The Supreme Court was not always the powerful institution is it today. The original lack of power was part of the Court’s institutional design. Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federal Paper #78, “…the judiciary is beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of power; that it can never attack with success either of the other two; and that all possible care is requisite to enable it to defend itself against their attacks. It equally proves, that though individual oppression may now and then proceed from the courts of justice, the general liberty of the people can never be endangered from that quarter; I mean so long as the judiciary remains truly distinct from both the legislature and the Executive.”

The power of judicial review as set out in Marbury v. Madison started to change this process but it wasn’t until much later that the institutional power of the federal courts began to pick up steam. The Court, for instance, did not hold a federal statute unconstitutional until fifty years later in the Dred Scott decision of 1857. It was only then that the Court began to flex this power.

Practices of the early Court similarly did not parallel those of today. Justice Rehnquist discussed the evolution of Supreme Court practice in his article From Webster to Word-Processing: The Ascendance of the Appellate Brief. Rehnquist described, “When, in 1821, the Supreme Court for the first time required the parties to submit a brief, it was not anything like the brief that we know today.” He then wrote that it wasn’t until 1884 that the Court mandated briefs include a party’s arguments.

This history of the Court suggests that the Court’s historic output should not have been as pronounced in the early Court as it is today. It further suggests that the inertia that the Court picked up over time should continue to accumulate as the Court becomes more of a centerpiece in modern day politics.

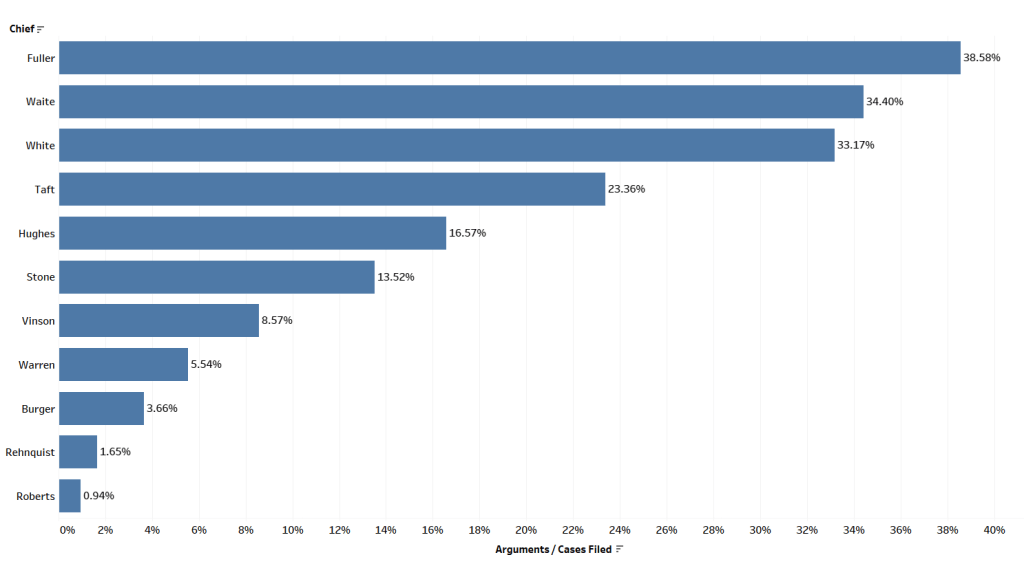

In fact, from chief to chief justice, the Court has heard an ever decreasing percentage of cases on oral argument based on all the cases filed to it since 1880 except in one instance (the Fuller Court heard a greater percentage of cases filed than the Waite Court). The Federal Judicial Center provides Supreme Court filing statistics between 1880 and 2017. The following graph shows the average percentage of oral arguments divided by cases filed to the Supreme Court by chief justice going back to the 1880 term.

