This Supreme Court term was nerve racking for some conservatives (mainly unwarranted), most liberals (with good reason), and probably for some of the justices too, and yet all for different rationales. Below I’ll go through what may have caused this tension and why members of these three groups might have felt it.

Before the Court’s decision in the Travel Ban case, Chief Justice Roberts authored 16 majority opinions in his career on the Court where the justices split their votes 5-4. The only other such case this term was Carpenter where, like in Trump v. Hawaii, the Court’s conservative majority was pit against the Court’s liberal minority. Roberts aligned with the four liberal justices on the Court in only two of these decisions across his tenure on the Court – in Williams Yulee v. Florida Bar (2015) and in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012). Interestingly, in two of Roberts major decisions on executive power, NFIB v. Sebelius and King v. Burwell, Roberts also aligned with the liberal justices.

These past cases provide some insight that Roberts does not want to be viewed as partisan in his decisions affecting the executive power. Nevertheless, the Roberts majority upheld the travel ban against the dissents of the Court’s liberals. This division in the Court was especially pronounced in Sotomayor’s 28-page dissenting opinion which concludes,

“Our Constitution demands, and our country deserves, a Judiciary willing to hold the coordinate branches to account when they defy our most sacred legal commitments. Because the Court’s decision today has failed in that respect, with profound regret, I dissent.”

Roberts is a conservative justice. This is apparent from the Court under his watch generally, as well as from his support for traditionally conservative agenda items. With these ideological bearing in mind Roberts may have still agonized over the split vote and outcome in Trump v. Hawaii. Why? As much as Roberts has his leanings, he seems to want to avoid the perception that his Court is entrenched in politics. 5-4 splits along partisan lines in politically charged cases directly implicate politics in the Court’s decision making.

This partisan split on the Court though was a recurrent theme this term. 13 of the 18 decisions that split the justices votes five to four were decided by the five more conservative justices in the majority. As Kennedy did not side with the more liberal justices once in such decisions this term, the conservative justices found themselves time and again in control of majority opinions. This disparity in voting was actually unique for Kennedy in the Roberts years for cases. The graph below shows the number of times Kennedy aligned with the more liberal and more conservative coalitions in 5-4 decisions since Roberts joined the Court in 2005.

As the graph above shows, this is the only term in the Roberts years where Justice Kennedy did not align with the liberal coalition at least once in a 5-4 decision. Also unlike in previous terms where Kennedy wrote majority opinions in most of these 5-4 ideological splits, Justice Gorsuch wrote majority opinions in five such decisions this year compared to Kennedy’s one (Kennedy had a second 5-4 decision in Wayfair but in that case Roberts dissented and Ginsburg was in the Court’s majority).

This provides context behind why the more liberal justices on the Court so often dissented in 5-4 decisions this term. It also provides some of the buildup behind why this has likely been such an exhausting term for Roberts. Not that Roberts didn’t agree with the decisions. Roberts was in the majority in (16) of the (18) 5-4 decisions, only dissenting in Wayfair and Dimaya.

As Professor Maya Sen spelled out and I’ve said in the past, Roberts is extremely conscious of Court’s image and institutional standing; perhaps more so than his predecessors. The conservatives’ edge this term has been attributed many times to Senator McConnell’s maneuvering during the Scalia vacancy (McConnell did little to mollify this perception as after the decision in Trump v. Hawaii was released he tweeted a picture of himself with Gorsuch). If Roberts wants the public’s perception of the Court free from concern that politics is playing a lead role in decision making then such photos and the disproportionate voting splits favoring the conservatives may not necessarily be an entirely favorable scenario in his eyes.

This image problem may well have led to the Court’s slow pace in releasing decisions this term. Below is a look at the average time between oral arguments and decision by term since before the Congress made certiorari the main mode of getting cases to the Court with the Judiciary Act of 1925.

As the graph makes clear, the average pace this term was slower than in any year since before the Act passed in 1925.

