In the introduction to the eye opening work on the Supreme Court certiorari process Deciding to Decide, author H.W. Perry summarizes the Court’s lack of institutional transparency. Perry wrote, “Although some rules are published, most of the internal procedures are by consensus, are unpublished, and are frequently unknown” (p. 17). Perry goes on, “We on the outside find out about them only when a justice happens to mention them in a speech or article.” This lack of transparency was what made the release of Justice Blackmun’s papers so powerful. Granted, few justices likely grade oral arguments in the same manner as Justice Blackmun did, but both unique processes to individual justices and processes dispersed across justices are interesting to learn about for their own sake. These processes also tell us more about the decision making process than we knew prior. Nonetheless, much is still unknown about how the justices, with the help of their clerks, reach their decisions.

The focus of this post is uncovering the sources that the justices rely on in their decisions. One way to do this could be through interviews if the justices and clerks were willing to divulge this information. In the absence of such direct sources, indirect methods also help to shed light on the Court’s internal processes. In one paper, for instance, I found that the Court shares more language with parties’ merits briefs than it does with amicus briefs or lower court opinions after controlling for shared language between all three sources. This hints at the possibility that the justices use parties’ briefs as roadmaps in ways that they don’t with other sources.

This post looks to the justices’ overt citations to briefs as a direct way to ascertain a brief’s importance to a case. Although the justices’ opinions often cite to parties’ merits briefs in cases, cites to amicus briefs are rarer. There are several reasons for this. Many cases have large numbers of amicus briefs that crowd out the impact of individual briefs. Amicus briefs also tend to focus on discreet policy issues in cases and so may hit on issues that are outside of the justices’ focuses.

A unique approach employed in this post is to use several levels of controls to try to suss out a weak causal process in the justices’ citations. To do this this post uses the 2018 Term cases with signed opinion(s) and more than five amicus briefs filed on the merits. It then looks at cites to sources other than Supreme Court opinions since 1900 (so pre-1900 cases are included as are citations to cases from lower courts). The point of focusing on these sources was to isolate potentially unique resources. It also looks to citations to journals, state statutes, and other less frequently utilized resources. These citations were uncovered by using opinions that contained hyperlinked sources so that the hyperlinks could be isolated. These sources were then used as search terms across all of the briefs within a case. If a source was cited in only one brief or in one party’s brief and one amicus brief it was retained as a source of interest. The weak causal argument is that due to the unique nature of the cite and the minimal sources alluding to the cite, the source or sources from the brief were likely what led the justice(s) and/or clerk(s) to the cite. This in turn helps with the inference that this brief could have been an important resource for the justice when drawing up a given opinion.

Citations

Direct citations to briefs are a clear resource for understanding opinion construction. With these, the justices give us glimpses of the resources that helped them render their decisions. Citations are not always positive though. Sometimes justices use them as foils or straw men to breakdown a counterargument. In such instances they cite a source in order to deconstruct an argument and with the intention of solidifying their point against critiques. In such instances though, the justices still give us a sense of which arguments they deemed sufficiently important enough to respond to, and who made those arguments. Even though in such instances the justices do not agree with that argument, they acknowledge the argument’s power as well as the importance of the brief that made it. This in turn gives the brief added justification if only for the purpose of telling us that it contained an argument that impacted a justice either positively or negatively. Such processes are also apparent in the weak causal cases where the justices do not mention the initial citing source, but these processes are more direct in cases where the justices cite the briefs directly.

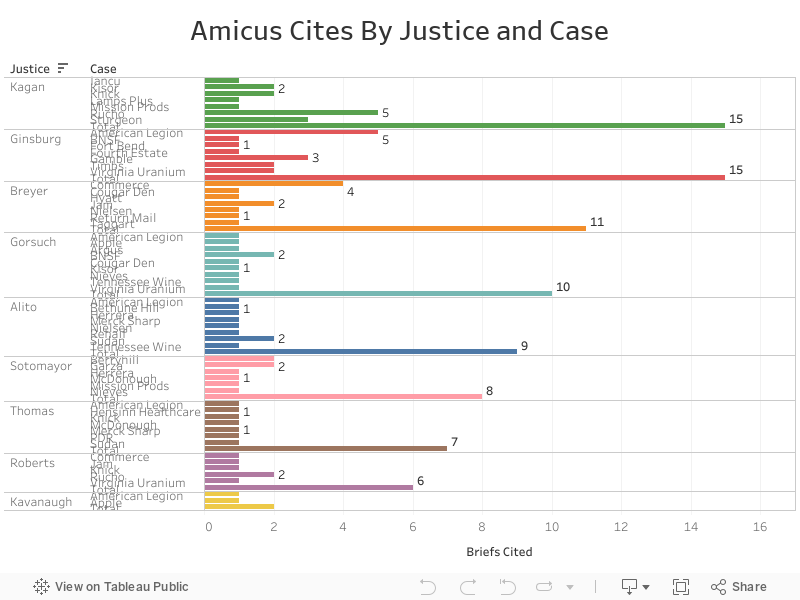

The figure below has all of the justices cites to amicus briefs for the 2018 Term broken down by case. It counts each brief cited in a case by a justice as one so multiple cites to the same brief are not double counted. It also has the total number of citations for each justice across the term within each justice’s frame and below the names of the cases.

