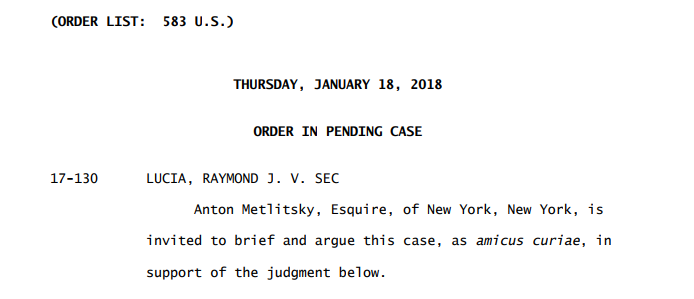

On January 18th, the Supreme Court released a short order requesting O’Melveny & Myers attorney Anton Metlitsky brief and argue the case of Lucia v. SEC supporting the decision below.

The case examines whether administrative law judges of the Securities and Exchange Commission are officers of the United States within the meaning of the appointments clause. In other words, since the administrative law judge was not appointed pursuant to the appointments clause, was the administrative law judge unconstitutionally appointed? The D.C. circuit’s opinion upheld the validity of the SEC’s administrative decision. This is the first case this in which an ordinary member of the bar was selected to brief and argue a case before the Supreme Court. It is an exceptional honor and an opportunity that can create many opportunities for the arguing attorney down the line. It is not a practice that has been largely empirically scrutinized. This practice also has its flaws. Like many Supreme Court practices, such invitations have been by and large male dominated. Only six of the 51 invitations or about 12% have gone out to female attorneys.

This post asks basic questions about this practice like who is given these invitations, when and in which cases do we see these types of invitations, and are the amici generally successful in these endeavors.

Where the Practice Started

The practice of inviting amici to brief and argue cases goes back at least to the late 1960’s (this can be differentiated from the practice of asking the Solicitor General’s Office to file amicus briefs at the cert stage examining whether or not the Court should entertain particular petitions). Under the modern practice, requests generally go out to former Supreme Court clerks. Anton Metlitsky, for instance, clerked for Chief Justice Roberts during the 2007 term. During that time the Chief Justice had the opportunity to get to know Metlitsky as well as Metlitsky’s strengths and weaknesses as a jurist. Based on this relationship, Metlitsky could be hand picked to brief and argue this specific case and possibly to fill in any information gap that the Court saw lacking from the lower court’s opinion or from the Respondent’s (SEC’s) merits briefs.

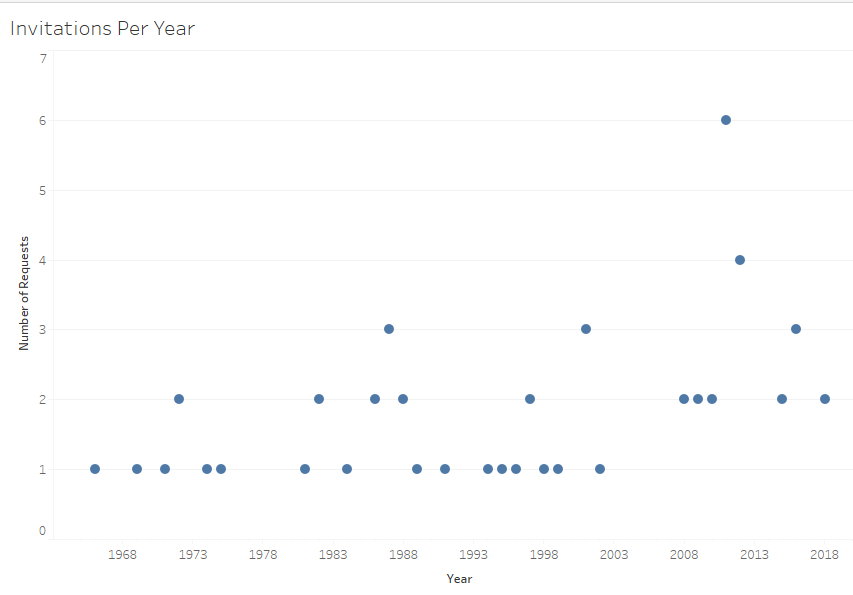

To locate these instances I looked through the Court’s orders for the language: “invited to brief and argue this case.” If the Court used substantially different language in a request, the request would not have made its way into my dataset. That said, the first such request went out to John Reed, who was not a former clerk, in the case of the Comissioner of Internal Revenue v. Stidger in 1966. At the time amici filings were much more infrequent and so there was a lot for the Court to gain from additional sources of information and analysis. Prior to this attorneys were invited to file amici briefs on the merits of cases like Kingsley Books v. Brown (the New York Attorney General was invited to file a brief in this case), but were not requested to participate in oral argument as well.

