An interesting debate was reignited by the Chief Justice’s majority opinion in Minnesota Voter’s Alliance v. Mansky. This debate surrounds the effect of oral arguments, if any, on the justices’ decisions. Here is one of the sections from Roberts’ majority opinion in that case that refers to oral arguments.

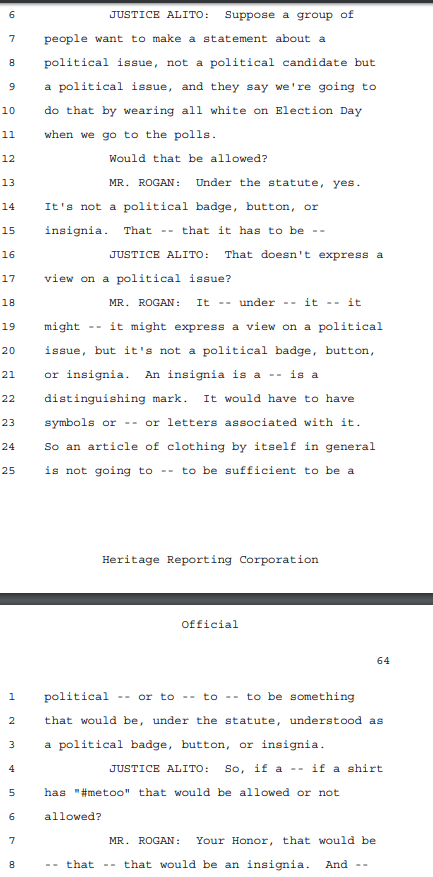

In this example, as is the case with many of the instances where justices cite oral argument transcripts, the authoring justice used the interaction to expose a weakness in a party’s argument. Roberts refers to the portion of the proceedings where several of the justices, including most notably Justice Alito, engaged respondent’s attorney Daniel Rogan about the extent of the apparel ban under the statute, in order to oppose that position.

Looking back at the oral argument transcripts, Alito seemingly caught the attorney in a trap where an affirmative response, while appropriate, could lead to a decision that the state statute was overly broad to pass constitutional muster. This raises the question about whether the oral arguments led to the outcome in the case in favor of the petitioners (I looked at a related question in separate post). Without information on the justices’ machinations, like the justices’ personal papers, it is nearly impossible to say this with any degree of certainty. Still, answers to this question both specific to this case and in Supreme Court cases generally say a lot about the importance of oral argument.

