Court vacancy, Trump, who has an acute awareness of how to use media and spin to his advantage, released two lists totaling twenty-one potential nominees for the seat on the Court. This is an unprecedented number of possibilities that was widely approved by conservative publications and scholars. Not only is the number of potential picks something novel from a president-elect, but also are the types of individuals on the list. The potential nominees include nine current federal court of appeals judges, nine state supreme court justices, a senator, and two federal district court judges. Although several of the leading candidates appear to be federal court of appeals judges (the typical prior role for a Supreme Court nominee) as a current poll hosted by Fantasy SCOTUS shows, people still believe there are other viable candidates.

History

Judges without federal court of appeals experience on the Supreme Court are far from the norm. In recent history the only prior judges on the Supreme Court with non-federal court of appeals experience have been Justices Souter (State of New Hampshire Supreme Court Justice from 1983-1990 before his appointment to the First Circuit Court of Appeals), Justice O’Connor (State of Arizona Court of Appeals, Div. 1 Judge from 1979-1981), and Justice Sotomayor (Federal District Court Judge for the Southern District of New York from 1992-1998 before her nomination to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals). Prior to that the last Justices with state supreme court experience were Justices Brennan and Cardozo. The only other Justice with state intermediate court experience was Justice Brennan. Before Justice Sotomayor there were two failed nominations of judges with prior federal district court experience – George Carswell, a Nixon nominee and William Thornberry, a Johnson nominee. The Supreme Court Justices with federal district court experience prior to Justice Sotomayor were Justices Whittaker and Justice Sanford (who took his seat on the Court in 1923).

This election has been a bit of an anomaly where both presidential candidates were quite particular about the policy positions they wanted in a Supreme Court nominee. In the past, Presidents have expressed what they looked for in nominees in more general terms:

Our agenda is quite simple—to appoint judges who don’t confuse the criminals with the victims and who believe the courts should interpret the law, not make it. That starts with the Supreme Court. It takes leadership from the Supreme Court to help shape the attitudes of the courts in our land and to make sure that principles of law are based on the Constitution. This is the standard to judge those who seek to serve on the courts—qualifications, not distortions; judicial temperament, not campaign disinformation. (Reagan 1986)

Let me give you a couple of examples, I guess, of the kind of person I wouldn’t pick. I wouldn’t pick a judge who said that the Pledge of Allegiance couldn’t be said in a school because it had the words “under God” in it. I think that’s an example of a judge allowing personal opinion to enter into the decisionmaking process, as opposed to strict interpretation of the Constitution. Another example would be the Dred Scott case, which is where judges years ago said that the Constitution allowed slavery because of personal property rights. That’s personal opinion. That’s not what the Constitution says. The Constitution of the United States says we’re all—it doesn’t say that. It doesn’t speak to the equality of America.And so I would pick people that would be strict constructionists. We’ve got plenty of lawmakers in Washington, DC. Legislators make law. Judges interpret the Constitution. (George W. Bush, 2004)

Compare these statements to President-Elect Trump’s response to a question about overturning Roe v. Wade during a recent presidential debate: “Well, if that would happen, because I am pro-life, and I will be appointing pro-life judges, I would think that that will go back to the individual states.”

This essentially implies that President-Elect Trump wants even stronger certainty that the individual he nominates will abide by his own policy agenda. With this in mind, Trump may well feel most secure with the appointment of a prior federal court of appeals judge.

Why?

Federal courts of appeals judges decide cases with similar issues to those the Supreme Court resolves. Although the Supreme Court hears a mix of cases from around the nation, both from federal and state courts, the bulk of these cases come from federal courts of appeals. In addition, federal courts of appeals judges are unelected unlike many state court judges and the only court more senior in the federal judicial hierarchy is the United States Supreme Court. This means the incentive structure for federal courts of appeals judges is similar to that of Supreme Court Justices and the only guiding principles of vertical stare decisis are the same as those for state supreme court justices – the decisions of the United States Supreme Court.

Without very much recent history of non-prior federal appeals court judges on the Supreme Court, judges with only other types of judicial experience may present themselves as less predictable candidates. First, there are few comparative counterparts to understand the similarities between judges on state courts or federal district courts and the United States Supreme Court. Second, the guiding principles on these other court types are different than those for federal courts of appeal and different in a manner that makes them less akin to the United States Supreme Court than federal courts of appeals.

History has also shown us the unpredictability of nominating judges with only prior state court experience. Although Justice Souter was nominated by President George H.W. Bush, he was a regular liberal votes on the Rehnquist Court. Justice O’Connor was often a swing Justice while on the Court and was not always a definite conservative vote in contentious cases. The last four Supreme Court nominees, all of whom were federal courts of appeals judges tend to vote as their appointing Presidents would have hoped – Justices Sotomayor and Kagan (Obama appointees) tend to vote on the liberal side of social issues, while Justices Alito and Roberts (George W. Bush appointees) tend to vote with the opposing, conservative bloc.

Cursory Comparisons (Supreme Court figures mainly based on data from the United States Supreme Court Database)

There is limited information that we can extract from the Justices O’Connor’s, Souter’s, and Sotomayor’s prior judicial experiences but these are the only sources of comparison with modern Justices (for comparisons I searched for all opinions from the justices on the lower courts. There are 86 opinions from Justice Souter and 40 from O’Connor. I sampled two hundred of Justice Sotomayor’s district court decisions and fifty of Justice Sotomayor’s federal appeals court decisions).