The practice of inviting amici to brief and argue cases started out slowly and has picked up the pace a bit since the earlier years. The following figure shows the frequency of such amicus invitations per year.

Amici Success

Many strong advocates had their first or one of their first Supreme Court oral arguments from such opportunities. While still a litigator, Chief Justice Roberts, a former Rehnquist clerk, had his second argument before the Supreme Court when he was invited to brief and argue the respondent’s position in U.S. v. Halper. This case was also Michael Dreeben’s (the modern Court’s most prolific advocate) first oral argument. Roberts’ side won the case by a unanimous vote.

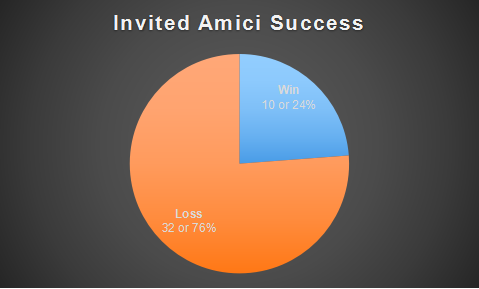

Invited amici are typically not as successful though. Looking across all cases with invited amici arguing to support the lower court’s decision, the loss rate far exceeds the win rate.

This suggests that these amici are asked to brief and argue difficult positions that the justices probably know from the early stages are not likely to succeed. Many of these cases also involve the federal government as the United States or one of its officers was a party in 30 of the 51 cases in which amici were requested to file a brief and argue. The average majority coalition in these cases was seven justices suggesting these were not particularly contentious decisions for the most part.

Most but not all requests for amici to participate in cases have been to support the lower court’s decision. In some instances though, the Court has asked amici to brief and argue other specific positions. In the cases surrounding the Affordable Care Act, for example, veteran advocate and former Rehnquist clerk H. Bartow Farr, III was asked to file a brief in the case and argue, “in support of the judgment of the Court of Appeals that the minimum coverage provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 26 U.S.C. § 5000A, is severable from the entirety of the remainder of the Act.” Meanwhile, Robert A. Long, a former Powell clerk, was asked to brief and argue, “in support of the position that the Anti–Injunction Act, 26 U.S.C. § 7421(a), bars the suit brought by respondents to challenge the minimum coverage provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 26 U.S.C. § 5000A.”

Links to the Justices

For the invited amici that were former clerks, the time elapsed between clerkship and when they were asked to brief and argue a Supreme Court case varied substantially. The least amount of time from clerk to argument was four years for former Alito clerk Adam Ciongoli. On the other hand 41 years elapsed between when former SG Charles Fried clerked for Justice Harlan II and when he was asked to brief and argue the position opposing the judgment below in Alabama v. Shelton. The average amount of time between clerkship and request to argue was almost 17.5 years across all former clerks.

The justices generally do not write the majority opinions when their former clerk was asked to brief and argue a case as the justice of the former clerk authored the opinion in only two of these cases. These justices were Justice Thomas in the recent case Beckles v. United States (former Thomas clerk Adam Mortara briefed and argued this case) and Justice Scalia in Setser v. United States (former Scalia clerk Evan Young briefed and argued this case). The justices also dismissed one such case, Ogbomon v. U.S., after the request was made but prior to oral argument.

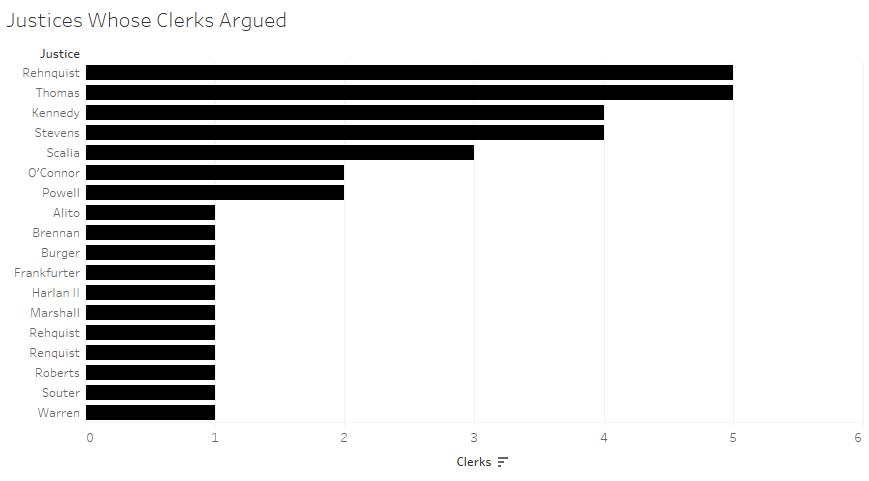

Some trends stick out when looking at these cases cumulatively. We can, for instance, split the justices based on which justice the former clerk who was invited to argue and brief the case worked for.

