Judge Amy Coney Barrett, now Supreme Court nominee, has followed a well-worn path of justices before her. President Trump nominated her to the Seventh Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals on November 2, 2017. She was then nominated to the Supreme Court, just under three years later, on September 26, 2020. Chief Justice Roberts, nominated by President George W. Bush to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals similarly had a several year stint as an appeals court judge before President Bush nominated Roberts to the Supreme Court. While it may come as no surprise to see Barrett as the current nominee, the amount of work she was involved in during her limited time on the Seventh Circuit is worthy of study and this article undertakes to do so with a complete sample of decisions in which Judge Barrett was involved. Barrett participated in approximately 622 cases that turned into written opinions or orders over that time across a slew of issue areas. Barrett herself authored over 100 combined majority and separate opinions. *

Seventh Circuit Judges

How can we unpack Judge Barrett’s decision making? One way is by looking at who she judged alongside. Eleven judges sit on the Seventh Circuit along with three senior judges and the occasional district judge sitting by designation. Of the fourteen regular and senior judges twelve were appointed by Republican Presidents while two were appointed by Democrats. We can see the frequencies with which she sat on panels with the other circuit judges below. In parentheses are the judges’ parties of appointing president and the appointing president’s initials.

One way to skim the surface Barrett’s decision making is to see which judges she disagreed with most often. This measure captures either when Barrett dissented from another judge’s decision or when another judge dissented from opinions Barrett authored.

As would be expected from a Republican nominated conservative judge, while Barrett voted alongside Judges Wood and Hamilton, the two judges nominated by Democrat Presidents, third and fifth most frequently, she was on opposing sides of decisions from these judges first and third most of all. Of the sitting circuit judges nominated by Republican Presidents, Barrett was on the opposing side of Rovner most often and of Brennan least often.

Case Area

Following mainly the coding for issue area from the United States Supreme Court Database, Barrett’s cases were coded into general and specific issue areas.** The first purpose of this coding was to observe the split in case type of all of the cases that Barrett helped decide while sitting on the Seventh Circuit.

Like all court of appeals judge, the majority of panels Barrett participated in while on the circuit that lead to written opinions ended up in orders. Most of the orders judges release are in criminal cases and as tends to be par for the course, Barrett ended up deciding more criminal sentencing cases than any other case type. Civil rights cases were the second most common and many of these had to do with prisoners’ treatment while in jails. Interestingly though, when summed up, civil liberties decisions were as common as criminal decisions at 141 apiece.

The specific issue areas that came up next most frequently were trial, relating to procedure, discrimination, generally relating to employment, and immigration related decisions. The five most prevalent major issue areas after criminal and civil liberties were employment with 86 opinions, court procedure with 44 opinions, debt related decisions with 20 opinions, and contract and tort decisions with 16 each.