For starters, the proportions of case types the judges heard on the lower courts, aside from Sotomayor’s Second Circuit experience, were quite different than the proportion of case types they decided on the United States Supreme Court.

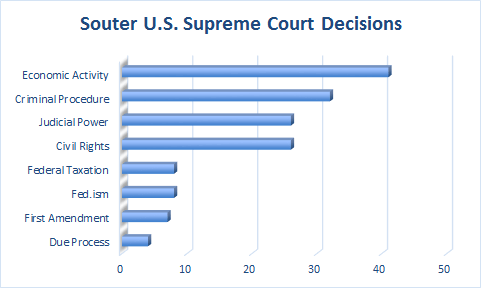

Justice Souter decided almost entirely criminal cases on the state supreme court (issues areas with few cases were removed from the charts).

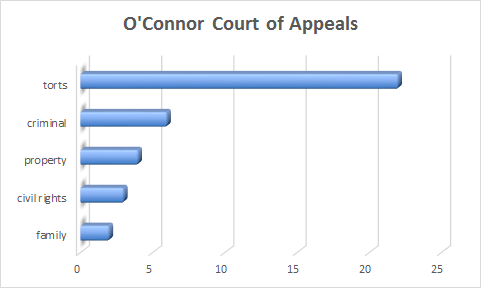

Justice O’Connor predominately decided tort cases on the Arizona appeals court.

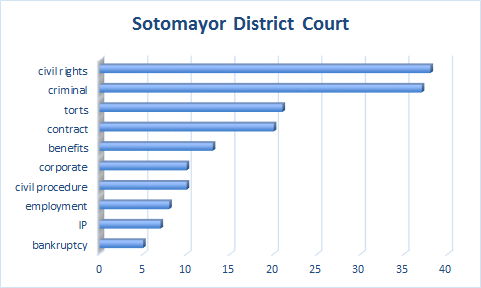

Justice Sotomayor mainly heard cases dealing with civil rights as a district court judge.

Comparatively, Justice Sotomayor decided mainly criminal issues in the sample of Second Circuit cases, but there is a much evener balance with other case types than we see with Justice Souter’s state supreme court decisions.

On the United States Supreme Court, both Justice O’Connor’s and Sotomayor’s decisions are/were predominately in area of criminal law with a good mix of other issues while Justice Souter decided mainly economic-related cases with a substantial number of criminal decisions as well.

Decisions

The ideological directions of the Justices decisions on the lower courts were also poor indicators of how they would vote on the Supreme Court. There are several institutional reasons for that. The constraints on lower court judges determine many case outcomes and leave little discretion to judges. This facet of judicial decision-making is combined with the fact that many lower court cases are fairly one-sided based on the facts, which also leaves little room for the Justices to decide based on their own preferences.

On the United States Supreme Court, Justice Sotomayor’s written decisions have been 41% conservative, 20% of her civil rights decisions have been conservative, while 59% of her criminal procedure decisions have been conservative. Justice O’Connor’s decisions were 59% conservative across the board with 55% of her civil rights decisions and 75% of her criminal procedure decisions conservative. Justice Souter’s decisions were 39% conservative with 31% conservative decisions in civil rights and 38% conservative decisions in criminal procedure. As a comparison, Justice Thomas’ criminal procedure decisions are 71% conservative and his civil rights decisions are 83% conservative.

On the New Hampshire Supreme Court, Justice Souter voted with the state (generally the conservative direction) in 87% of the cases he decided. In cases with clear outcomes for one side in the Arizona Court of Appeals, Justice O’Connor’s decided for the government’s position in four of five criminal decisions and for the government agency or business in twelve of twenty-one or 57% of her tort decisions (both typical indicators of conservative decisions). Justice Sotomayor’s district court decisions were 91% (31 of 34) in favor of the government’s position. Also 74% of her civil rights decisions on the federal district court were in favor of the defendant (the party opposing the accuser), which does not correspond strongly to her Supreme Court voting record.

By contrast, Justice Sotomayor supported the government’s position in 53% (9 of 17) of her Second Circuit decisions in the sample. In immigration cases she supported the initial plaintiff or voted against the government’s position in 72% (8 of 11) of the cases. These numbers much more strongly approximate her Supreme Court voting record than do any of the other three sets (Justice Sotomayor’s district court decisions, Justice O’Connor’s court of appeals decisions, and Justice Souter’s state supreme court decisions).

Based on this information, there appears little predictive capacity for how a judge will decide on the Supreme Court based on non-federal court of appeals lower court experience. This is not to say that federal court of appeals experience is a definitive indicator of how judges will vote on the Supreme Court. It isn’t. Justice Stevens served on the Seventh Circuit and was appointed to the Supreme Court by President Ford who had the intention of appointing a strong conservative vote for years to come. Unfortunately for President Ford, Justice Stevens became one of the staunchest and most predictable liberal votes on the Court for over three decades.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

With the assistance of: @SamuelPMorse

2 Comments Add yours