This is the first of a series of two posts examining the federal government’s litigation in the Supreme Court. While this post looks at the last several terms of government litigation, the next will analyze the government’s upcoming cases.

The federal government, through the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG), is the most frequent participant participating entity before the Supreme Court. According to the Solicitor General’s website, the OSG has filed merits briefs in 99 cases since the 2012 Supreme Court term. Many scholarly works have been dedicated to understanding the OSG’s relationship to the Supreme Court while others focus on the OSG’s success. As a book on the subject by Professors Ryan Black and Ryan Owens assesses,

“Put simply, regardless of the stage of decision making or measurement used to examine OSG success, the findings are clear. The SG and his or her office are highly successful. Whether success comes in the form of getting the Court to hear a case (or decline to hear it) or to find for the government on the merits, the office’s success is beyond all others.” (p. 27)

Based on the available evidence it may be somewhat surprising that since this book was released in 2012, the OSG has not been the paragon of success before the Court that it is and was often assumed to be.

This post utilizes data from the Supreme Court Database and takes a look at the OSG’s performance before the Court in merits cases since 2012 from several dimensions. In doing, so it points out some lesser known details of regarding judicial behavior in such cases. The three levels of analysis in this post are government success, the justices, and the cases.

Government Success

The OSG participated in more cases on the merits in 2012 than in any subsequent term. The case counts breakdown as follows:

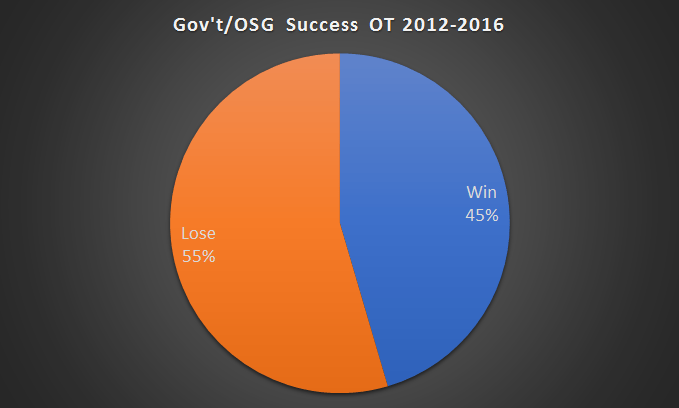

These sum to 99 cases, and of these cases the OSG has less than a 50% success rate.

These statistics make President Trump’s staking important agenda items such as the travel ban on Supreme Court resolution appear risky. They also help to further explain Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s as well as President Trump’s strong rhetoric regarding the importance of the Supreme Court and of nominating individuals to the Court that will uphold conservative measures.

When the government tries cases before the Supreme Court, its likelihood of success is somewhat dependent on which justice authors the majority opinion. The government has been least successful when the most frequent author of such decisions is the opinion author.

In cases involving an OSG merits brief and authored by Chief Justice Roberts since 2012, the government lost fifteen of sixteen decisions. Losses include high profile cases such as Shelby County v. Holder as well as lesser known decisions. This may be an ominous sign for important future government decisions as the Court has ruled against both democrat (under Obama) and republican (under Trump) agenda items. On the other end of the spectrum, the government has been most successful when Justice Ginsburg is the majority opinion author.

Another way to parse the cases is by the main issue area. Breaking down the government’s success by issue (when a case had a discrete issue that fell into one of these categories) looks like the following:

The most cases came from the criminal procedure area where the government won one more case than it lost. The government lost more cases than it won in several areas, with its worst performance in First Amendment cases. It also lost more cases than it won in the second most frequent issue area: economic activity.

By the Justices

As with Chief Justice Roberts’ votes in cases involving the OSG, the justices in general display mixed and sometimes unpredictable behavior when the OSG litigates a case. Looking at the justices’ votes for and against the government’s positions in these cases Chief Justice Roberts has also voted against the government’s positions more frequently than any of the other justices.

Justice Thomas was the OSG’s strongest proponent in these cases splitting his votes for and against the government. Most of the justices’ proportions of votes were weighted a bit more heavily towards against government than for government. Interestingly, this is the same both for the more liberal and conservative justices.

Another characteristic that many of the justices shared was frequency in the majority in these cases. These frequencies look like:

Justice Kennedy was consistently in the majority in these cases just as he is for the vast majority of cases the Court hears. The Court’s more conservative wing – Justices Thomas, Scalia (when on the Court), and Alito were most frequently in the dissenting coalitions in these cases.