At the top of this list are Justices Rehnquist, Thomas, Stevens, Kennedy, and Scalia. The majority of justices had only one instance when a former clerk was an invited amicus although several justices, like Justices Ginsburg and Breyer, have yet to have one of their former clerks invited for this purpose.

The Decisions

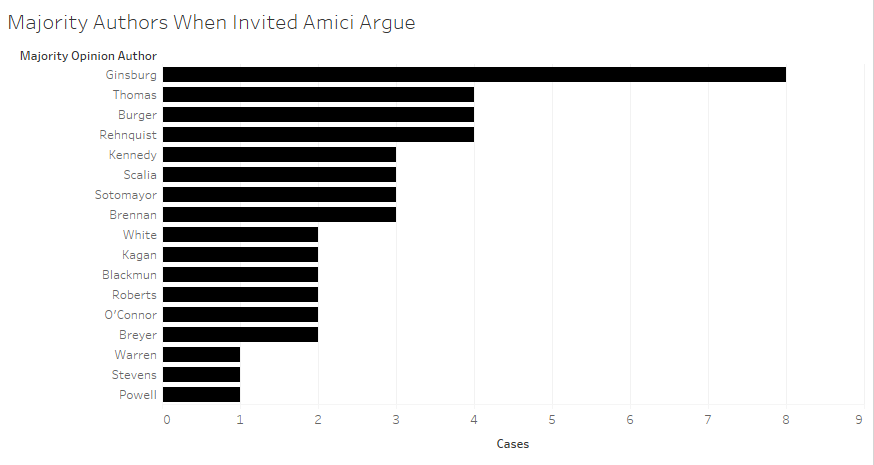

On the other hand, the order of justices shifts somewhat when we look at the majority opinion authors in these cases.

Justice Ginsburg has authored majority opinions in twice as many of these cases as the next most active justices. Justices Thomas and Rehnquist, however, are two of the three justices that authored the most such majority opinions after Justice Ginsburg.

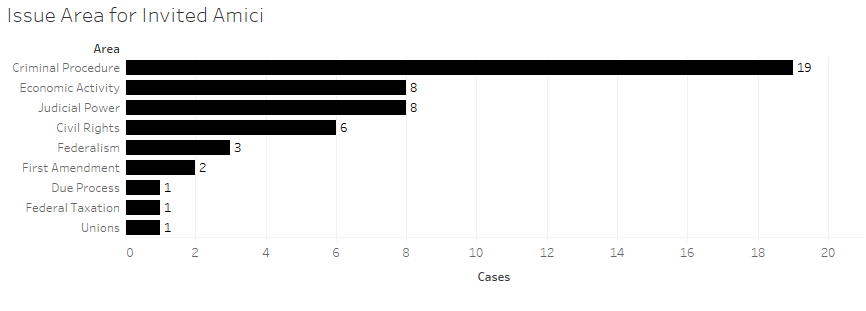

The cases which prompted the justices to invite arguing amici tended to cluster into several issue areas per coding from the Supreme Court Database. These clusters give us a sense of the types of cases where the justices were looking for informational support and legal analysis beyond their normal means.

The bulk of the cases had to do with criminal procedure. Several of Justice Thomas’ opinions fall into the realm of economic activity, an area in which he often authors opinions. Cases dealing with judicial power and civil rights are the other areas with a substantial number of cases with several cases dealing with federalism and First Amendment concerns as well.

Although these data only begin to explain which amici will be invited to argue before the Court and when such invitations will be made, they provide some perspective on the practice. Such opportunities helped promote several illustrious attorneys’ careers. Along with the already mentioned Chief Justice Roberts, Judge Sutton from the 6th Circuit was invited to argue (prior to his appointment as court of appeals judge) as were Miguel Estrada of Gibson Dunn, Michael Kellogg of Kellogg Hansen, 2nd Circuit Judge Barrington Parker, and 3rd Circuit Judge Stephanos Bibas. Suffice it to say, with a relatively small number of total invited arguing amici over the years, that such an invitation can be a fairly reliable indicator of a prodigious career to come.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

Those interested in the topic of amicus invitations should take a look at Prof. Kate Shaw’s much more extensive research on the subject.

17 Comments Add yours