While most of the Supreme Court’s notable matters include cases with far reaching implications that are decided with written decisions, some of the most important decisions the Court makes have to do with emergency matters that are time-sensitive. The Court examines a number of stay applications each year, which are typically dominated by capital cases. Since the death of Justice Scalia and the change of the Court’s composition, the allotment of circuits to the Justices for stay applications has shifted. While Justice Scalia was previously responsible for applications from the Fifth Circuit, now this is Justice Thomas’ responsibility.

Along with the shift in responsibility, the shift in the composition has a subtle effect on the Justice’s behavior in matters relating to stays or injunctions. Since the Supreme Court requires a majority of Justices to grant a stay, without Justice Scalia the likelihood of a grant diminishes. This is especially so for the more conservative Justices. By contrast, since a majority is required, the ability for the four more liberal Justices to achieve a majority is not enhanced and will not be enhanced unless a more liberal Justice is subsequently added to Justice Scalia’s seat.

The effect of this shift is evident in the Court’s recent decision on North Carolina voting rights where the Court was split ideologically, and where the conservative Justices would have likely blocked the stay with the additional vote of Justice Scalia. How significant is the shift in the Court’s behavior? This is the question I tackle in this post by looking at the 24 decisions on stays since Justice Scalia’s death and the 24 decisions before Justice Scalia’s death (for recent orders of the Court see this link). For the purpose of this post and to get the count of 24 stay decisions I combined dockets related to the same underlying case.

The Court tends to grant a low, although not insignificant number of stay applications. There is no reason for this rate to increase without Justice Scalia. But there are apparent, albeit subtle, shifts since Justice Scalia’s death, some of which are related to the Court’s composition while others to the type of matters before the Court. The first two figures show the allotment of petitions by Justice/circuit.

In both situations the majority of applications were before Justice Thomas. As might be expected, after Justice Scalia’s death, Justice Thomas handled the exact number Justice Scalia handled in the previous 24 instances in addition to the same number he handled previously.

Also as might be expected, the grant rates did not dramatically shift in these two period.

The only shift in grant rates between the two periods stems from one additional grant and one fewer denial in the post-Scalia period.

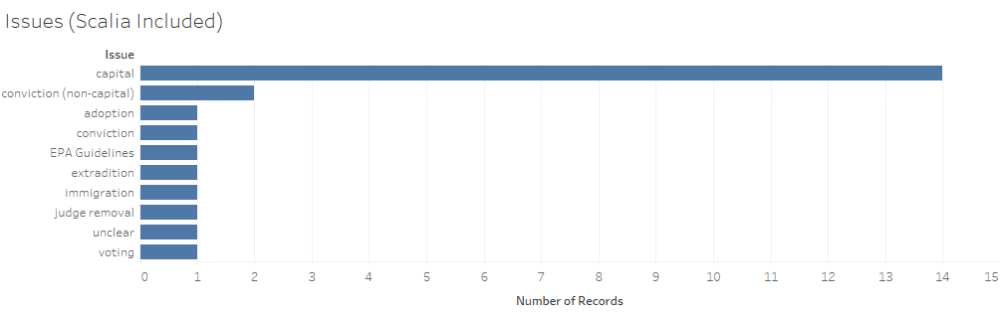

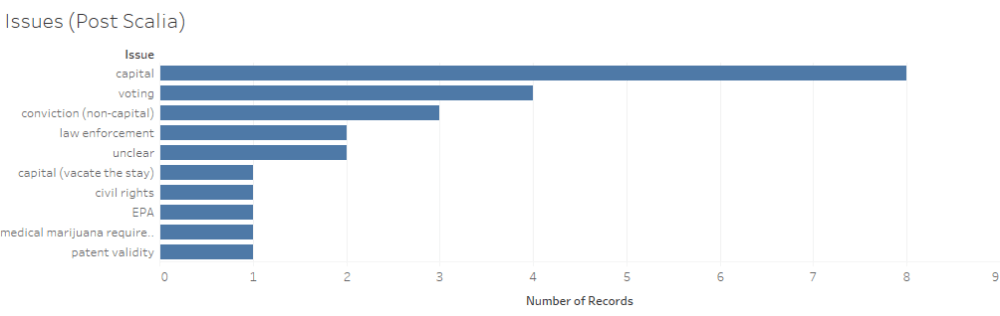

While capital cases dominated the stay applications that the Justices handled in the two periods, there is an apparent difference in the types of matters the Justices handled. This, however has little to do with Justice Scalia’s presence on the Court as the next two figures convey.

[* In one habeas case the stay did not relate to a potential execution although the crime was capital in nature and therefore I did not code it directly in the capital or non-capital categories.]

There are a variety of issues that the Court tackles with these applications ranging from the requirements for obtaining medical marijuana licenses to the removal of judge from a state bench. The main difference, with the national election imminent, is that the number of applications in voting rights / redistricting cases is clearly on the rise.

Another clear difference between the two periods that may directly relate to the loss of Justice Scalia has to do with the Justices’ separate opinion in such matters. After Justice Scalia passed, the only separate opinion relating to a capital stay application was Justice Breyer’s dissent in the case Conner v. Sellers (16A58, 16A59) and this dissent was a short paragraph (the only additional separate opinion in a non-capital matter during this period esd Justice Breyer’s courtesy concurrence in the transgender bathroom case, which had no impact on the ultimate decision although the move was scrutinized for its symbolism). By contrast Justice Sotomayor had two concurrences and one dissent in such capital matters in the period including Justice Scalia and Justice Breyer had three dissents. Perhaps with an expectation of a shifting majority’s view regarding the death penalty, the liberal Justices feel less compelled to write separate opinions if the purpose behind them was to build future coalitions, and instead they await the outcome of the nomination (some of the implications of the shifts in the Court including views on the death penalty are described in this piece by Michael Dorf).

In addition, there are the direct changes that can be ascertained as a result of the loss of Justice Scalia. Although the Justices tend to mask their votes in these matters, they do broadcast them in limited instances. One instance as discussed above is in the recent decision affecting North Carolina voting rights. There almost certainly would have been a different result with Justice Scalia on the Court. In another case, Dunn v. Madison, the four post-Scalia conservative Justices would have granted an application to vacate the stay in this capital case but were unable to do so without a fifth, majority vote.

In a series of applications that Scalia voted on relating to EPA measures, the four liberal Justices would all have voted to deny the application. The application would have been denied if it was dealt with after Justice Scalia’s death, but with Justice Scalia on the Court, the conservative Justices were able to vote ideologically and grant the stay.

These may be the most direct changes that have resulted from Justice Scalia’s death in these cases, yet we are sure to see more clear and nuanced changes as the Court handles more such applications. There will also be a further shift in behavior with the addition of a new ninth Justice although the shift is only predictable to the extent that we understand the likely voting behavior of Justice Garland or any other nominee (liberal or conservative) that is confirmed as the next Justice.

Empirical SCOTUS updates on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman; Facebook Empirical SCOTUS

Data derived from case specific queries via LexisNexis and the Supreme Court’s website.

2 Comments Add yours