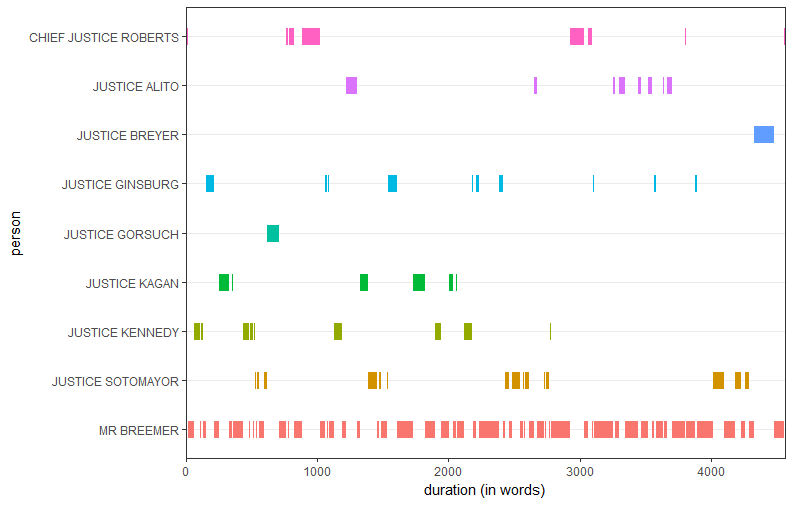

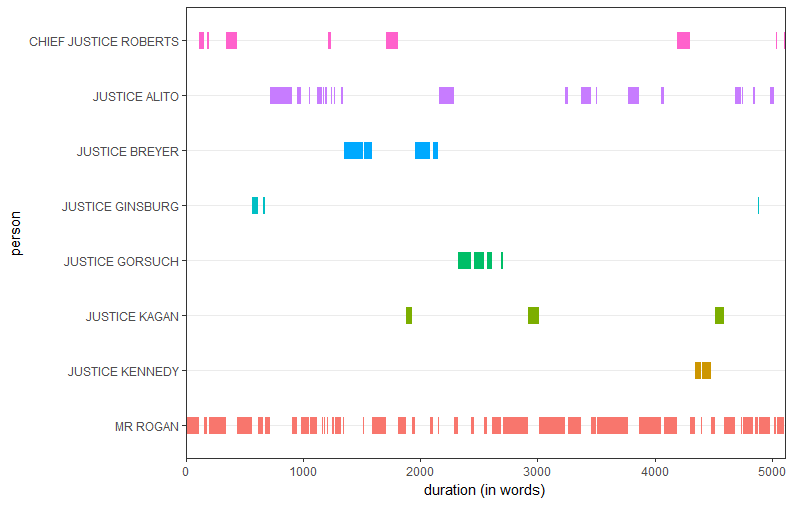

Although not conclusive, the justices’ decisions of when and how much to speak at oral argument is often telling of their voting positions. In Mansky the order and amount of speaking looked like the following during the petitioners’ turn:

And the following during respondents’ turn:

By breaking these figures down to their composite numbers, it becomes clear that Justices Alito, Roberts, Gorsuch, and Breyer spoke more during respondents’ turn. Speaking more to one side is often correlated with voting against that side, and although Thomas did not speak at oral argument, he generally agrees with coalitions that include Roberts, Alito, and Gorsuch. This leads to the question of whether oral arguments in Mansky helped move Ginsburg, Kennedy, and Kagan to the majority? I will return to this question towards the end of the post.

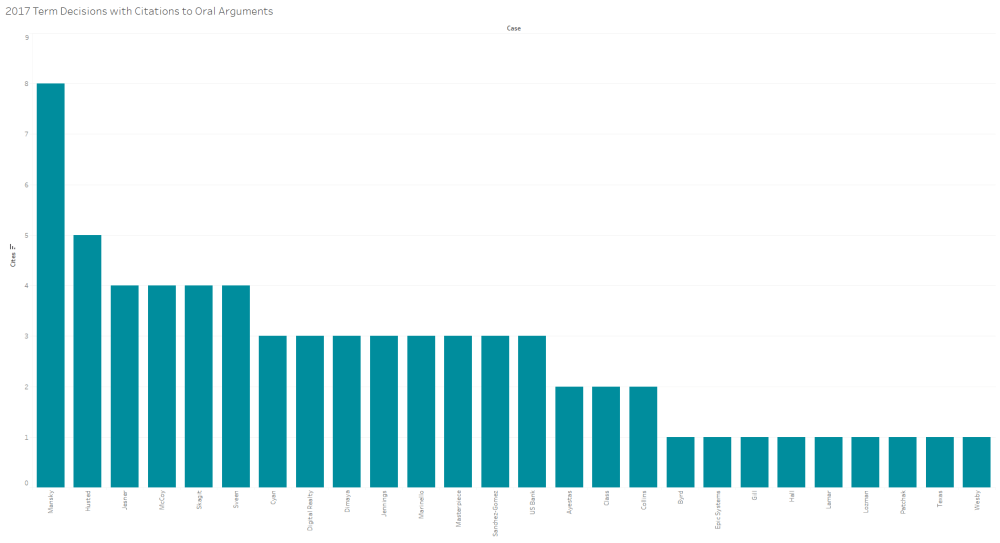

The justices cited oral argument transcripts in 69 distinct instances in opinions this term (multiple cites in one place were treated as one instance). The case breakdown of where these cites appeared is as follows.