Since the number of oral arguments has dropped since 2017, presumably the Roberts Court’s average is even lower than that shown in the graph. The Court’s lack of productivity is also evident in the following graph (based on cases orally argued derived from the Supreme Court Database) showing how it hit a modern day low last term when the Court decided the fewest number of cases on oral argument since the Civil War.

Based on the historical evolution of the Court’s institutional power and legitimacy, the Court’s diminished modern day merits docket implies that not only is the Court less productive now than it was before, but that it currently may be the least productive Court ever. There was no expectation that the Court would decide a baseline number of cases each term in the mid-1800’s. Once the Court began hearing 150 to 200 cases a term in the mid-20th century though, the expectation became that the Court would continue to do so. Obviously, the Court has not followed this course.

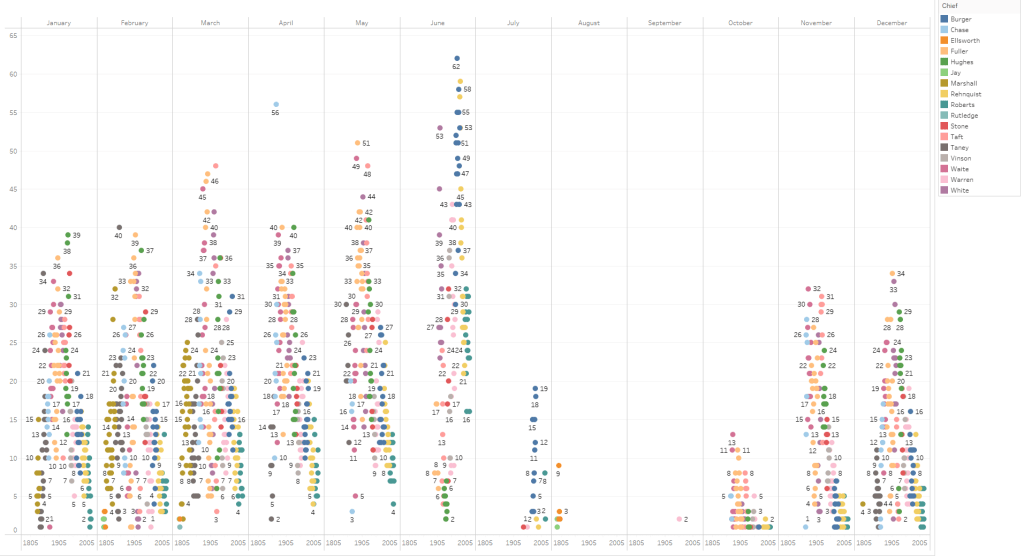

We can see this declined productivity on a monthly basis as well. The following graph depicts the decisions rendered in each Court Era (defined by chief justice) by month.

Many of the high watermarks were from the Burger Court in the month of June. The Chase Court exceeded all other Courts in the month of April with a 56 decision month. The Roberts Court tends to be consistently on the low end of monthly output compared with other Court Eras.

This has led to a unique artifact of decision making this term. Greg Stohr of Bloomberg recently employed my data to show that the Court’s caseload in June of this term is the highest percentage of the Court’s caseload in the final month of the term since at least 1950 (in a few instances the Court has delayed releasing a few decisions until after June). Since the Court’s calendar running from October to June started in the 1916 term I ran the analysis back to 1916 and found that the highest previously backlog in orally argued cases since that term and preceding the current term was in the 1975 term when the Court still needed to decide 51% of its argued caseload by June.

With 53% of cases undecided by the beginning of June 2022, the Court has had its least productive term through the second to last month of a term since the Court’s calendar moved to October through June.

Other indicators similarly reflect the Roberts Court’s lack of productivity. Based on the preceding graphs it should not be surprising that the Court’s current majority opinion output is the lowest it has been since the Civil War. The following graph shows the average annual number of majority opinions in orally argued cases released by Court Era.