Here we see that the more liberal justices were more active citers of amicus briefs during the 2018 Term. Justices Kagan and Ginsburg both had 15 case/cites, while Breyer came next with 11. The bulk of Kagan’s cites were from Rucho v. Common Cause while Ginsburg’s were in American Legion. Breyer’s opinion with the his most cites was in Department of Commerce v. New York.

Justices Gorsuch, Alito, Sotomayor, Thomas, and Roberts all had between ten and six cites to amicus briefs across the term. Justice Kavanaugh in his first term on the Court had by far the fewest with only one in American Legion and one in Apple v. Pepper.

Sources Behind the Sources

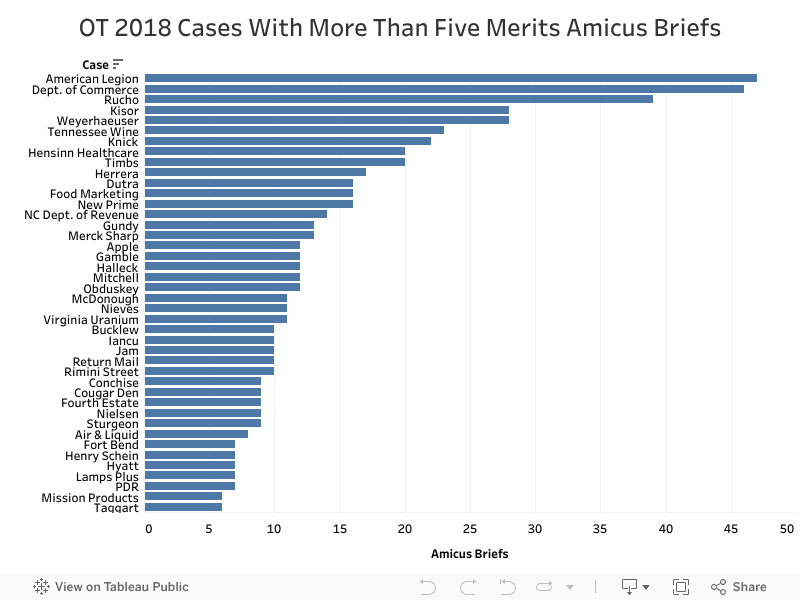

The next set of figures examine the briefs which cited more esoteric sources that were also included in the justices’ opinions. This begins by paring down the set of cases from OT 2018 with more than five merits amicus briefs and a signed opinion.

The three cases with more merits amicus briefs than all others were American Legion, Department of Commerce v. New York, and Rucho v. Common Cause. The cases with the most merits amicus filings for the 2018 Term had far fewer amicus briefs than we’ve seen in cases in past years like in Obergefell v. Hodges which had over 100 merits amicus briefs. The number of cases with at least six amicus briefs, however, gives quite a few cases for this analysis. The opinions in these cases led to almost 180 unique cites for the overall dataset.

First, breaking this down by justice and opinion type we see that significant variation in the number of these cites by justice. Within each colored bar, the top number is the percentage of the cites by opinion type for each justice and the bottom number is the corresponding count of such cites by opinion type and justice.

Unlike the direct cites to the briefs, Gorsuch and Alito are far ahead of the rest of the pack of justices in their unique cites. Gorsuch’s 77 such cites are more than twice as many as those from any other justice. Gorsuch also has a decent mix of these cites across opinion type. Alito’s balance is weighted towards majority opinions, while Ginsburg’s is weighted towards dissents. The only justice with only one opinion type is Roberts who only had such unique cites in his majority opinions. Roberts, however, is an infrequent dissent author and an even less frequent concurrence author. Kavanaugh had more unique cites in this manner than both Justices Sotomayor and Breyer.

The next figure looks at this data by case and justice. The legend on the right conveys the bar color for each individual justice. The number within each bar is the number of cites by justice for that decision.

Examples of these unique cites from amicus briefs in Gamble that were also cited in the justices’ opinions include Harlan v. People, 1 Doug. 207 (Mich. 1843), Commonwealth v. Fuller, 49 Mass. 313 (1844), and State v. Antonio, 2 Tread. 776 (1816).

