Supreme Court review is often thought of as mainly monitoring the federal courts and circuit splits. The reasons for this are obvious. Rule 10 of the Supreme Court Rules, the only (albeit non-compulsory) rule about what types of cases the Court should hear on cert, speaks about circuit splits before other types of cases.

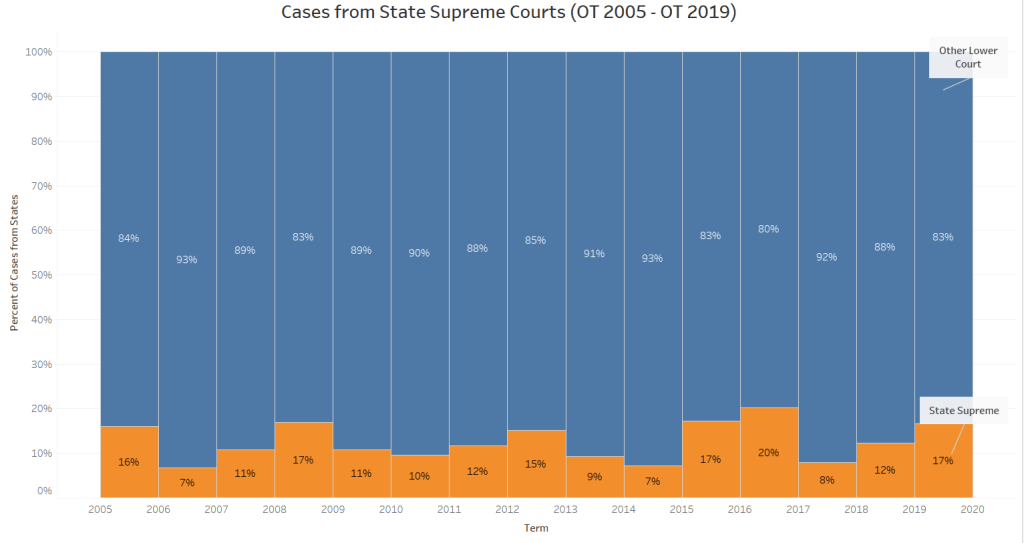

Surprising to some, the bulk of the cases the Court heard during OT 2019 was not from any federal circuit. More cases came to the Supreme Court cumulatively from state supreme courts, 11 or around 17% of the Court’s docket, than from any federal court. The Ninth Circuit had the most cases that led to Supreme Court review of the courts of appeals with 10 which equated to 14% of the Court’s merits docket.

