Oral arguments for the 2018 term are now complete. In a term where we have the potential to see heightened polarization on the Court like never before, oral arguments are impacted as well. One indicator of this harkens back to the previous term where all 5-4 decisions made across ideological lines ended in conservative victories. So far this term Alito, Thomas, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh have all been in the majority in all but one of the Court’s 5-4 decisions.

Oral arguments shed light on the interaction between justices in a unique way. They also are the only time that parties’ attorneys directly interact with the justices. Within this ephemeral frame, one of the only places where we can see and hear the justices work through case materials and seek answers to a variety of questions, multiple layers of interaction yield novel insights into the Court’s current dynamics.

Taking Control

Since oral arguments are limited in duration, time that is focused on any particular individual’s interests is always at a premium. Justices have the opportunity for counsel to answer their specific questions and to illuminate particular areas of inquiry that may not have been sufficiently resolved through the case’s briefs. Since the Court’s liberal minority is obviously at a voting disadvantage in ideologically polarizing cases, one way they still might attempt to gain some leverage in cases is through oral arguments. The first justice that speaks in an oral argument gets to set the initial tone for the argument and to specify the Court’s initial line of questioning. Since justices tend to follow up on their own questions, this sometimes manifests into prolonged dialogues between the first speaking justice and the arguing attorney.

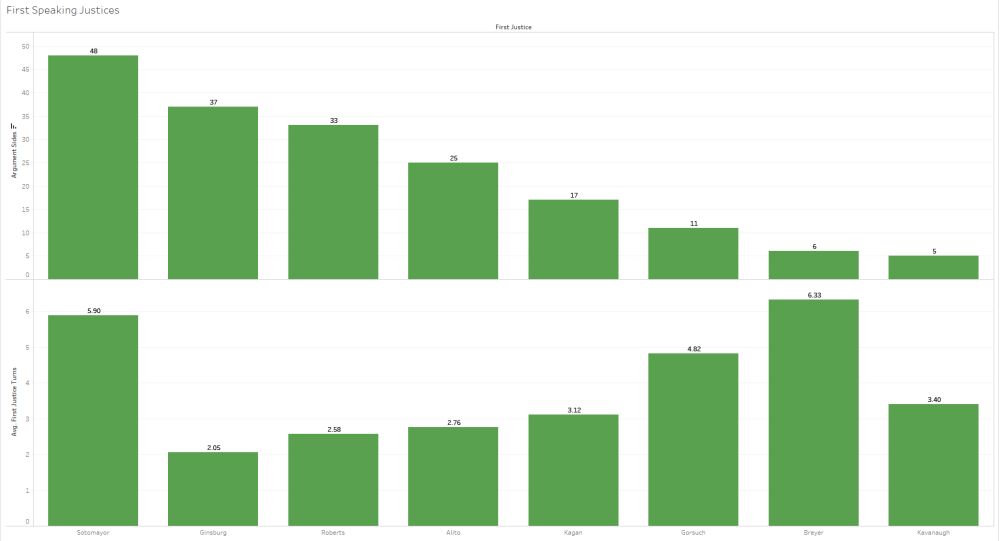

This term, the Court’s liberal justices often spoke first and held the floor after attorneys began an argument. The first figure shows the number of times a justice spoke first after an attorney’s opening statement in an argument as well as how many talking turns the justice took on average before another justice interjected. This looks separately at each attorney — petitioner, respondent, and amici – in an argument, but excludes petitioners’ rebuttals.

Sotomayor was the first speaking justice in more arguments than any of the other justices. She also engaged these attorneys to quite a degree by averaging 5.9 talking turns before a second justice jumped into an argument. Ginsburg, who is often one of the more reticent justices at oral argument in terms of total words spoken (she only said about 8% of the total words from all justices last term) began the second most arguments after Sotomayor with 37.

The liberal justices that were less frequently the first speaking justice might have made up for this by actively engaging the attorneys for prolonged periods when they did begin an argument. Although Breyer was the first speaking justice in only six arguments, he averaged 6.33 speaking turns before another justice jumped into the fray. While Roberts and Alito were the first speaking justices in more arguments than Kagan (and Breyer), Kagan surpassed both in her average turns before another justice began speaking with 3.12 compared to Alito’s 2.76 and Roberts’ 2.58 turns.

