While few people ever have the opportunity of sitting on the Supreme Court, some similarities exist between this upper echelon of judging and other jobs. One parallel has to do with job satisfaction. While judges that make it all the way to the Supreme Court should feel accomplished and contented by their achievements, there also must be at least a continuum of job satisfaction among the justices. That is not to say that any justice necessarily dislikes the job, just that they may not equally enjoy it either. Measuring job contentment in such a profession without first hand anecdotal evidence is tricky at best. One thing we do know about the justices though that might very well relate to satisfaction is how often they vote in the Court’s majority or conversely, how frequently they are in dissent.

Historically, justices have been in the majority across entire Supreme Court terms. At very least this shows that they were in sufficient agreement with the other justices that they did not perceive the need to voice antipathetic sentiments. There have also been terms where justices have dissented in nearly half of the cases the Court heard argued. This discord with the decision-making engine of the Court could well breed frustration with those more often in the majority (note that this is not the only explanation for dissenting behavior). For instance one of the Court’s most frequent dissenting justices of past, Justice Douglas, was described by a former clerk as “a very unhappy man.” The Court’s most prolific modern dissenter, Justice Thomas, has also made some waves with positions he advanced in recent cases.

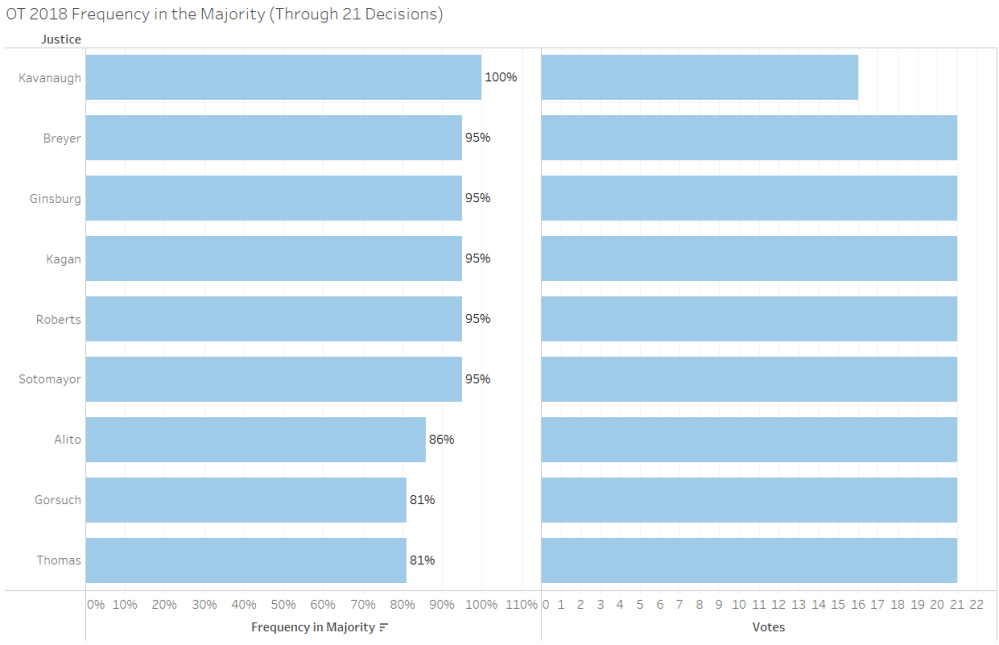

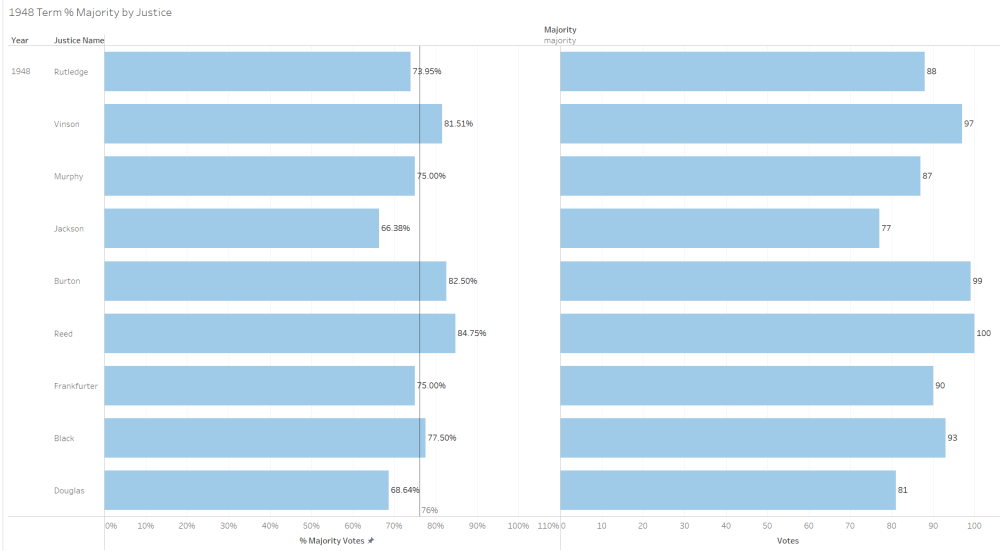

Justices typically vote in the majority much more frequently than these two outlying justices. So far this term the justices’ frequencies in the majority range from 81% to 100% (frequency in the majority in the graph below is shown on the right and the number of votes composing this measure is shown on the left).

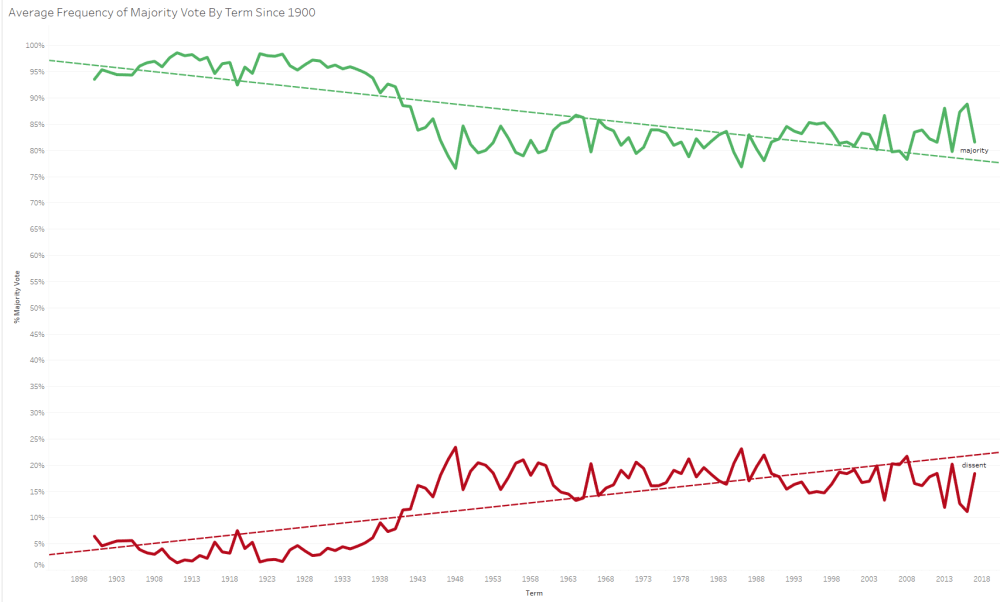

How does this stack up to justices in years past? In recent terms justices have ranged from 97% frequency in the majority (Kennedy in OT 2016) to 61% in the majority (Thomas in OT 2014). While Kennedy’s 97% is quite high, and the justices still often reach many unanimous decisions every term, justices now typically don’t vote in the majority as frequently as they did in past. When we look at the justices’ frequencies of voting in the majority in argued cases since 1900 we see a clear dip over time.