This held true for written dissents as well.

Justices Thomas and Alito both wrote eleven dissents in this set of cases which is more than any other justice. Justice Sotomayor came in next with eight written dissents, followed closely by Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Scalia. Since Justice Scalia was not on the Court for the second half of the 2015 term or any of the 2016 term, his seven dissents make up a higher fraction of his total cases than for any other justice aside from Gorsuch (who has no written dissents in these cases).

Justices and Cases

Focusing on the case level fills in some of the gaps in information surrounding these decisions. These cases dealt with a variety of issues and used an assortment of tools to resolve them. The bulk of the decisions involved interpreting a statute, oftentimes focusing on whether the statute was consistent with the Constitution. The justices’ share of statutory construction cases from this set looks like:

Of the justices, Chief Justice Roberts authored the most of these decisions. Justices Sotomayor, Ginsburg, and Kagan were not far behind Chief Justice Roberts in this respect while Justices Kennedy and Alito authored the least of these decisions (aside from Justice Gorsuch).

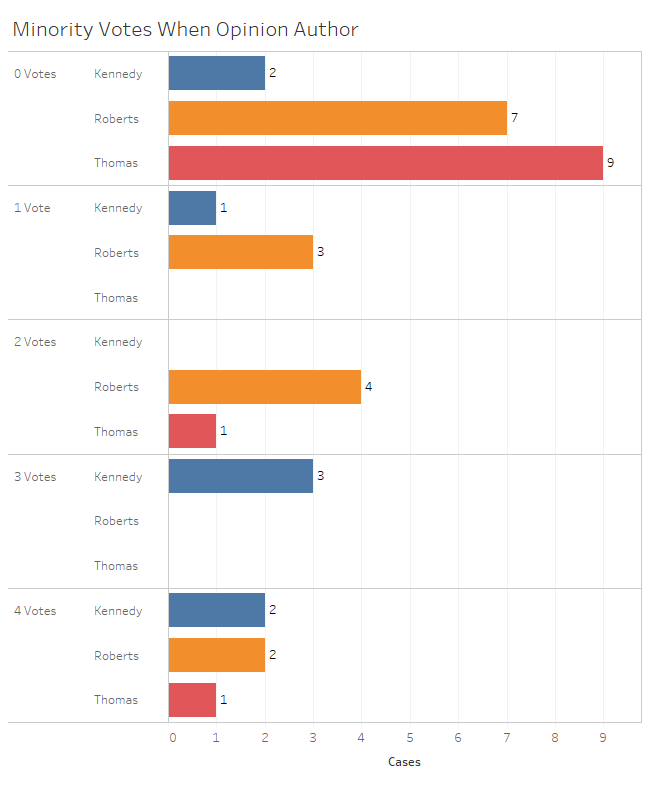

We can also break down the justices’ support for their fellow justices’ decisions by looking at minority / dissenting vote counts against decisions they authored. The next figure looks at these counts for three justices in particular: Justices Thomas, Kennedy, and Roberts:

Justice Thomas had the most unanimous support of the three justices. This accords with commentary surrounding Justice Thomas that often points out he is typically assigned less contentious and noteworthy cases than other justices. Justices Kennedy and Roberts both authored two such decisions with a maximum of possible dissenting votes of four. Justice Kennedy also authored three decisions with three minority votes. Here we see, as is often the case, Justice Kennedy authored multiple majority opinions in this set that divided the justices.