Gamble and New Prime were the cases with the most unique cites. The cites in Gamble were from a mix of Justices Gorsuch, Ginsburg, and Alito’s opinions. The ones in New Prime were solely from Justice Gorsuch. Other cases with a high number of unique cites include Nielsen v. Preap, Kisor v. Wilke, and Tennessee Wine. All opinions with a large number of such cites aside from New Prime have cites from more than one justice’s opinion. The next case with only one justice’s cites is Gundy where all ten unique cites come from Justice Gorsuch’s dissenting opinion.

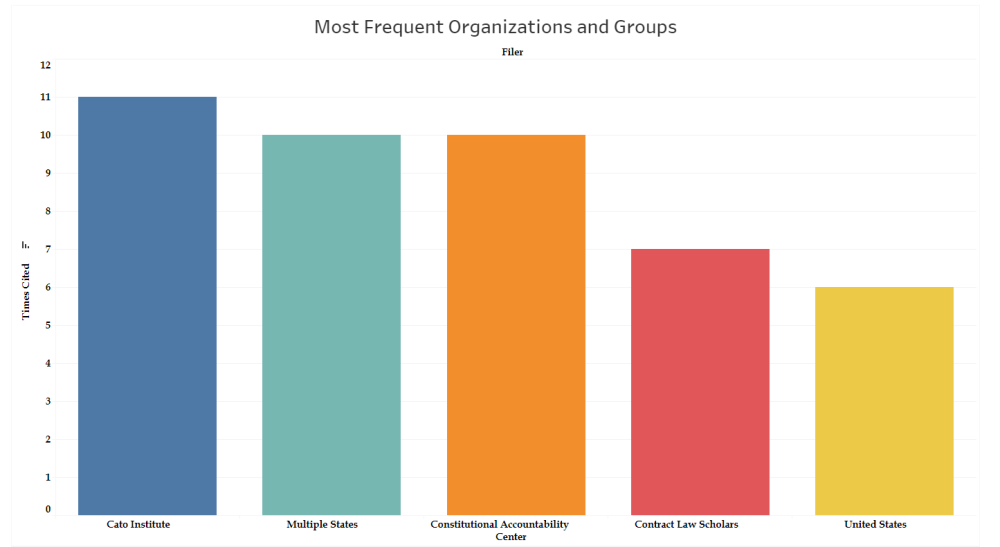

Looking at the groups with these cites we see a few groups and types played the most prominent initial citer role.

The Cato Institute led the way for the 2018 Term with 11 unique cites picked up by the justices. This was followed by cites found in amicus briefs signed by multiple states as well as those from the Constitutional Accountability Center which each were responsible for ten unique cites. Contract Law Scholars in Lamps Plus conveyed seven unique cites and these scholars are followed by the United States which was responsible for six unique cites across its amicus briefs for the 2018 term.

Seven of the Cato Institute’s cites and the Constitutional Accountability’s cites came from their co-authored brief in Gamble. Four of the shared cites were in Justice Gorsuch’s dissenting opinion, two were in Justice Alito’s majority opinion, and one was in Justice Ginsburg’s dissenting opinion. Gorsuch had several other unique shared cites with briefs from the Cato Institute with one in his majority opinion in New Prime, another in his concurrence in Kisor v. Wilke, and one from his dissent in Gundy. The other two shared unique cites for the Cato Institute were from Justice Alito’s majority opinion in Tennessee Wine. The additional three shared unique cites for the Constitutional Accountability Center were found in Justice Gorsuch’s majority opinion in New Prime.

In addition to the organizations whose unique sources were cited most frequently, other prominent briefs types made contributions to the justices’ cites. Two Senators, Whitehouse and Hatch, both had briefs with unique cites picked up by the justices for instance. Interestingly, Senator Hatch’s shared cite was with Justice Ginsburg’s dissenting opinion in Gamble, while Senator Whitehouse’s cite was shared with Justice Gorsuch’s majority opinion in New Prime. The other brief from congressional representatives that shared unique cites with an opinion was from Representatives Andy Biggs et al. in Nielsen v. Preap. Justice Thomas’ concurrence, Breyer’s dissent, and Alito’s majority opinion all shared a unique cite with the representatives’ brief.

While these methods will not tell us the justices’ resources in constructing opinions with absolute certainty, they do give us some additional insight into the justices’ processes of developing arguments in their opinions. They also tell us with a greater degree of certainty, which briefs played a role in their decision making. This in turn might in turn highlight the importance of specific groups’ briefs for specific justices and in specific cases. Additional work in this area could potentially better direct resources (and could be instructive on when to deploy resources to begin with) in order to make a greater impact on specific aspects of the Court’s decisions.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

2 Comments Add yours