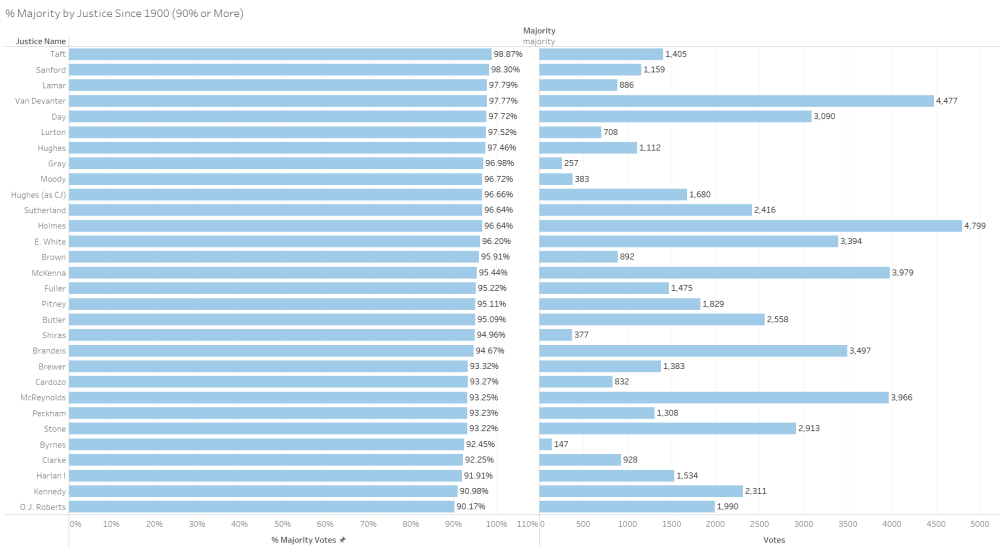

Whatever led to the past high level of consensus no longer holds quite as true. This is particularly evident when look across justices’ career votes. When we look at justices that voted in the majority at least 90% of the time through their careers since 1900, Kennedy is the only modern justice that makes the list. In fact, aside from Kennedy all of the justices that made this list sat on the Court prior to 1950.

Several reasons likely exist for the differences in frequencies in the majority from past terms to now. Along with the past norm of consensus, the justices may not have had as complex and divisive cases in past when much of their jurisdiction was mandatory. In past the justices have voted almost unanimously across entire terms. The highest average frequency in the majority across the Court in a term since 1900 was in 1911 when the average frequency in the majority was 98.3% (averages are shown in gray lines overlaying the bars).

Justice Day’s 100% frequency in the majority was not even entirely unique as several justices had this high a frequency for a term in the same era. The closest the Court has come to this level in recent years was during the 2016 term (the term where Kennedy was in the majority 97% of the time).

One caveat to this figure is that this high level of consensus may have had to do with the composition of primarily eight justices as Gorsuch only sat on the Court for the April oral argument session. Still, when we focus on the years since Roberts took over the post of chief justice, we see a consistent average frequency in the majority across justices of 80% that even rises a bit from 2005 through 2017.

