While Supreme Court Justices’ votes are not purely the product of ideological preferences, some of the most important cases the justices decide come down to 5-4 splits along ideological lines. This was especially apparent during the 2017 Supreme Court term. Even though Chief Justice Roberts was in the conservative camp for many of these split decisions last term, he voted with the Court’s liberals in Artis v. District of Columbia and authored the majority opinion which was joined by the Court’s liberal justices in Carpenter v. U.S. At the end of the term when Justice Kennedy departed the Court, most Court watchers were betting that the Court’s ideological center was shifting to the right leaving Roberts as the conservative median justice.

Then came a shock when Roberts sided with the Court’s liberals in several instances at the start of the 2018 term, and so it seemed that those past votes with the liberals may been more than mere aberrations. What was the cause of this? Were these instances other anomalies? Is this another case of ideological drift? Or maybe the Court’s conservative momentum has pushed it to the right of Roberts’ preferences. Some statistics help to disentangle this ball of yarn.

The Supreme Court Database provides coded case level data for Supreme Court decisions through the end of the last term. The Database’s coding rules specify that decision ideological decision direction coding is based on the issue area and the type of winning party. An example of this is that when a pro-government entity wins in cases coded in the area of unions and economic activity, the outcome is coded as liberal. * Beginning with this data we can assess the extent to which Roberts has moved left versus the Court moving right.

Baseline

To get a sense of ideological movement on the Court, we initially must assess the extent that the justices vote ideologically and if ideology plays a particular role in specific types of cases. The actual ideological split in terms of total decisions by term appears fairly even since before Roberts joined the Court. The top graph below tracks the percentage of cases by term coded as liberal and conservative decisions while the bottom graph shows the raw numbers of decisions.

This evenness becomes more skewed towards the conservative direction when we look at decisions by a single vote margin.

Neither of these graphs show a drastic trend towards the right over the Roberts Court years although the Court has moved in this direction over the past two terms. When we look at the proportion of votes aligned with the ideological direction of the Court’s majority, we do see a subtle increase in conservative vote share in conservative decisions since Roberts took over as Chief Justice.

The same cannot be said for liberal votes in liberal decisions although this trend has steadied over recent years. This might relate to more closely divided cases as of late.

The Supreme Court Database also breaks cases down by their issue areas. When looking at this breakdown, we see that the Court has been balanced or moved in the liberal direction in all areas aside from judicial power and unions. This movement towards the liberal direction began with baselines that favored conservative outcomes. The top graphs show the proportion of liberal and conservative votes while the bottom shows the count values for the cases making up the percentages above.

Thus far according to these measures the Roberts Court appears to have decided cases fairly neutrally with respect to ideological direction. Although on the balance the Court’s decisions appear to slightly favor conservative over liberal outcomes, this trend appears to have diminished in recent terms (note that there are no major differences in these trends if we push back as far as the 1980 term with the possible exception of economic activity which has slightly trended right over time).