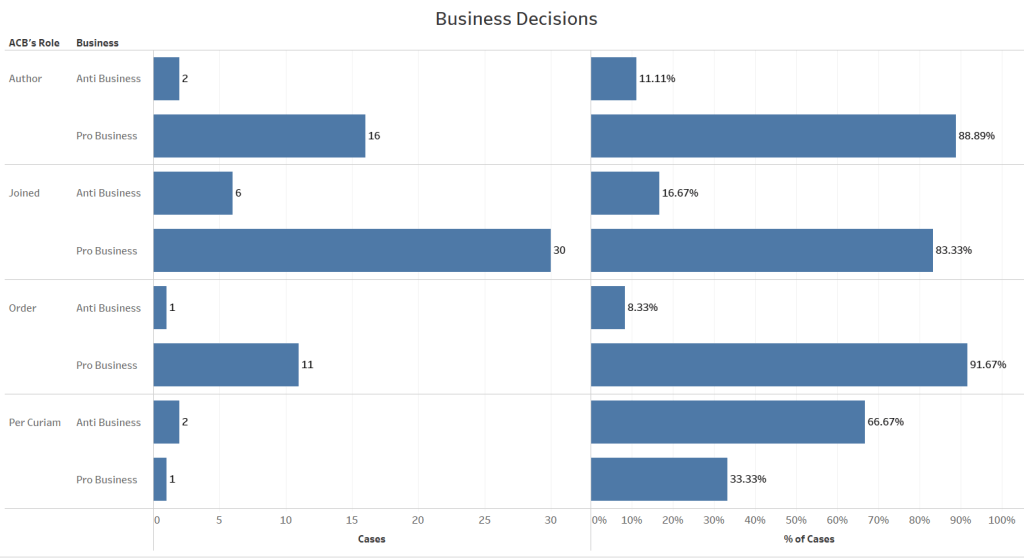

Judge Barrett’s authored and joined opinions and orders in these cases also had and have real world implications. One area that many people are concerned with from a variety of angles is her business decisions. These were coded broadly as decisions affecting business liability, contracts, and deals.

An example of such a decision was in the case Burlaka v. Contract Transport Services LLC where Barrett authored the majority opinion for the panel. Burlaka was a case where, “truck drivers…brought individual, collective, and class action claims against Contract Transport Services (CTS), their former employer, for failing to provide overtime pay in violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which requires overtime pay for any employee who works more than forty hours in a workweek.” The district court in this case, which hinged on whether the drivers were engaged in interstate commerce, ruled against the plaintiff truck drivers. In her opinion, even prior to rendering the decision in the case, Barrett made her position plainly known with the statement, “[t]hese facts plainly demonstrate that at least some spotters drove trailers carrying finalized goods destined for out-of-state delivery. Such a service, even if purely intrastate and interrupted briefly, would nevertheless constitute ‘driving in interstate commerce’ because it would be part of the goods’ continuous interstate journey.” This case presents a clear example of one of Barrett’s pro-business decisions where she ruled against the employees and in favor of the business entity.

Decisions were coded as pro-big business when the business entity was the clear victor or when a large corporate entity was successful in litigation against a much smaller business entity. Barrett’s decisions in this domain were split into opinions she authored, joined, unsigned orders, and unsigned per curiam opinions.

Barrett was pro-business on the balance in all opinion types with frequencies ranging from 67% pro-business to 92% pro-business. This puts her in similar territory with many of the current Supreme Court Justices. Conservative judges tend on the balance to rule more frequently in favor of big business, although the rationale for this differs a bit between Supreme Court and court of appeals judges. On the Supreme Court there is more gray area due the many cases petitioned to the Court and the justices’ wide discretion as to what cases they hear. Conversely, court of appeals judges hear many more cases on mandatory appeals and a larger number of decisions are affirmed based on the lower court’s decision. This fact along with the percentage of Republican nominated judges on the Seventh Circuit might well affect Barrett’s high likelihood of ruling in favor of big business.

Decision Direction

A lingering question on many peoples’ minds is if Barrett is confirmed, where will she fit on the Court? Of course, some of this is beyond the reach of empirical methods. Research has gone into how circuit court judges may alter their decision making in hopes of becoming elevated to the Supreme Court. The bulk of cases at the Supreme Court also differ in a variety of ways from circuit court cases. Finally, circuit court judges are constrained by precedent in ways that Supreme Court Justices are not.

Even accounting for these differences, some have tried to bridge ideology between Supreme Court and appeals court judges using a variety of methods. The truth is that we can’t really know where Barrett would fall on the Supreme Court before she gets there because of the different voting incentives and constraints between the two court levels. We can, however, analyze Barrett’s ideological trends on the Seventh Circuit by measuring the decision direction of her votes. The United States Supreme Court Database has developed a measure for decision direction that can and has been imputed to Judge Barrett’s votes on the Seventh Circuit for this purpose.**

This coding provides a discreet means to look at decision direction by focusing on the issue area, litigant type, and judge’s vote. To give some background on the coding decisions, in the areas of criminal procedure, civil rights, First Amendment, due process, privacy, and attorneys, a vote is coded as liberal if it is pro-person accused or convicted of crime, or denied a jury trial, pro-civil liberties or civil rights claimant, especially those exercising less protected civil rights, pro-child or juvenile, or pro-indigent (among other things). In cases dealing with unions and economic activity a vote is coded as liberal if it is pro-union except in union antitrust where liberal is coded when a vote is pro-competition, pro-government, anti-business, anti-employer, or pro-competition. Some cases do not fall neatly into these ideological bins though and so they remain uncoded along this dimension.