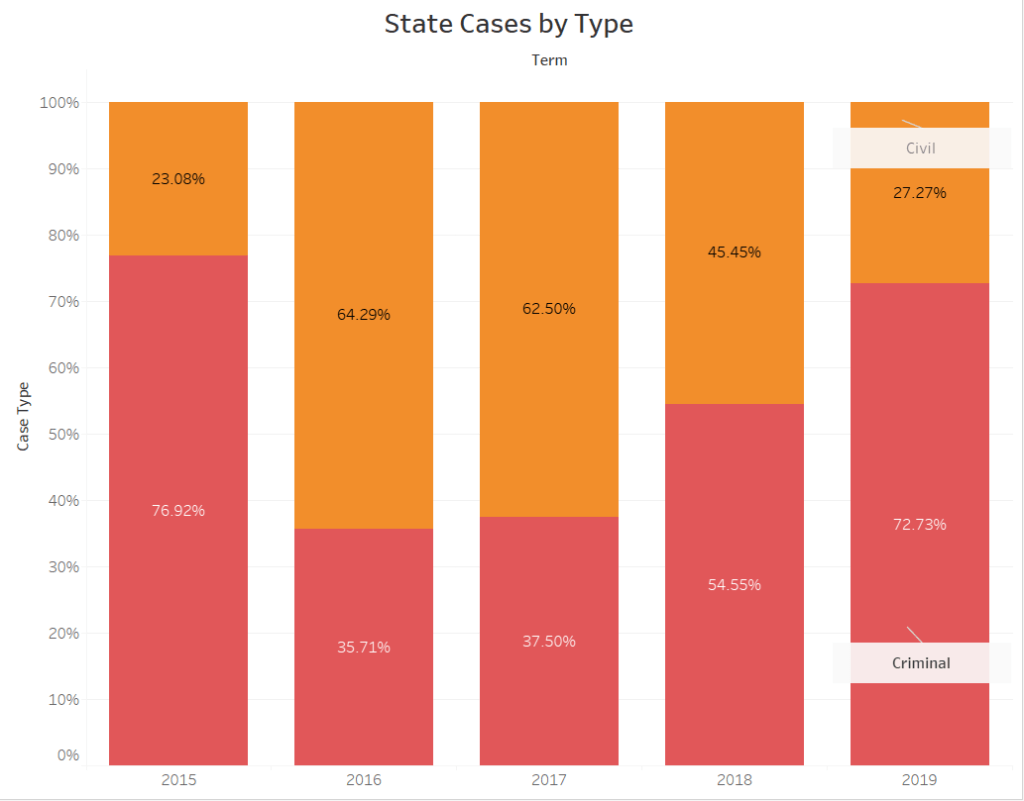

The cases from lower state courts were primarily criminal in nature with seven but included four civil cases as well. While this post focuses on the last few terms of Supreme Court review of state court decisions, Empirical SCOTUS took a longitudinal look at the Supreme Court’s review of state court decisions in a previous post.

So far, the Court has granted two arguments reviewing state court decisions for OT 2020 based around three cases. The first argument in Jones v. Mississippi looks at Eighth Amendment limits on life sentences for juveniles. The second argument, in Ford Motor Company v. Montana Eighth Judicial District Court, will focus on issues of civil procedure relating to necessary forum contacts for defendants.

Since the beginning of the Roberts Court, the split of cases from lower state and federal courts has, for the most part, hovered around this 10-20% state court case margin.

In OT 2019 almost 73% of the Court’s cases reviewing state court decisions were criminal rather than civil. Over the last five terms though, there has been considerable fluctuation in this balance between criminal and civil cases coming from lower state courts.

Oftentimes criminal cases coming from states are readily identifiable. First off, the state is listed as the petitioner or respondent in each of these cases. Second, by tackling high profile criminal issues like cruel and unusual punishment and various court protocols in criminal cases, these are often the cases that are the most closely tracked coming from state lower courts.

Amici play a large role in cases coming from state courts. Amici in these cases, while sometimes parallel to those who file in cases coming from lower federal court, also include state based organizations that handle more localized policy matters. These amici assert different interests than groups with nationwide coverage and offer the Court a glimpse of policy forecasts based on different sectors of the population. The specific state and local level amici were coded for this post in each case from a lower state court over the past five terms.

Focusing on this period from OT 2015 through OT 2019, the next graph presents three data points: it shows the number of state cases the Supreme Court reviewed each term, the number of state or local groups that filed amicus briefs each term, and the total number of amicus briefs filed in these cases in each of these terms.

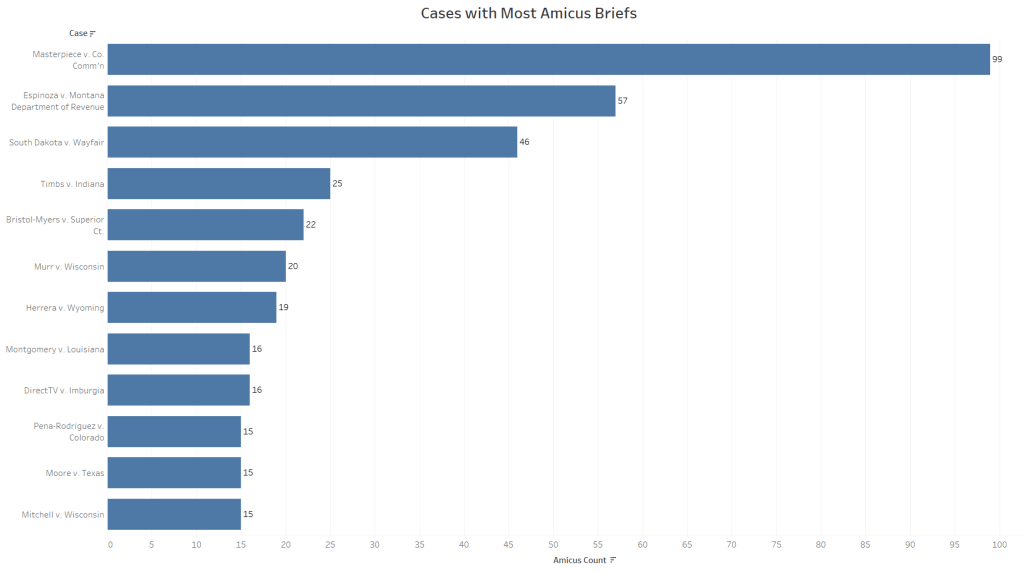

This past term included the most filings from state based amicus groups. The 2017 term saw the most total amicus filings in these cases and more than twice as many as in OT 2015. The bulk of these filings were in two civil cases arising in state courts: South Dakota v. Wayfair Inc. with 46 amicus briefs and Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission with 99 amicus briefs.

