Yesterday the Supreme Court heard the long-awaited oral arguments in cases that may overturn the right to affirmative action in higher education. Some states like Michigan already banned action through popular vote. For states that still allow it though the question of constitutionality is on the Court’s agenda.

In Grutter v. Bollinger, decided in 2003, Justice O’Connor wrote, “We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary to further the interest [in student body diversity] approved today.” This wasn’t an exact timetable but expressed a hope that this policy would no longer be necessary within a certain window. This window, however, was uncertain and so affirmative action could come to a close before or after that date which will come to pass in 2028.

So far in oral arguments this term the justices have shown themselves to likely be a little more transparent about their anticipated positions on the merits in cases. In these cases, the going expectation is that the liberal justices will vote against the petitioner’s argument which was in favor of overturning the constitutionality of affirmative action. Correspondingly the conservative justices are expected to vote against the attorneys on the respondents’ side arguing in favor of retaining some vestige of affirmative action in higher education.

Justice Thomas who is expected to vote to overturn the affirmative action policies said, for instance, “I’ve heard the word ‘diversity’ quite a few times, and I don’t have a clue what it means.” Justice Jackson on the other end of the ideological spectrum said, “What I think you’re saying is that people have to mask their identities when they come into contact with the admissions office just on the basis of their difference.” Along similar lines to Justice Jackson, Justice Kagan said, “The race is part of the culture and the culture is part of the race, isn’t it? I mean, that’s slicing the baloney awfully thin.”

This term Justice Jackson has been turning heads with her dedicated participation in oral arguments. Not only was she the lead speaker in terms of word count in seven of the Court’s first eight arguments, but she spoke more than any other current justice or her predecessor Justice Breyer in each of their first eight oral arguments on the Court.

Words alone are not going to define case outcomes though. This may be no more apparent than in the Students for Fair Admissions cases. Justice Jackson only participated in the UNC arguments. She recused herself from the Harvard case due to her prior participation as a member of the Harvard Board of Overseers and so there are only eight voting justices for that case.

Words may shape the case narratives though. Jackson for instance not only asked questions but also expressed views on case-related matter. In one instance she said, “There are 40 factors about all sorts of things that the admissions office is looking at. And you haven’t demonstrated or shown one situation in which all they look at is race and take from that stereotypes and other things. They’re looking at the full person with all of these characteristics.”

On the other side of the ideological divide, Justice Barrett explained to respondent’s attorney Ryan Park, “This Court’s precedents, I mean, Grutter also says — sorry, let me put my readers on here — you know, using racial classifications are so potentially dangerous, however compelling their goals, they can be employed no more broadly. Going down a little bit further, all governmental use of race must have a logical end point, reasonable durational limits, sunset provisions, and race-conscious admissions policies.” Statements rather than questions help shape the contours of the discussion without seeking particular responses from the attorneys or by asking questions where the answer is clear and in favor of the party presenting the argument.

How did the justices’ speech counts compare to one another? When Justice Jackson participated, she was by far the leading speaker. Below is a graph of the overall justices’ words spoken in the UNC case.

Justice Jackson spoke over 1,000 words more than the next most active justice – Justice Sotomayor. The three liberal justices spoke the more than any of the conservative justices in this case and notably, the four female justices were the most active speakers in the arguments in this case.

Without Justice Jackson’s involvement, the word counts in the Harvard case looked quite different. Below is a graph of those word counts.

Justice Kavanaugh was the most active speaker in the Harvard arguments followed by Justices Kagan and Sotomayor. In the Harvard arguments no justice approached the word count totals for Justices Jackson or Sotomayor from the UNC arguments.

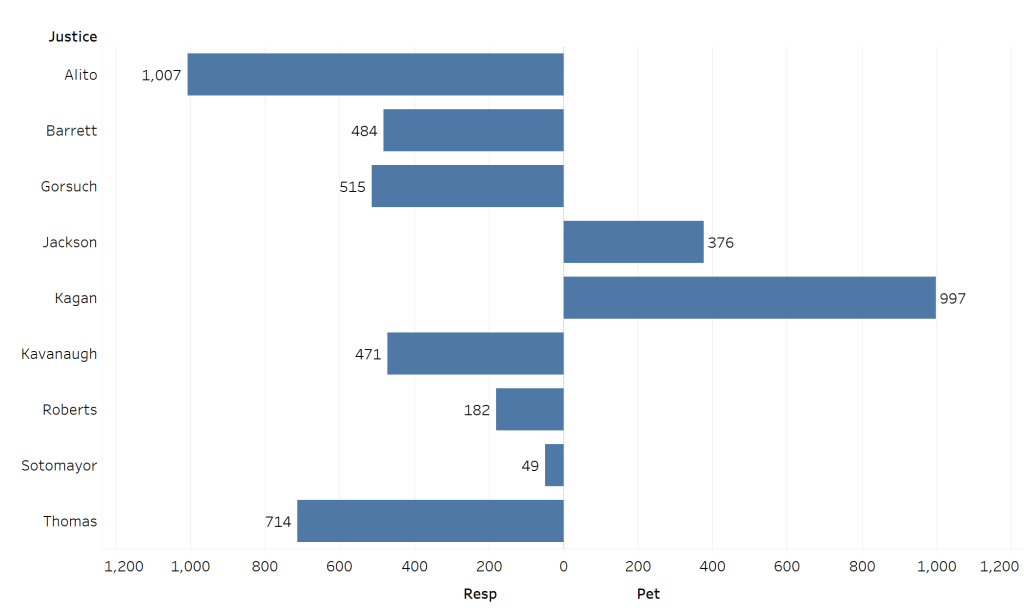

When the word counts are totaled from the two arguments the picture tells a few different stories.

First, in only one argument, Justice Jackson’s word count total was only 23 words behind Justice Sotomayor’s total from both arguments which is the highest count for any of the justices in these cases. Looking comparatively, Justice Roberts spoke just more than half as much as either Sotomayor or Jackson.

The three more liberal justices were the leading speakers in the combination of arguments. Knowing Justice Breyer’s propensity for prolonged speech, he presumably would be near the top of the graph if he was still a member of the Court. The juxtaposition of the liberals leading the speech counts while likely being on the dissenting side of the votes (and knowing this) hints at the possibility that the liberals used oral arguments to convey their perceived upsides to affirmative action policies in a manner separate from a dissenting opinion.

The justices likely votes in these cases can also be assumed based on their choices of when to speak. Scholarship in this area shows the justices’ propensities to speak more during the argument of the party they will vote against on the merits. In this case almost all the justices lined up in this manner with clear distinctions in how much they spoke to the different attorneys.

Justice Sotomayor is the only justice on the opposite end of word counts from the side where she can be expected to vote on the merits, and the 49-word distinction is close enough to zero that it is likely negligible. The rest of the justices’ differential word counts are not close to zero and line up as expected.

Although historically the justices word choices are not great predictors of how they will vote, the justices do not appear to be hiding the ball in these cases. Combined with word count data and the bulk of expectations of their votes based on prior affirmative action decisions, these arguments presented a picture of a strong likelihood that the justices will not surprise anyone by shutting down affirmative action policies in most if not all institutions of higher education.

On Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

On LinkedIn here

7 Comments Add yours