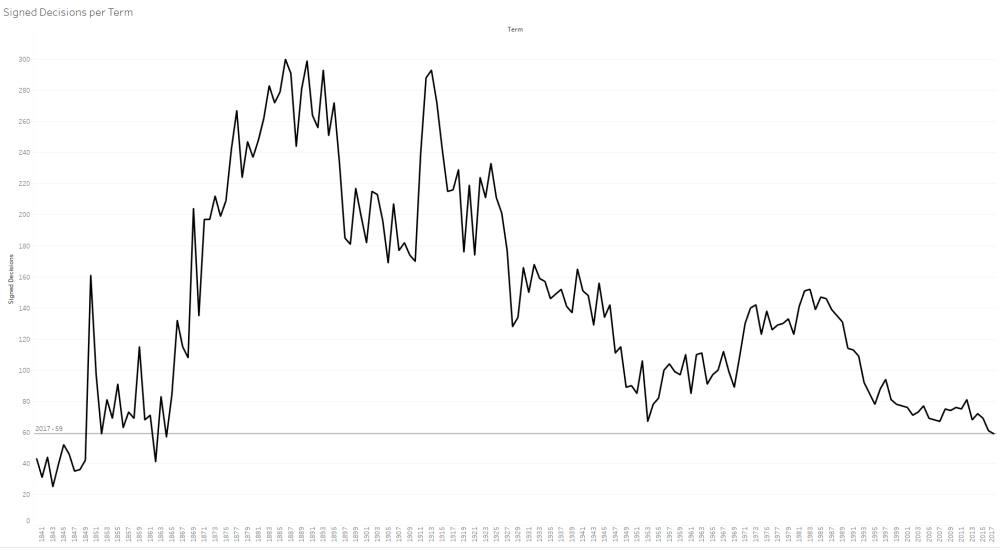

The Court, however, decided fewer cases this term by signed decisions than it has since the Civil War as the next graph shows.

At first blush, some might assume that with such a light caseload the Court would render decisions more efficiently than in the past. Here is where the gravity of the decisions and the voting splits may have had their greatest impact.

If justices, and Roberts in particular, wanted either resolution in cases or to avoid 5-4 ideological splits then the perhaps much of the time the justices took deciding cases this term was due to posturing and correspondences in hopes of securing larger and more diverse majorities. This was likely only compounded by the time it took the more liberal justices to author dissents in all of these close decisions.

The following figure provides further evidence that the Court was dilatory in releasing its opinions compared to years past. On the top it shows the percentage of cases by term that the Court decided in the last two months of the term compared to the cases decided at any other time during the term. On the bottom the bars show the raw counts behind these percentages.

At 63%, the Court decided a greater percentage of its cases at the end of this term than it has it has since at least prior to 1870.

The case that took the justices the longest to decide was Gill v. Whitford which at 288 days pushed towards the upper limit of time the Court has taken to decide a case since Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1925.

While Gill was a unanimous decision, the case itself didn’t resolve very much as the opinion focused on the plaintiff’s lack of standing and not on the case’s merits. Based on the tenor of the term, this decision, similar to many others this term, may have taken a good deal of time to release not because of the difficulty in crafting a decision, but rather the difficulty in finding a majority of justices to support a particular position. If Roberts were looking for a means to avoid another 5-4 ideological split in case with extremely political dimensions then the outcome in Gill at least may have been a welcome compromise.

The Supreme Court’s recent history is riddled with divides between the Court’s right and left and this is one of the most divided Courts we have seen in a long time. Now with the announcement that Justice Kennedy is retiring, this division will inevitably become exacerbated before it wanes. The stakes involved in the upcoming nomination have striking implications. Unfortunately for the Court’s liberals, there is little hope of a shift in the Court’s median direction to the left in the years to come. These ideological splits will become more pronounced as the conservative justices realize that they can select cases in hot-button issues with a coalition to move policy in a preferred direction. Unfortunately for Roberts, this will only increase the commentary of the political nature of the Court, something Roberts has tried to avoid for over a decade now. Roberts may not be able to avoid having his legacy wrapped up these views of the Court but he might not be too terribly upset about the Court’s rightward policy momentum that gained increasing steam this term.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

8 Comments Add yours