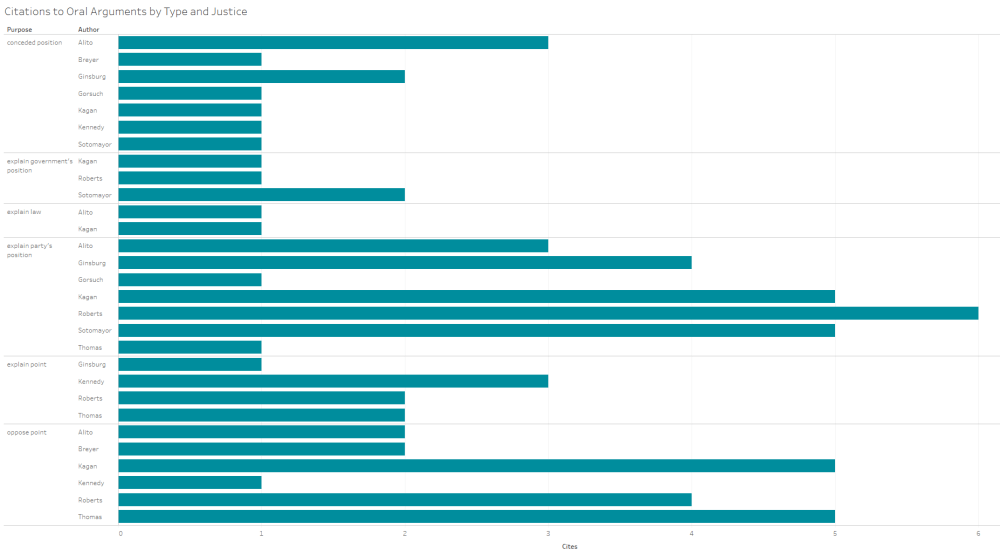

Roberts’ opinion in Mansky, the case with the most cites to oral arguments, mainly used the transcripts to oppose the position of the party/attorney involved in the cited segment of oral arguments. When grouped together into themes, other reasons for citations to oral argument transcripts this term aside from opposing a particular position include: describing when a party conceded a position, explaining the government’s stance on an issue, explaining the relevant law, detailing a party’s position, and explaining or illustrating the justice’s point.

Each of these types is easily identifiable. Here is an example of a concede position from Alito’s dissent in Collins:

In this instance, Alito merely cites oral argument transcripts to show that neither party disputed the cited point. While the justices may use these points to support their views in the case, these facts have the initial appearance of neutrality.

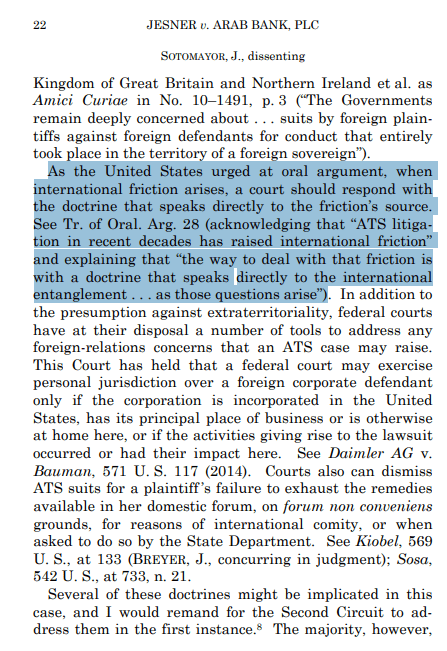

Arguments were also cited to explain the government’s positions in cases as Justice Sotomayor does in the following instance in her opinion from Jesner:

The United States’ position on issues is generally shown deference even if is not adopted by the Court. The regard the justices tend to pay to statements from the U.S.’ attorneys though shows that their arguments are at least cursorily examined as they are here.