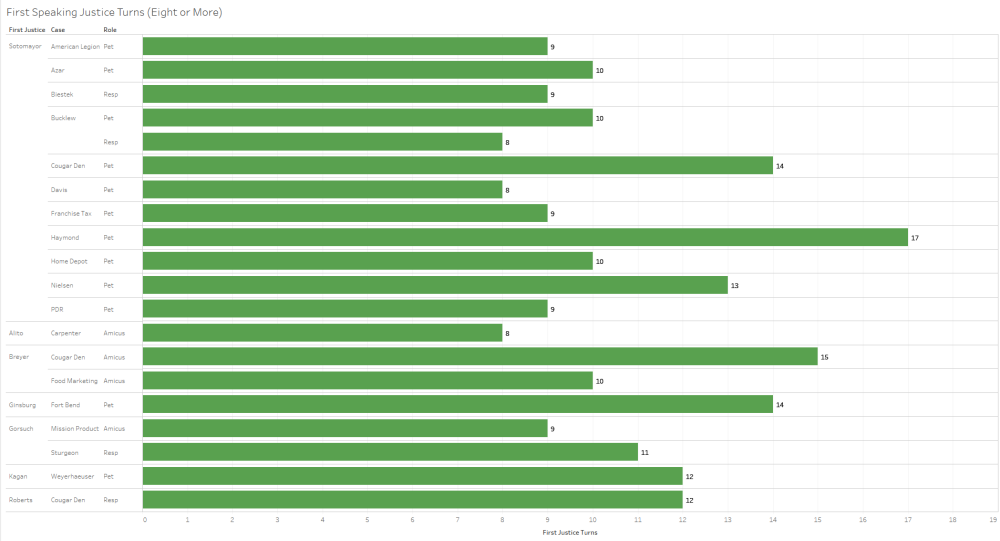

Sotomayor was not only the most frequent justice to begin speaking in arguments, but she had the most arguments where she took at least eight talking turns before another justice began speaking.

These instances, which show the most consecutive talking turns a justice took in an argument before another justice began speaking shows that Sotomayor had the most overall repeat turns in U.S. v. Haymond during Eric Feigin’s argument with 17, and also took the most opportunities of eight turns in a row or more in the aggregate with 12. All other justices had two instances at most of eight or more talking turns to begin an argument.

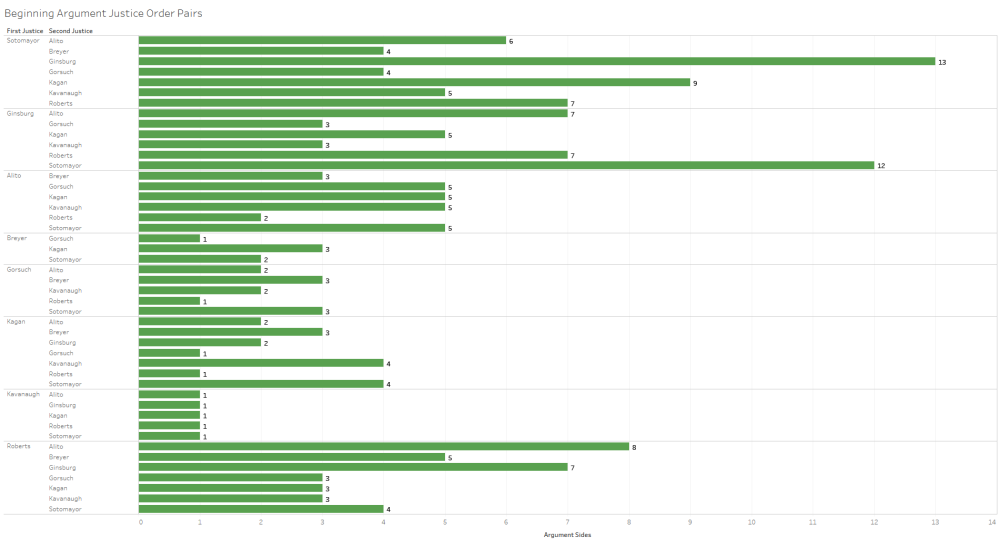

A related way that the justices can attempt to guide oral arguments is by picking up the questioning after the first speaking justice. Depending on their intention, second speaking justices can augment points the first speaking justice makes, or transition the attorney onto a different issue entirely. The next figure shows the number of times a given justice followed a first speaking justice in an attorney’s argument this term.