An example of an outcome coded as a “conservative” ruling comes in Shakman v. Clerk of Circuit Court of Cook Cnty. where Judge Barrett authored an opinion dismissing a suit by a union for lack of jurisdiction because the union did not intervene to acquire membership into the plaintiff class. Conversely, Barrett authored an opinion coded as a “liberal” ruling in United States v. Watson, where she held that an anonymous tip did not establish reasonable suspicion sufficient for the police to conduct a Terry stop.

We can look at Judge Barrett’s ideology from several perspectives. One perspective is to see if Judge Barrett’s ideology is consistent when she is the opinion author, when she joins an opinion, and when an opinion is unsigned.

Judge Barrett is most conservative in cases with unsigned orders. This is consistent with existent theory that judges issue orders in cases where there is not much dispute about the outcome and oftentimes these decisions are summary or near summary affirmances of lower court decisions, and primarily in criminal cases. As these “easier” decisions are often in cases where the evidence clearly shows the guilt of the accused and thus is in favor of the state or federal government, the outcome is generally coded as “conservative.”

Notwithstanding the orders though, Judge Barrett shows a high rate of ruling for conservative outcomes in all types of decisions in which she is involved. This across the board conservatism was likely a convincing factor in her nomination, even if this conservatism was measured qualitatively rather than through statistical inquiry. In essence then, this quantitative endeavor either supplants or at least helps to buffer the image of Barrett as a steadfast conservative vote on the Seventh Circuit.

The data on Barrett’s decision making can be observed from different perspectives as well. An important way to assess how she might judge as a Supreme Court Justice is through breaking down decisions into their constituent issue areas. The following figure looks at the ideological directions of Judge Barrett’s decisions broken down by major issue area.

While several of the issue areas only hold a handful of cases, the areas on the top of the figure cover a multitude of cases and all point towards a similar ideological valence. In issue areas with five or more cases, Judge Barrett voted at least 75% of the time in the conservative direction. In contract and IP cases, Barrett’s decisions were 100% conservative. Of the areas with five or more cases, the only area where she voted under 80% in the conservative direction was in civil liberties cases where her percentage of conservative votes was 76.12%. If Barrett is confirmed and remains consistent in her votes as a Supreme Court Justice, we can expect her to line up with fellow conservative justices appointed by Presidents Trump, George W. Bush, and George H.W. Bush.

Judge Barrett was tapped for President Trump’s third nomination to the Supreme Court because of an assessment of her decision making among other characteristics. Other telling studies of Judge Barrett’s decision making look at handfuls of cases and are thus limited mainly to the opinions she authored. The data for this article encompass all of Judge Barrett’s decision and give a novel quantitative picture of her decision making and ideological proclivities. The findings above reinforce the view that Barrett has been a consistent conservative vote in the Seventh Circuit, but also display the range of decisions she was involved in, and the composition of the panels with which she was engaged in decision making. The Judge Barrett Dataset on which this article was based will also be made available on EmpiricalSCOTUS.com prior to Judge Barrett’s confirmation hearings.

* Cases are based on distinct opinions. The counts in this article and dataset differ from those on the Seventh Circuit website as those are based on dockets and thus provide duplicate opinions when one opinion resolved multiple docket entries.

** A sample of 30 cases was used to test for the reliability and validity of the coding through an intercoder reliability test. Professor Jordan Carr Peterson of North Carolina State University was the second coder in this endeavor. The similarity in coding for 219 data points in this 30 case sample was 98.6%. A kappa test for intercoder agreement showed with the highest significance level that we can reject the hypothesis that coding choices were determined randomly.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

5 Comments Add yours