Conservatives

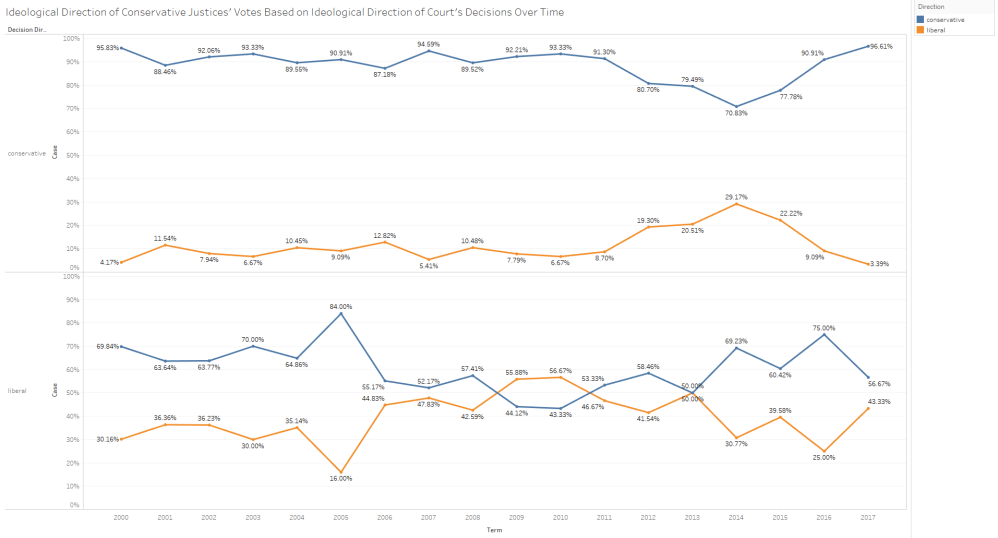

Next we can look to see if the Court’s conservative majority moved farther to the right since Roberts joined the Court. This supposition has some anecdotal support as the biggest ideological shift during this period due to a justice’s retirement occurred when Justice O’Connor retired and was replaced by Justice Alito. The following graph tracks the voting direction of the more conservative justices — Alito, Thomas, Scalia, Rehnquist, and Gorsuch — between the 2000 and 2017 terms in cases split between instances where the Court ruled in the ideologically liberal and conservative directions.

These data show that in conservative cases the conservatives were fairly consistent in their voting a very high rate in the conservative direction aside from in the 2014 and 2015 terms. The conservatives were, not surprisingly, a bit less consistent with cases decided in the liberal direction. They had two periods, around the 2006 term and between the 2014 and 2016 terms when they voted more conservatively in cases the where the Court’s decision was coded as liberal. This fraction of cases contracted somewhat during the 2017 term although there was a clear ideological divide between the liberal and conservative justices.

We can also look at a particular justice in the conservative camp to see if there were any individual shifts in voting behavior. Focusing on Thomas for this purpose and splitting the cases by the ideological direction of the Court’s decisions, we see a few relevant transitions in his votes since the early 2000’s.

Thomas voted a tad more towards the liberal end of the spectrum in conservatively decided cases between the 2012 and 2016 terms. He also voted a bit more in the liberal direction in the Court’s liberal decisions between the 2009 and 2013 terms. From the 2014 to the present term though his proportion of conservative voting in liberal decisions is back to a similar rate as it was prior to the 2009 term.

Thomas’ voting behavior does not suggest he shifted farther right between 2000 and 2017. The aggregate of conservative justices’ votes though show the possibility of a slight movement to the right, especially in recent years. This shift though seems more of a rebound from a short period of less conservative voting though than a thrust to the right in a manner not seen since before Roberts was appointed Chief Justice.

Roberts

With minimal evidence suggesting a strong conservative push in recent years we now turn to Roberts’ record to see if he pivoted leftward. Roberts has been viewed as a stalwart right winger since he joined the Court in 2005. Although often described as less conservative than his predecessor, Chief Justice Rehnquist, Roberts has tended to side with the Court’s conservatives in most decisions that split the justices ideologically including writing the majority opinion in Shelby County v. Holder, the decision that ruled Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional.

The data bear this profile out to a degree, but also show fluctuations in his voting behavior along with occasional moves leftward. Beginning with a look at Roberts’ votes in cases when the outcomes are coded as conservative or liberal we see a consistent preference to side with the conservatives on conservative issues and a less consistent approach in liberal decisions.

Roberts is predominately in the Court’s majority across all cases. He does this by voting primarily in the conservative direction when the case is a conservative outcome and in the liberal direction when the case is a liberal outcome. There are two dips in his percentage of conservative votes in conservative outcomes but never below the 80% threshold. He also voted over 90% in the liberal direction in liberal decisions in two separate terms. While the line depicting his liberal votes in liberal decisions is much more jagged than his line for conservative votes in conservative outcomes, the liberal line has smoothed over recent years, plateauing at just below the 90% level.