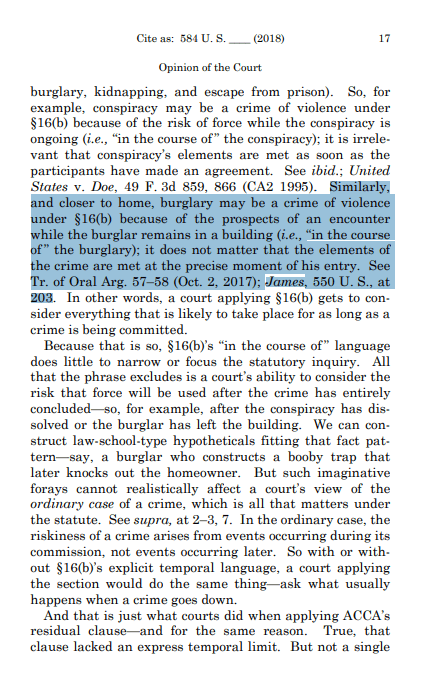

Oral arguments may also be used as a tool to explain the law. The following is an example from Justice Kagan’s majority opinion in Dimaya:

The oral argument transcripts in this instance are used as a tool of statutory interpretation. In such a situation oral arguments may have a neutral application or they may be used to show why a particular view of a law’s meaning is superior to another.

Outside of the law, oral arguments may also be used to lay out specific facts. When this is the purpose of the citation the justices may look for particularly favorable facts to their positions. Below is an example from Kennedy’s majority opinion in Lozman.

The scenario as Kennedy set forth provided specific details like the number of times Lozman attended these sessions. In doing so, Kennedy set the stage for various interpretations of what this regular attendance implies or conversely of the importance of the arrest on that particular occasion.

One final way that the justices cited oral arguments in opinions this term was to highlight a party’s positions that may or may not be adopted by the Court. The following example is from Justice Kagan’s majority opinion in Sveen.

The party’s position may be articulated to create a straw man argument that the authoring justice later deconstructs. This is the trajectory followed by Justice Kagan in the above instance. By citing the party’s own views on an issue, justices have the opportunity to engage in a secondary dialogue, not directly with the party’s attorney, but rather with the transcripts that expose the attorney’s positions.

These six types of oral argument citations are employed purposefully. With the benefit of party’s assessments, the justices often interpret particular arguments, often in order to explain why they are invalid or incorrect.

The justices’ individual uses of the types of citations so far this term is shown next.

The most frequent purpose of oral argument citations so far this term has been to convey party’s positions. Within this area Roberts is the most frequent citing justice followed by Kagan and Sotomayor. The rationale for this type of citation is often to develop an argument against the party’s position.

Justices may more directly oppose a party’s position as Justice Roberts does in Mansky by citing examples from oral arguments of miscalculated or erroneous answers. Rather than merely restating a party’s position, these often come up in hypothetical applications that the justices use to test the soundness of a particular argument. Kagan and Thomas are the two justices that followed this approach the most in their opinions. Thomas, while present, did not participate in oral arguments this term

Oral arguments most likely impact the justices on the margins. We may never know all instances where justices’ votes were swayed by the proceedings but we can make educated guesses as I did with the justices in Mansky by comparing the justices’ likely and actual votes (the likely votes may be at different points in time such as before and after oral arguments). Comparisons like these over time may shed additional light on both the justices’ uses for oral arguments as well as the impact these arguments make on case outcomes.

On an unrelated note: The justices have punted multiple high-profile cases that were argued this term. These include Benisek and Gill but also much of Masterpiece Cakeshop. The Court has not been shy about remanding gerrymandering cases in the past without much substantive guidance. It even did so last term with North Carolina v. Covington. What if Chief Justice Roberts, the master tactician on the Court, has learned the importance cooperation on the Court from the 8-justice Scalia-less Court of 2015 and 2016. For all of the Court’s political decisions under Roberts, Roberts now seems to shy away from 5-4 ideologically divided decisions in politicized cases. Without a ninth justice the Court managed to avoid big decisions in highly charged political cases such as Friedrichs, Zubik, and United States v. Texas. If Roberts prefers this outcome to ideological polarization maybe he and to a lesser extent the other justices are seeking such compromises over highly fractured decisions. In any case, just a thought.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

8 Comments Add yours