The cases for these five terms with the most amicus filings including the two cases mentioned above are covered in the following graph.

The only case that made the list for most amicus filings from OT 2019 was the religious liberty case, Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue.

To focus on the most active amici of this pack, the following graph uses information from the Supreme Court dockets to break down these filings into groups that filed in three or more cases.

The prominence of amici focusing on criminal law is evident from the NACDL (National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers) filing amicus briefs in more cases than any group other than the United States. National groups that file amicus briefs in a whole host of Supreme Court cases also led the filings in this group of cases coming from state courts. The Cato Institute, the ACLU, and the ABA are regular filers in cases from both federal and state courts. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce participates in many business-related cases before the Court. The Criminal Justice Legal Foundation is another example of a largescale criminal law focused group that participates in a many of these cases.

Certain clusters were removed from this graph but are relevant amici in this set of cases. These include academics who filed 63 amicus briefs in this case set, states which filed 43 amicus briefs, individuals who filed 32 briefs, politicians/judges/lawyers who filed 25 such briefs, and cities and local entities that filed six briefs in this set.

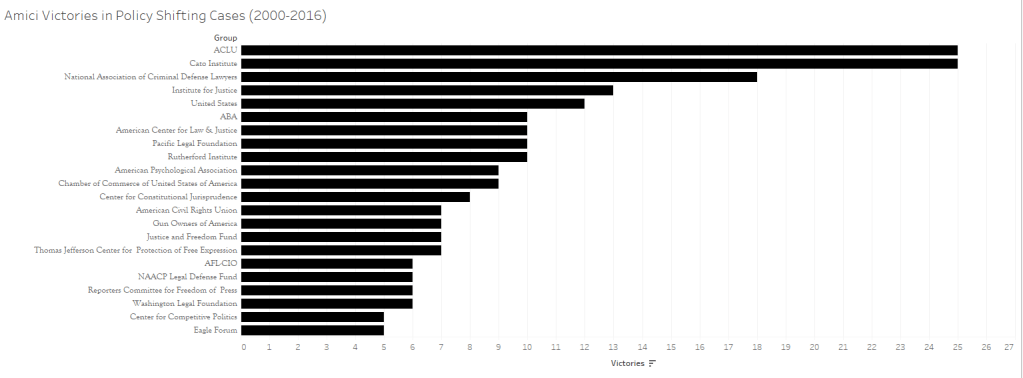

When viewing the following graph from a previous post looking at the most successful amici for OT 2000 through OT 2016, many similar groups are evident:

The overlap between groups in the two graphs highlights the importance of these state court cases to the most prominent amici before the Court. Groups that are in the state court list but not in this list of amici victories, however, pinpoint groups like the National Congress of American Indians, Multistate Tax Commission, and Reason Foundation, which might have distinct interests in the state subset of cases.

Since this post looks to nuances in state court cases that might be different from other litigation before the Supreme Court, a final measure of interest is attorneys with the most oral arguments in this set of cases from OT 2015 through OT 2019. These attorneys were divided into private attorneys from firms or groups, attorneys for state governments, and attorneys from the federal government who argued as amici.

With five oral arguments in these cases, Jenner & Block’s Adam Unikowsky argued in more of these cases than any other attorney. Hogan and Lovell’s Neal Katyal argued the second most of these cases with four along with federal government attorney Ann O’Connell. Other law firm attorneys on this list include some of the most highly touted members of the Supreme Court bar including Seth Waxman, Jeff Fisher, Tom Goldstein, and current Ninth Circuit judge Eric Miller. State government attorneys on this list include former Colorado Solicitor General Frederick Yarger, former Kansas Solicitor General Toby Crouse, current Washington Solicitor General Noah Purcell, and current Louisiana Solicitor General Elizabeth Murill.

While the world of Supreme Court litigation coming from state lower courts holds clear differences from Supreme Court cases coming from lower federal courts, the similarities are often more prominent. The types of cases and amicus filers subtly differ between the two group but many of the amicus filers are the same big-name interest groups. The prominence of state court based criminal litigation compared to the civil suits coming from federal courts might be noteworthy as well. At the end of the day, the law firm litigators that argue many of these cases are the same familiar faces that argue the bulk of other cases before the Court. That all said, a point that clearly jumps out of this analysis is that cases going to the Supreme Court from lower state courts are just as important as those from federal courts and that more focus should be placed on comparing and contrasting these cases with those from lower federal courts.