Sotomayor took the most turns as second speaking justice as well with 31. Alito and Kagan tied for second with 26 each. Sotomayor followed Ginsburg, her closest voting ally on the Court, in the most arguments (both for her and for any justice pair) with 13. Ginsburg reciprocated in this respect as she followed Sotomayor in the second most arguments with 12. Sotomayor followed Kagan next most at nine times. Sotomayor wasn’t hesitant to speak after her more conservative colleagues either as she was the second speaking justice after Roberts eight times and after Alito six times. Similarly, Ginsburg was the second speaking justice after Roberts and Alito seven times apiece (this was second most for her after her 12 instances following Sotomayor).

The other justices tended to have less variation in amount of times following particular justices. Roberts, for instance followed Alito most at eight times and Ginsburg second most at seven times. Alito followed Gorsuch, Kagan, Kavanaugh, and Sotomayor equally at five times each. These trends regarding the justices’ ordering of speaking gives a sense of the justices’ oral argument techniques and how certain justices manage to maintain their lines of inquiry for prolonged portions of arguments.

Advocate Opportunities

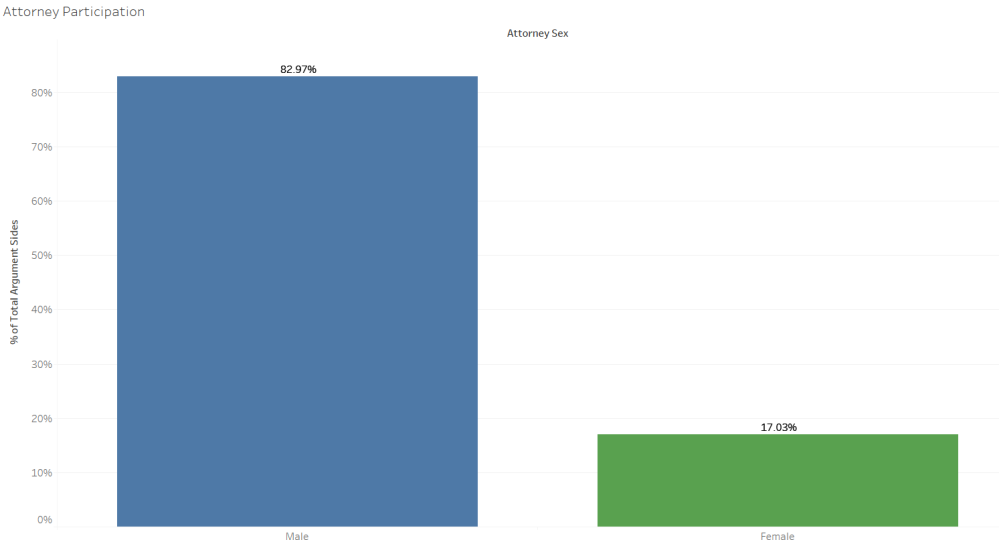

Supreme Court oral arguments are and historically have been a male dominated enterprise; especially with regards to the arguing attorneys. Women, for example, only made up about 18% of total attorney composition in arguments between the 2012 and 2016 Supreme Court terms. The 2018 term was much the same as the figure based on relative attorney participation below shows.