Evidence from the overall direction of Roberts’ votes also suggests the possibility that Roberts has moved leftward over recent terms. The following graph tracks the percentage of Roberts’ votes coded as liberal and conservative on top, and the raw numbers associated with the percentage values below.

Although Roberts began his career on the Court significantly favoring to vote conservatively, this trend diminished over time to the point where in two terms, 2013 and 2014, Roberts actually voted in the liberal direction more frequently than he did in the conservative direction. Since the 2014 term, Roberts’ has voted primarily in the conservative direction, but at a much less aggressive rate than he did earlier in his career. This begins to paint the picture of, at least a less staunch ideologue.

The locus of this transition in voting behavior can be tracked by breaking Roberts’ votes down by individual issue area.

The possibility of Roberts’ liberal progression is evident in his votes in several of these areas over time. His frequency of liberal voting has notably increased in criminal procedure cases, economic activity cases, and in First Amendment cases. His votes do not exhibit a decline in liberal frequency in any of these areas perhaps with the exception of union cases.

The reason for the fluctuation in Roberts’ votes especially in the three areas where his frequency became more liberal over time is better explained when his votes are broken down by the ideological coding of the Courts’ decisions.

As with the earlier graphs, the graphs above show that Roberts predominately votes with the Court’s majority. In the three areas described above — criminal procedure, economic activity, and First Amendment cases – Roberts has voted in the liberal direction more frequently over time in cases where the Court’s outcome is conservative. In criminal procedure cases he also appears to have shifted to voting in the liberal direction more frequently in cases with liberal outcomes over time. For these data to be meaningful though we must at least assume that the number of conservative and liberal outcomes has not dramatically differed over the years and this ratio appears fairly consistent when we look at the count and frequency of decisions in both directions in the top chart in this post.

The results of this analysis show that while the Court’s conservatives may have moved slightly to the right since Roberts joined the Court, Roberts has exerted some clear movement to the left. This of course is based on the assumption that all cases are equal (which they are not). Roberts may be voting conservatively in more important cases and liberally in less important cases, essentially nullifying any evidence of a leftward shift. Some additional perspective can be given by focusing on cases decided by a single vote margin. Here we see probably the most consistency in the graphs analyzing Roberts’ votes.

Roberts clearly favors voting conservatively in all cases decided by one vote outcomes and has predominately voted conservatively in conservative decisions by a single vote (the top row of graphs). He has displayed a balance in voting liberally and conservatively when the Court’s outcome has been liberal. Last term was the first time, however, where Roberts voted more times liberally than conservatively in 5-4 decisions where the Court’s outcome was coded as liberal.

While Roberts is by no means moving into the Court’s liberal camp, the data concerning his ideological voting behavior does intimate a mild liberalizing over time. This seems more likely to be the cause of the observation that Roberts’ is siding with the Court’s liberals more often as of late than the explanation that the Court is itself shifting rightwards, although the confluence of Roberts’ shifting voting behavior and a mild rightward push by the Court’s conservatives could well be the case.

*Data note: The main data resource used in this post is the Supreme Court Database’s ideological coding for decisions. This has both costs and benefits. Decisions were hand coded according to specific coding rules. The measures are fairly reliable and were often coded twice to remove human error. The strict coding rules, however, do not leave much leeway for cases that had a specified ideological outcome based on winning party but did not actually resolve in the noted direction. Take the example of a case where the Court sides with a pro-government entity that supports conservative, big business interests. This is an inherent weakness of the method as this outcome would be coded as liberal based on the winning party. Alternatives measures of ideological outcomes, however, produce less satisfactory solutions. Methods that allow more flexibility at the coding level bring with them the possibility of subjectivity entering the decision frame which would endanger the measure’s reliability. Other more complex, automated methods of coding for ideology using machine learning have not yet proven more useful and accurate. Although this coding is an imperfect science, it is a consistent approach and it provides a reasonable means of assessing the ideological movements of the Court as a whole and of individual justices.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

Get analyses of legal data at Optimized Legal

25 Comments Add yours