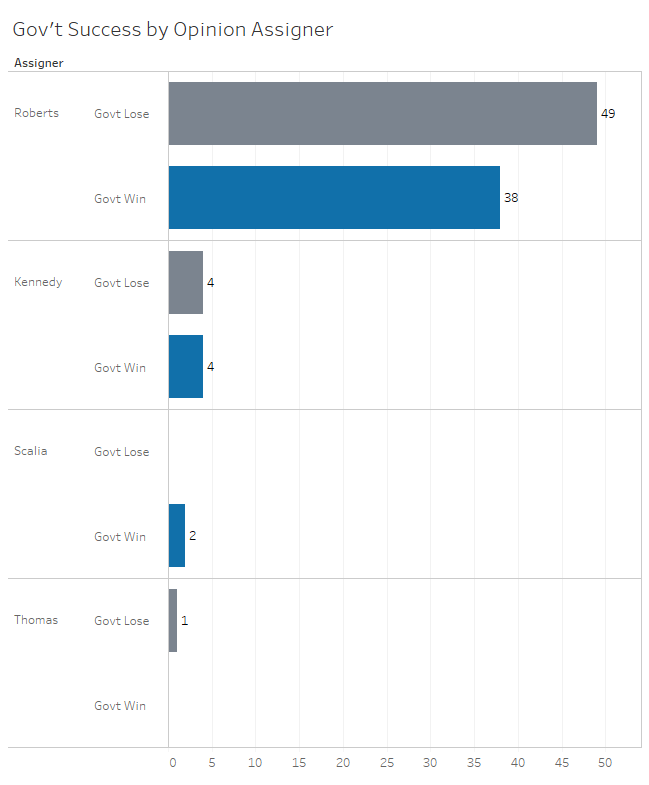

Who was assigning these cases? Chief Justice Roberts does so whenever he is in the majority. If he is not, then the task falls to the senior justice in the majority. In this set of cases, these have included justices Kennedy, Scalia, and Thomas.

This figure adds up to 98 cases as the 99th, United States v. Texas, divide the justices equally, and thus was summarily affirmed with no majority opinion author. While the government was successful in both opinions assigned by Justice Scalia (one to himself and one to Justice Kagan). The government lost the only such case assigned by Justice Thomas though, Alleyne v. United States, which he assigned to himself.

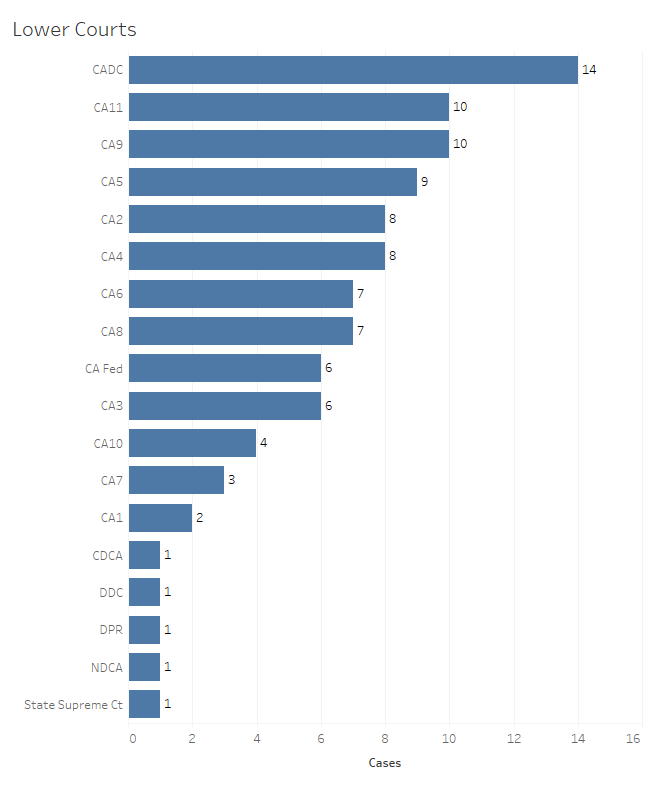

A final way to examine these cases is by looking at the court that heard the case before the Supreme Court. The following figure breaks the decisions down by the lower court.

Although more cases come from the Ninth Circuit than from any other lower court, the bulk of these cases come from the D.C. Circuit. This is logical, though, since many of the government’s cases arise in the District of Columbia. The Ninth Circuit is tied with the Eleventh Circuit for the second most cases in this set. Of the federal appeals circuits, the fewest such cases came from the First and Seventh Circuits. Cases also came to the Supreme Court from several district courts (these are often election/voting related cases).

In this era where political leaders are looking more and more to the Supreme Court to decide on policy matters, and where the Court is looking increasingly willing to do so, the Court’s decisions in cases involving the federal government are increasingly important. The government’s reliance on the Court for the success of its own agenda, however, has never seemed more questionable. This may become less so if President Trump has the opportunity to appoint another justice in place of Justices Kennedy or Ginsburg.

The Court is scheduled to hear the travel ban case on Tuesday, October 10 with many other decisions with far reaching policy implications coming before and after. These cases will test the Court’s support for the government and the government’s positions in novel ways. They will also most likely enhance the reach of the Court into areas it has yet to engage.

For more empirical commentary on the Supreme Court follow on Twitter: @AdamSFeldman

8 Comments Add yours