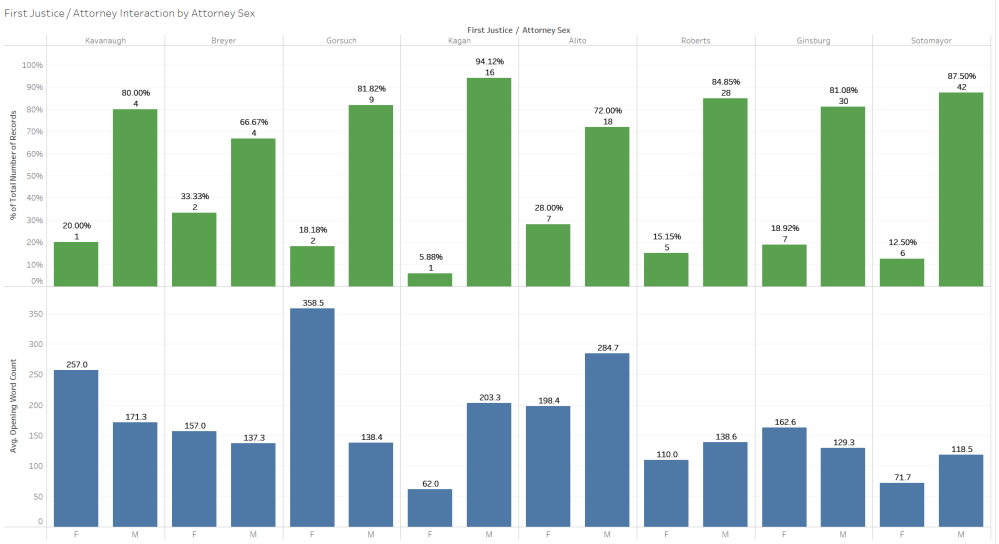

Since the attorney composition is so heavily weighted towards men, we might expect a similar distribution by justice for jumping first into oral argument depending on whether the arguing attorney is male or female. While this is generally the case there is some noticeable variation between justices. Another point encompassed in the next figure is how many words the justices let attorneys speak in their introductory remarks before they were the first to proceed with questions. The top part of the of the following graph shows the number and percentage of times a justice was the first justice to speak after male or female attorneys, and the bottom part shows how many words each justice let attorneys speak when the justice was first to interject depending on whether the attorney was male or female.

Justices Breyer, Kavanaugh, and Gorsuch each had limited opportunities as the first speaking justice and so their statistics are not very informative although Kavanaugh and Gorsuch maintained close male/female divisions to the overall 83%/17% baseline for interjecting after male or female attorneys. All three justices let female attorneys speak more words on average than men before jumping into the arguments.

Justice Kagan was much more likely to jump in first after a male attorney than a female attorney with 16 instances compared to one. Of the justices that frequently were the first justice speaking, Alito had the highest percentage of speaking first during a female attorney’s argument at 28% of the total opportunities he took. The other justices’ frequencies of interjecting depending on whether the attorney was male or female tended to be much closer to the actual difference in male and female attorney speakers for the term.

Of the five justices that were most likely to speak first after an attorney, Kagan only jumped in first once after a female attorney which discounts the statistical importance of her word count differential there. Alito, Roberts, and Sotomayor all jumped in sooner when female attorneys were at the podium while Ginsburg jumped in sooner with male attorneys than she did with female attorneys. Of these four justices, Alito let male and female attorneys speak more before jumping in than the other justices, but he also had the biggest difference in male to female attorney words allowed at just over 86 more words for men. This suggests Alito was tentative about when to jump in first generally, but was less hesitant during female attorneys’ arguments than he was with male attorneys.

Some of Sotomayor’s overall likelihood of speaking first among the justices may be related to the low initial word counts for both male and female attorneys when she was first to interject. The only justice that allowed fewer words on average for male or female attorneys was Kagan and that was with a single female attorney. Sotomayor allowed female attorneys an average of 71.7 words spoken before jumping into questioning. She was also the quickest justice on average to ask the first question when a male attorney was arguing, allowing male attorneys 118.5 words on average before jumping in.

Significance

During the 2018 term, the liberal justices were trying to define their roles on this majority conservative Court and to maintain some leverage over decision making even though they constitute a minority. Strategies at oral argument are one way this could be achieved; especially by setting the initial tone for the discussions during oral arguments.

We see the gender disparity for attorneys at oral argument remains as much of an issue as ever. The justices had differential involvement early in oral arguments depending on whether the arguing attorney was male or female. Kagan and Sotomayor were much more likely to jump first into arguments with a male attorney while Alito was the most likely on the balance to jump first during a female attorney’s argument. While not all of these behavioral choices are conscious decisions the justices make, they show some of the important differences that both ideology and sex played in the justices’ and attorneys’ involvements in 2018 oral arguments.

8 Comments Add yours