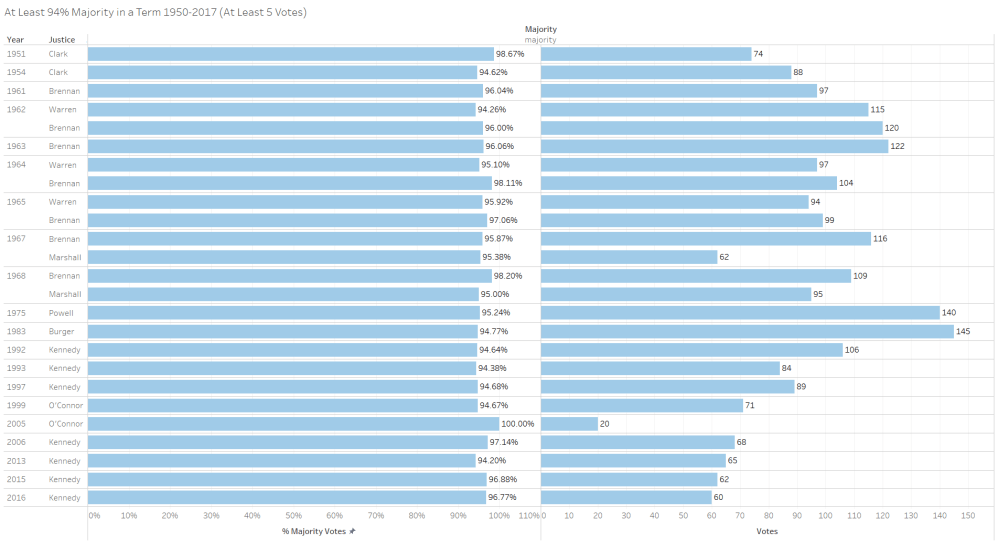

Justices are typically much more often in the majority than they are in dissent, even in recent years. Kennedy’s high frequency is still an anomaly though. His role as swing justice may well have contributed to this. When we look at justices that have had a frequency in the majority of at least 94% for a term since 1950 (with five votes or more in a term) we see the only two justices from recent Courts were Kennedy and the other swing justice of recent years, O’Connor.

Interestingly, while the Court is well known for its conservative majorities, the instances in this chart where two justices had frequencies in the majority of 94% or more in the same term were all permutations of the liberal justices from the Warren Court years – Warren, Brennan, and Marshall.

Justices at the opposite end of the spectrum tend to cluster together as well. When looking at the lowest frequencies in the majority by term since 1900, justices from the Vinson Court (1946-1953) take the cake. The lowest overall average frequency in the majority for a term since 1900 was in 1948 when the justices voted on average 76% of the time in the majority.

Several of the justices that term had frequencies below 70% with Justice Jackson the lowest at just over 66%. Justice Douglas had the lowest frequency in the majority across an entire term though with his 49.51% in 1952. When looking at the frequencies across justices for the 1950-1952 terms, we can see quite a considerable difference from the high frequencies profiled earlier in this post.

Looking at justices with the lowest career average frequencies in the majority paints somewhat of a different picture. Rather than featuring predominately Vinson Court justices, many of the justices with career lows are actually from the current or recent Courts.

Some of this may have to with the fact that current justices’ averages, especially Gorsuch’s, are based on typically a smaller sample of votes and are to this point incomplete. That said Justices Stevens, Rehnquist, Souter, and Scalia all left the Court after the year 2000 and are on this list. Also, Thomas’ and Ginsburg’s frequencies are based on over 1,000 votes apiece. This hints at the significance of the decline in the overall average frequency in the majority by term since 1900 as depicted in the second figure in the post.

A question that this decline in average frequency in the majority begs is whether this trend will continue. While the numbers for the 2018 term do not hint at this so far, they are unlikely to continue like this for the remainder of the term. First off, the justices tend to hear more divisive cases later in the term. That is where we tend to see the bulk of 5-4 splits and many of resounding decisions from recent terms (think Obergefell, Hobby Lobby, Fisher, etc.) Secondly, the Court is potentially ideologically split like never before. Although Roberts has done a good job of uniting in the Court’s more conservative and liberal wings in the Court’s argued decisions so far this term, inevitably we will see many more fractured decisions which will be quite telling of the future direction of the Court.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

Also can be found at Optimized Legal

Post includes data sourced from the Supreme Court Database

Looking at the first chart of average votes in the majority per term, it seems like instead of a linear regression of constantly increasing dissent from the majority over time, a better model might be relative stasis from 1900-1935 and 1945-present with some sort of equalibrium shift during those 10 years. In other words, it seems like if you only count the last 75 years, the frequency of majority vote has been stable at 80-85%

LikeLike

Good point. This looks correct from the data and makes sense based on the notion that ideology as we know it today really started to kick in around the time of the Vinson Court.

LikeLike

I believe you’ll find that rather than “the justices tend to hear more divisive cases later in the term,” they tend to issue more divisive opinions later in the term because it has taken longer for the drafts to circulate among the chambers, the justices to negotiate wording for the majority or plurality opinion and the clerks to prepare dissents. The cases are heard throughout the term interspersed with less controversial cases.

LikeLike