The only Courts that were less productive than the Roberts Court were under four of the first five chief justices. The only reason that Rutledge, the second Chief Justice, is not on this graph is that he only served in this role from August through December of the 1795 Term.

The argument that the current justices’ secondary opinion output makes up for the shrinking overall caseload similarly lacks a foundation. If we look at the overall number of majority and secondary written opinions in orally argued cases by Court Era, the bottom of the graph is practically unchanged from the prior graph.

This graph shows that the Roberts Court has been more productive than the first six Court Eras, the latest of which ended in 1873. Based on the notion that the Court was still developing a more extensive caseload during these years, the Court’s current output is still arguably at an all time low.

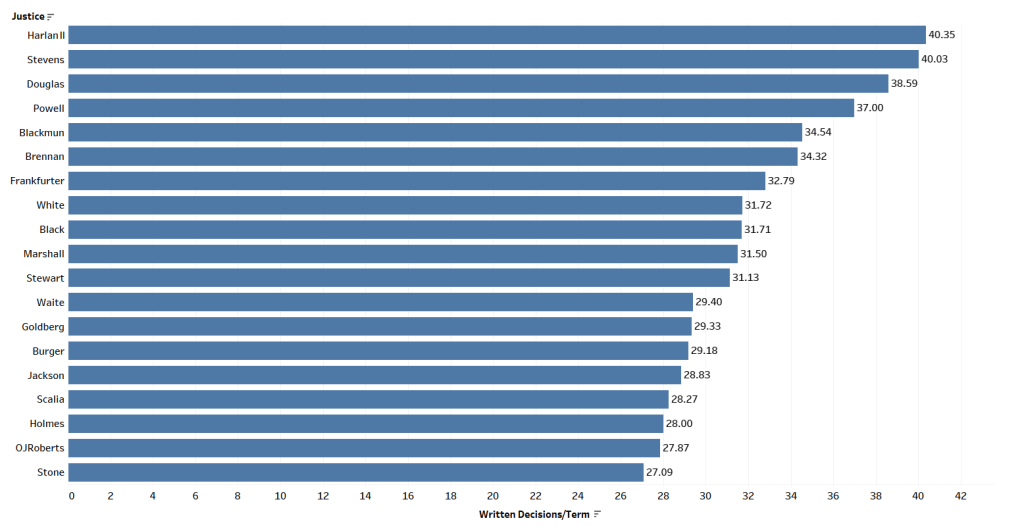

A third measure further highlights the current Court’s lack of productivity. Looking at overall output per justice we find that none of the top 20 most productive justices by annual opinion output (majority and secondary written opinions in orally argued cases) currently sits on the Court.

This is, however, the most promising graph for the current Court’s production. Justice Stevens, the second most productive justice by this metric, sat on the Roberts Court from 2005 through 2010. Justice Scalia, also a member of the Roberts Court for several years, is on this graph as well. The other 18 of the top 20 most productive justices based on written opinions per term, however, did not sit on the Roberts Court.

The Court has drastically changed its shape over time. The justices are deciding some of the most politically charged and publicly important cases ever this term, dealing with issues such as abortion, gun control, and border policies. On the other hand, the Court only heard 63 arguments this term which is below the average number of arguments even during the Roberts Court years. The graphs above convey that this Court’s current productivity is the lowest that it has been since the 1800s and since the Court was only in a nascent stage at that point, the Roberts Court is arguably the least productive Court in history. This trajectory is unlikely to change anytime soon.

Based on the number of cases the Court has granted so far for the 2022 term, we should not expect a dramatic uptick in the number of oral arguments. Similarly, based on the Court’s recent history, its overall productivity is only likely to shrink even further in future years. There is also little evidence that the justices intend to take a diminished role in American politics by deciding less politically charged cases. Since the justices are appointed for life, there is little that external actors can do to change these patterns. Thus, the public can only watch from afar as the justices carve out their ever-changing roles in the federal government and in American politics.

Find Adam on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

22 Comments Add yours